Category Archives: Model Thinking

The CFO as Chief Option Architect: Embracing Uncertainty

Part I: Embracing the Options Mindset

This first half explores the philosophical and practical foundation of real options thinking, scenario-based planning, and the CFO’s evolving role in navigating complexity. The voice is grounded in experience, built on systems thinking, and infused with a deep respect for the unpredictability of business life.

I learned early that finance, for all its formulas and rigor, rarely rewards control. In one of my earliest roles, I designed a seemingly watertight budget, complete with perfectly reconciled assumptions and cash flow projections. The spreadsheet sang. The market didn’t. A key customer delayed a renewal. A regulatory shift in a foreign jurisdiction quietly unraveled a tax credit. In just six weeks, our pristine model looked obsolete. I still remember staring at the same Excel sheet and realizing that the budget was not a map, but a photograph, already out of date. That moment shaped much of how I came to see my role as a CFO. Not as controller-in-chief, but as architect of adaptive choices.

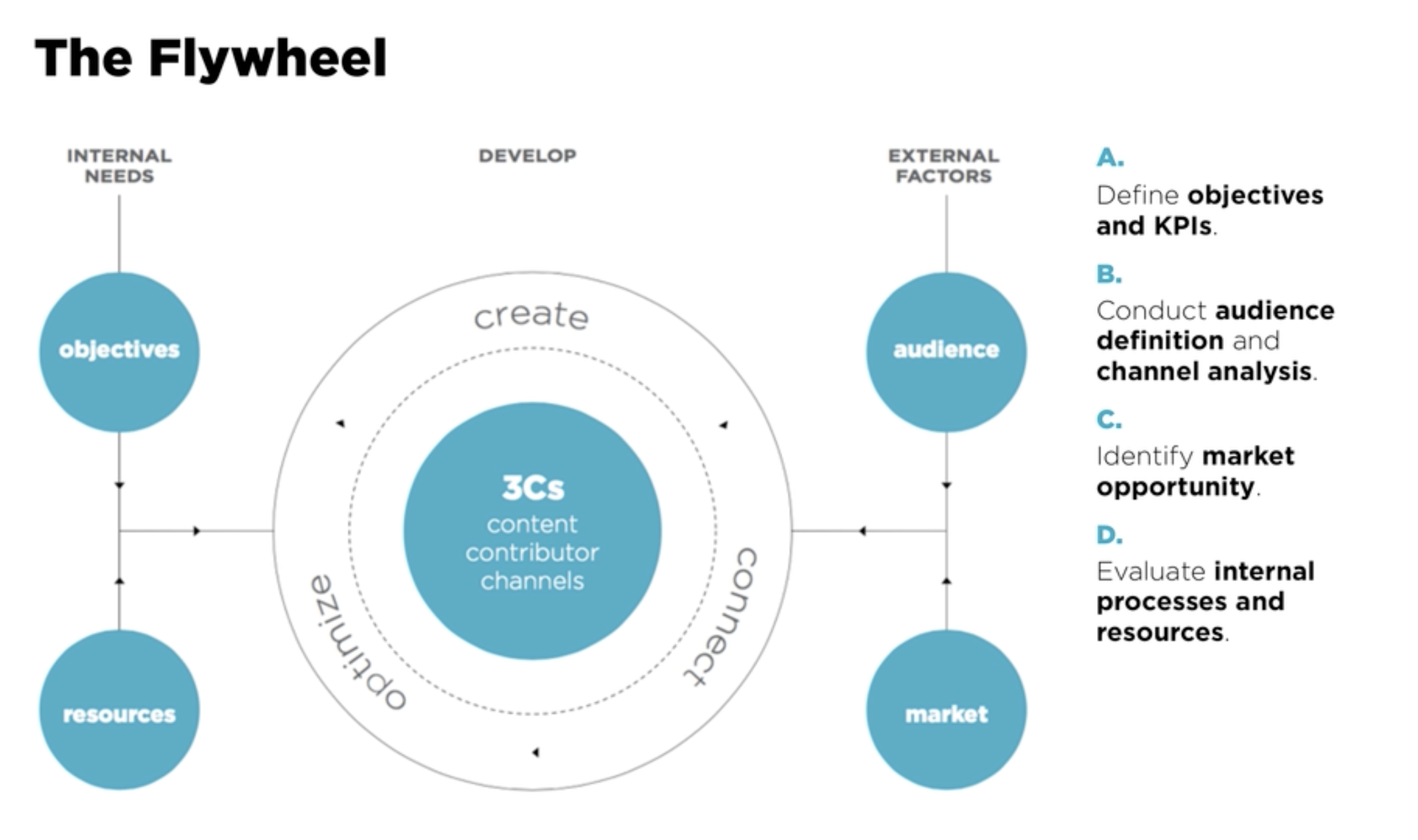

The world has only become more uncertain since. Revenue operations now sit squarely in the storm path of volatility. Between shifting buying cycles, hybrid GTM models, and global macro noise, what used to be predictable has become probabilistic. Forecasting a quarter now feels less like plotting points on a trendline and more like tracing potential paths through fog. It is in this context that I began adopting and later, championing, the role of the CFO as “Chief Option Architect.” Because when prediction fails, design must take over.

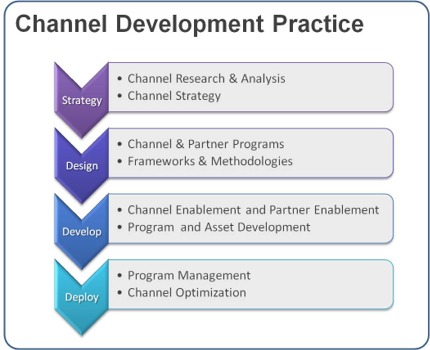

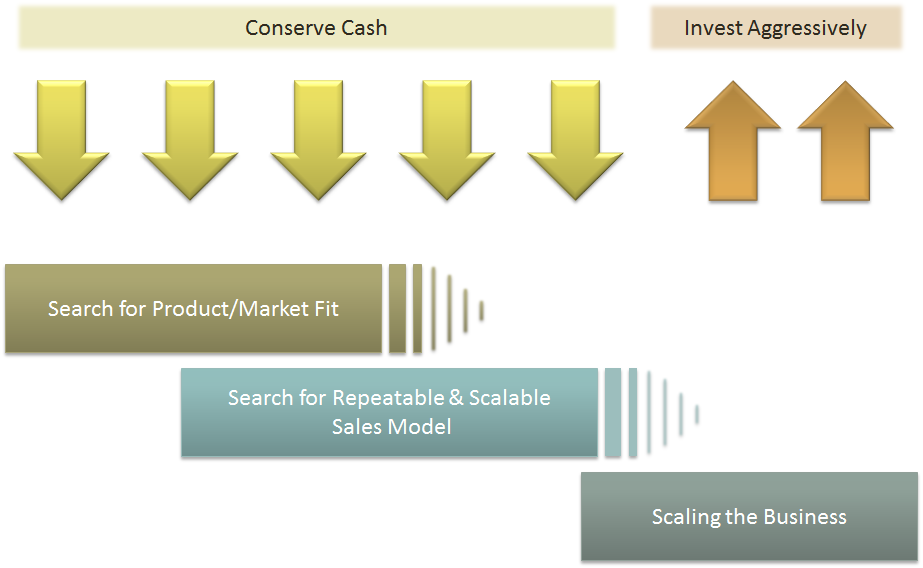

This mindset draws deeply from systems thinking. In complex systems, what matters is not control, but structure. A system that adapts will outperform one that resists. And the best way to structure flexibility, I have found, is through the lens of real options. Borrowed from financial theory, real options describe the value of maintaining flexibility under uncertainty. Instead of forcing an all-in decision today, you make a series of smaller decisions, each one preserving the right, but not the obligation, to act in a future state. This concept, though rooted in asset pricing, holds powerful relevance for how we run companies.

When I began modeling capital deployment for new GTM motions, I stopped thinking in terms of “budget now, or not at all.” Instead, I started building scenario trees. Each branch represented a choice: deploy full headcount at launch or split into a two-phase pilot with a learning checkpoint. Invest in a new product SKU with full marketing spend, or wait for usage threshold signals to pass before escalation. These decision trees capture something that most budgets never do—the reality of the paths not taken, the contingencies we rarely discuss. And most importantly, they made us better at allocating not just capital, but attention. I am sharing my Bible on this topic, which was referred to me by Dr. Alexander Cassuto at Cal State Hayward in the Econometrics course. It was definitely more pleasant and easier to read than Jiang’s book on Econometrics.

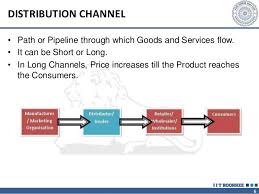

This change in framing altered my approach to every part of revenue operations. Take, for instance, the deal desk. In traditional settings, deal desk is a compliance checkpoint where pricing, terms, and margin constraints are reviewed. But when viewed through an options lens, the deal desk becomes a staging ground for strategic bets. A deeply discounted deal might seem reckless on paper, but if structured with expansion clauses, usage gates, or future upsell options, it can behave like a call option on account growth. The key is to recognize and price the option value. Once I began modeling deals this way, I found we were saying “yes” more often, and with far better clarity on risk.

Data analytics became essential here not for forecasting the exact outcome, but for simulating plausible ones. I leaned heavily on regression modeling, time-series decomposition, and agent-based simulation. We used R to create time-based churn scenarios across customer cohorts. We used Arena to simulate resource allocation under delayed expansion assumptions. These were not predictions. They were controlled chaos exercises, designed to show what could happen, not what would. But the power of this was not just in the results, but it was in the mindset it built. We stopped asking, “What will happen?” and started asking, “What could we do if it does?”

From these simulations, we developed internal thresholds to trigger further investment. For example, if three out of five expansion triggers were fired, such as usage spike, NPS improvement, and additional department adoption, then we would greenlight phase two of GTM spend. That logic replaced endless debate with a predefined structure. It also gave our board more confidence. Rather than asking them to bless a single future, we offered a roadmap of choices, each with its own decision gates. They didn’t need to believe our base case. They only needed to believe we had options.

Yet, as elegant as these models were, the most difficult challenge remained human. People, understandably, want certainty. They want confidence in forecasts, commitment to plans, and clarity in messaging. I had to coach my team and myself to get comfortable with the discomfort of ambiguity. I invoked the concept of bounded rationality from decision science: we make the best decisions we can with the information available to us, within the time allotted. There is no perfect foresight. There is only better framing.

This is where the law of unintended consequences makes its entrance. In traditional finance functions, overplanning often leads to rigidity. You commit to hiring plans that no longer make sense three months in. You promise CAC thresholds that collapse under macro pressure. You bake linearity into a market that moves in waves. When this happens, companies double down, pushing harder against the wrong wall. But when you think in options, you pull back when the signal tells you to. You course-correct. You adapt. And paradoxically, you appear more stable.

As we embedded this thinking deeper into our revenue operations, we also became more cross-functional. Sales began to understand the value of deferring certain go-to-market investments until usage signals validated demand. Product began to view feature development as portfolio choices: some high-risk, high-return, others safer but with less upside. Customer Success began surfacing renewal and expansion probabilities not as binary yes/no forecasts, but as weighted signals on a decision curve. The shared vocabulary of real options gave us a language for navigating ambiguity together.

We also brought this into our capital allocation rhythm. Instead of annual budget cycles, we moved to rolling forecasts with embedded thresholds. If churn stayed below 8% and expansion held steady, we would greenlight an additional five SDRs. If product-led growth signals in EMEA hit critical mass, we’d fund a localized support pod. These weren’t whims. They were contingent commitments, bound by logic, not inertia. And that changed everything.

The results were not perfect. We made wrong bets. Some options expired worthless. Others took longer to mature than we expected. But overall, we made faster decisions with greater alignment. We used our capital more efficiently. And most of all, we built a culture that didn’t flinch at uncertainty—but designed for it.

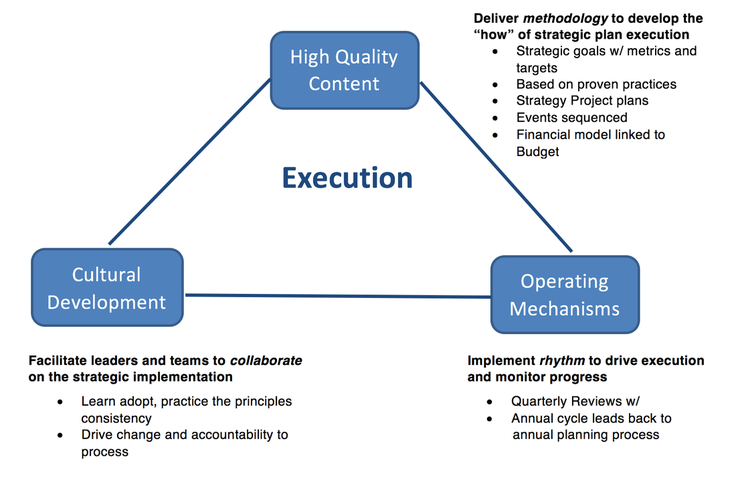

In the next part of this essay, I will go deeper into the mechanics of implementing this philosophy across the deal desk, QTC architecture, and pipeline forecasting. I will also show how to build dashboards that visualize decision trees and option paths, and how to teach your teams to reason probabilistically without losing speed. Because in a world where volatility is the only certainty, the CFO’s most enduring edge is not control, but it is optionality, structured by design and deployed with discipline.

Part II: Implementing Option Architecture Inside RevOps

A CFO cannot simply preach agility from a whiteboard. To embed optionality into the operational fabric of a company, the theory must show up in tools, in dashboards, in planning cadences, and in the daily decisions made by deal desks, revenue teams, and systems owners. I have found that fundamental transformation comes not from frameworks, but from friction—the friction of trying to make the idea work across functions, under pressure, and at scale. That’s where option thinking proves its worth.

We began by reimagining the deal desk, not as a compliance stop but as a structured betting table. In conventional models, deal desks enforce pricing integrity, review payment terms, and ensure T’s and C’s fall within approved tolerances. That’s necessary, but not sufficient. In uncertain environments—where customer buying behavior, competitive pressure, or adoption curves wobble without warning: rigid deal policies become brittle. The opportunity lies in recasting the deal desk as a decision node within a larger options tree.

Consider a SaaS enterprise deal involving land-and-expand potential. A rigid model forces either full commitment upfront or defers expansion, hoping for a vague “later.” But if we treat the deal like a compound call option, we see more apparent logic. You price the initial land deal aggressively, with usage-based triggers that, when met, unlock favorable expansion terms. You embed a re-pricing clause if usage crosses a defined threshold in 90 days. You insert a “soft commit” expansion clause tied to the active user count. None of these is just a term. They are embedded with real options. And when structured well, they deliver upside without requiring the customer to commit to uncertain future needs.

In practice, this approach meant reworking CPQ systems, retraining legal, and coaching reps to frame options credibly. We designed templates with optionality clauses already coded into Salesforce workflows. Once an account crossed a pre-defined trigger say, 80% license utilization, then the next best action flowed to the account executive and customer success manager. The logic wasn’t linear. It was branching. We visualized deal paths in a way that corresponds to mapping a decision tree in a risk-adjusted capital model.

Yet even the most elegant structure can fail if the operating rhythm stays linear. That is why we transitioned away from rigid quarterly forecasts toward rolling scenario-based planning. Forecasting ceased to be a spreadsheet contest. Instead, we evaluated forecast bands, not point estimates. If base churn exceeded X% in a specific cohort, how did that impact our expansion coverage ratio? If deal velocity in EMEA slowed by two weeks, how would that compress the bookings-to-billings gap? We visualized these as cascading outcomes, not just isolated misses.

To build this capability, we used what I came to call “option dashboards.” These were layered, interactive models with inputs tied to a live pipeline and post-sale telemetry. Each card on the dashboard represented a decision node—an inflection point. Would we deploy more headcount into SMB if the average CAC-to-LTV fell below 3:1? Would we pause feature rollout in one region to redirect support toward a segment with stronger usage signals? Each choice was pre-wired with boundary logic. The decisions didn’t live in a drawer—they lived in motion.

Building these dashboards required investment. But more than tools, it required permission. Teams needed to know they could act on signal, not wait for executive validation every time a deviation emerged. We institutionalized the language of “early signal actionability.” If revenue leaders spotted a decline in renewal health across a cluster of customers tied to the same integration module, they didn’t wait for a churn event. They pulled forward roadmap fixes. That wasn’t just good customer service, but it was real options in flight.

This also brought a new flavor to our capital allocation rhythm. Rather than annual planning cycles that locked resources into static swim lanes, we adopted gated resourcing tied to defined thresholds. Our FP&A team built simulation models in Python and R, forecasting the expected value of a resourcing move based on scenario weightings. For example, if a new vertical showed a 60% likelihood of crossing a 10-deal threshold by mid-Q3, we pre-approved GTM spend to activate contingent on hitting that signal. This looked cautious to some. But in reality, it was aggressive and in the right direction, at the right moment.

Throughout all of this, I kept returning to a central truth: uncertainty punishes rigidity, but rewards those who respect its contours. A pricing policy that cannot flex will leave margin on the table or kill deals in flight. A hiring plan that commits too early will choke working capital. And a CFO who waits for clarity before making bets will find they arrive too late. In decision theory, we often talk about “the cost of delay” versus “the cost of error.” A good options model minimizes both, which, interestingly, is not by being just right, but by being ready.

Of course, optionality without discipline can devolve into indecision. We embedded guardrails. We defined thresholds that made decision inertia unacceptable. If a cohort’s NRR dropped for three consecutive months and win-back campaigns failed, we sunsetted that motion. If a beta feature was unable to hit usage velocity within a quarter, we reallocated the development budget. These were not emotional decisions, but they were logical conclusions of failed options. And we celebrated them. A failed option, tested and closed, beats a zombie investment every time.

We also revised our communication with the board. Instead of defending fixed forecasts, we presented probability-weighted trees. “If churn holds, and expansion triggers fire, we’ll beat target by X.” “If macro shifts pull SMB renewals down by 5%, we stay within plan by flexing mid-market initiatives.” This shifted the conversation from finger-pointing to scenario readiness. Investors liked it. More importantly, so did the executive team. We could disagree on base assumptions but still align on decisions because we’d mapped the branches ahead of time.

One area where this thought made an outsized impact was compensation planning. Sales comp is notoriously fragile under volatility. We redesigned quota targets and commission accelerators using scenario bands, not fixed assumptions. We tested payout curves under best, base, and downside cases. We then ran Monte Carlo simulations to see how frequently actuals would fall into the “too much upside” or “demotivating downside” zones. This led to more durable comp plans, which meant fewer panicked mid-year resets. Our reps trusted the system. And our CFO team could model cost predictability with far greater confidence.

In retrospection, all these loops back to a single mindset shift: you don’t plan to be right. You plan to stay in the game. And staying in the game requires options that are well-designed, embedded into the process, and respected by every function. Sales needs to know they can escalate an expansion offer once particular customer signals fire. Success needs to know they have the budget authority to engage support when early churn flags arise. Product needs to know they can pause a roadmap stream if NPV no longer justifies it. And finance needs to know that its most significant power is not in control, but in preparation.

Today, when I walk into a revenue operations review or a strategic planning offsite, I do not bring a budget with fixed forecasts. I get a map. It has branches. It has signals. It has gates. And it has options, and each one designed not to predict the future, but to help us meet it with composure, and to move quickly when the fog clears.

Because in the world I have operated in, spanning economic cycles, geopolitical events, sudden buyer hesitation, system failures, and moments of exponential product success since 1994 until now, one principle has held. The companies that win are not the ones who guess right. They are the ones who remain ready. And readiness, I have learned, is the true hallmark of a great CFO.

Bias and Error: Human and Organizational Tradeoff

“I spent a lifetime trying to avoid my own mental biases. A.) I rub my own nose into my own mistakes. B.) I try and keep it simple and fundamental as much as I can. And, I like the engineering concept of a margin of safety. I’m a very blocking and tackling kind of thinker. I just try to avoid being stupid. I have a way of handling a lot of problems — I put them in what I call my ‘too hard pile,’ and just leave them there. I’m not trying to succeed in my ‘too hard pile.’” : Charlie Munger — 2020 CalTech Distinguished Alumni Award interview

Bias is a disproportionate weight in favor of or against an idea or thing, usually in a way that is closed-minded, prejudicial, or unfair. Biases can be innate or learned. People may develop biases for or against an individual, a group, or a belief. In science and engineering, a bias is a systematic error. Statistical bias results from an unfair sampling of a population, or from an estimation process that does not give accurate results on average.

Error refers to a outcome that is different from reality within the context of the objective function that is being pursued.

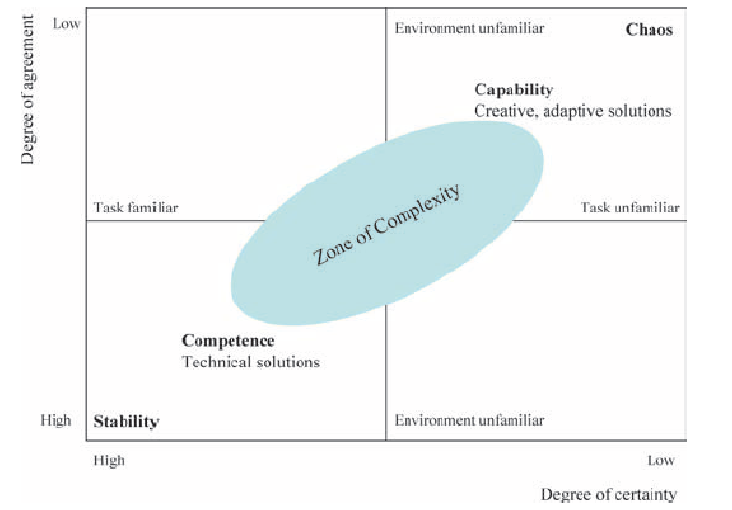

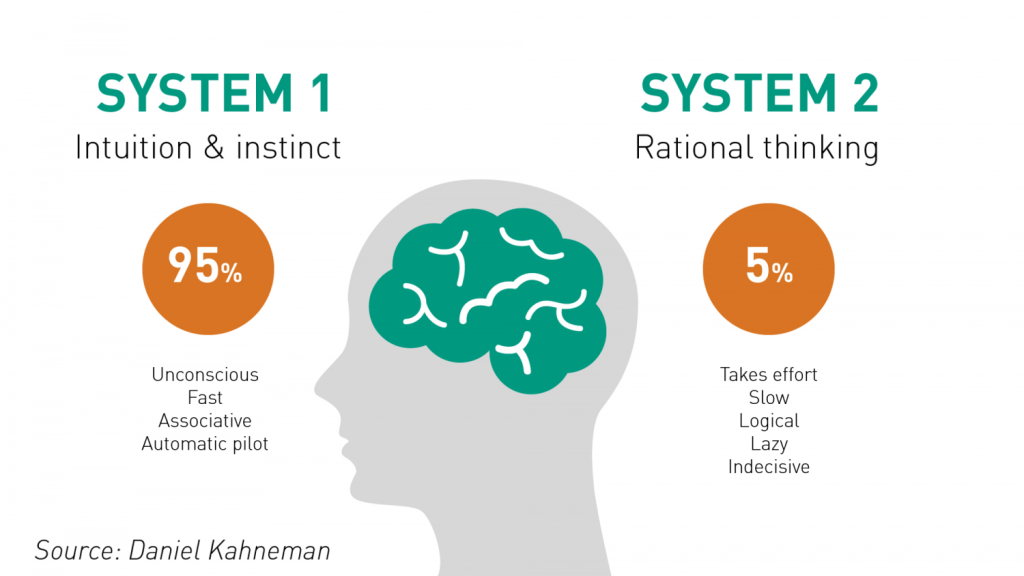

Thus, I would like to think that the Bias is a process that might lead to an Error. However, that is not always the case. There are instances where a bias might get you to an accurate or close to an accurate result. Is having a biased framework always a bad thing? That is not always the case. From an evolutionary standpoint, humans have progressed along the dimension of making rapid judgements – and much of them stemming from experience and their exposure to elements in society. Rapid judgements are typified under the System 1 judgement (Kahneman, Tversky) which allows bias and heuristic to commingle to effectively arrive at intuitive decision outcomes.

And again, the decision framework constitutes a continually active process in how humans or/and organizations execute upon their goals. It is largely an emotional response but could just as well be an automated response to a certain stimulus. However, there is a danger prevalent in System 1 thinking: it might lead one to comfortably head toward an outcome that is seemingly intuitive, but the actual result might be significantly different and that would lead to an error in the judgement. In math, you often hear the problem of induction which establishes that your understanding of a future outcome relies on the continuity of the past outcomes, and that is an errant way of thinking although it still represents a useful tool for us to advance toward solutions.

System 2 judgement emerges as another means to temper the more significant variabilities associated with System 1 thinking. System 2 thinking represents a more deliberate approach which leads to a more careful construct of rationale and thought. It is a system that slows down the decision making since it explores the logic, the assumptions, and how the framework tightly fits together to test contexts. There are a more lot more things at work wherein the person or the organization has to invest the time, focus the efforts and amplify the concentration around the problem that has to be wrestled with. This is also the process where you search for biases that might be at play and be able to minimize or remove that altogether. Thus, each of the two Systems judgement represents two different patterns of thinking: rapid, more variable and more error prone outcomes vs. slow, stable and less error prone outcomes.

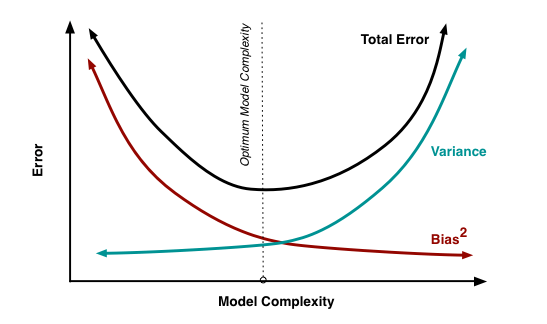

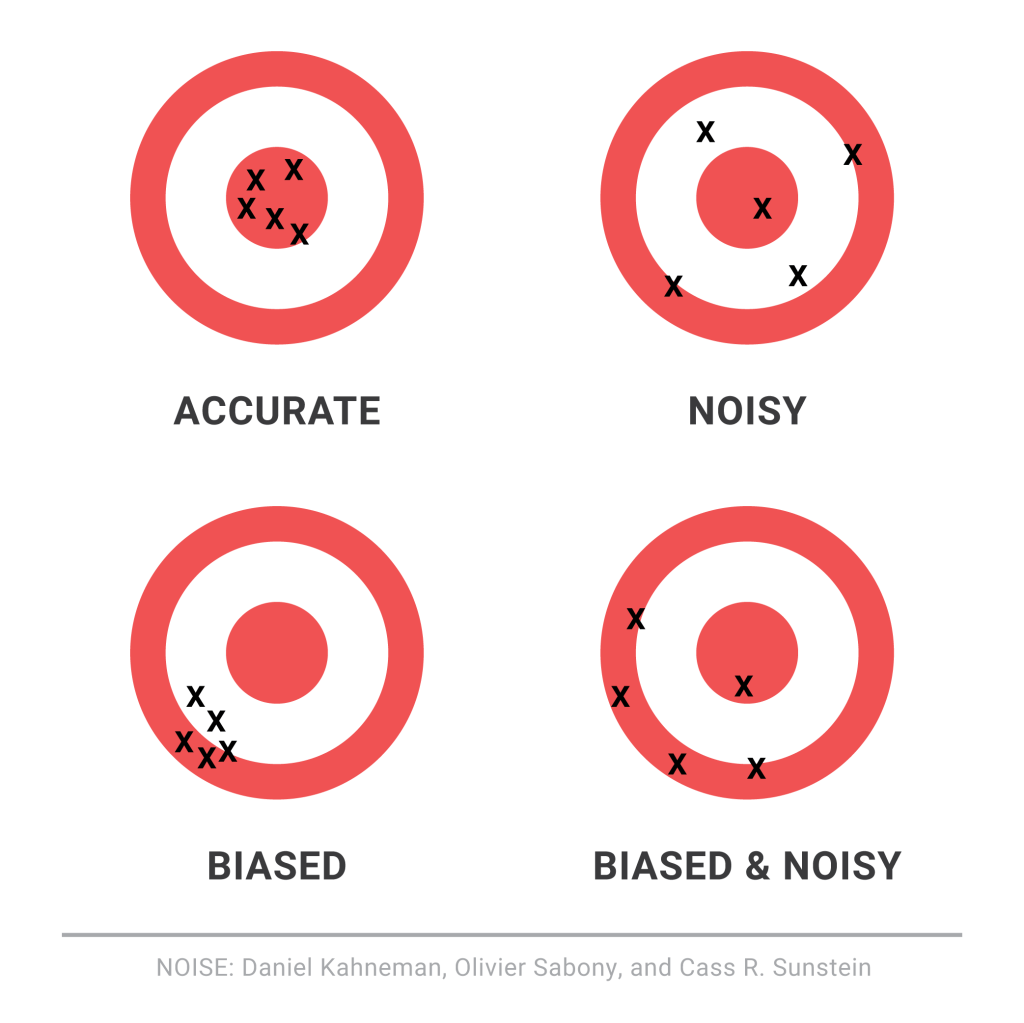

So let us revisit the Bias vs. Variance tradeoff. The idea is that the more bias you bring to address a problem, there is less variance in the aggregate. That does not mean that you are accurate. It only means that there is less variance in the set of outcomes, even if all of the outcomes are materially wrong. But it limits the variance since the bias enforces a constraint in the hypotheses space leading to a smaller and closely knit set of probabilistic outcomes. If you were to remove the constraints in the hypotheses space – namely, you remove bias in the decision framework – well, you are faced with a significant number of possibilities that would result in a larger spread of outcomes. With that said, the expected value of those outcomes might actually be closer to reality, despite the variance – than a framework decided upon by applying heuristic or operating in a bias mode.

So how do we decide then? Jeff Bezos had mentioned something that I recall: some decisions are one-way street and some are two-way. In other words, there are some decisions that cannot be undone, for good or for bad. It is a wise man who is able to anticipate that early on to decide what system one needs to pursue. An organization makes a few big and important decisions, and a lot of small decisions. Identify the big ones and spend oodles of time and encourage a diverse set of input to work through those decisions at a sufficiently high level of detail. When I personally craft rolling operating models, it serves a strategic purpose that might sit on shifting sands. That is perfectly okay! But it is critical to evaluate those big decisions since the crux of the effectiveness of the strategy and its concomitant quantitative representation rests upon those big decisions. Cutting corners can lead to disaster or an unforgiving result!

I will focus on the big whale decisions now. I will assume, for the sake of expediency, that the series of small decisions, in the aggregate or by itself, will not sufficiently be large enough that it would take us over the precipice. (It is also important however to examine the possibility that a series of small decisions can lead to a more holistic unintended emergent outcome that might have a whale effect: we come across that in complexity theory that I have already touched on in a set of previous articles).

Cognitive Biases are the biggest mea culpas that one needs to worry about. Some of the more common biases are confirmation bias, attribution bias, the halo effect, the rule of anchoring, the framing of the problem, and status quo bias. There are other cognition biases at play, but the ones listed above are common in planning and execution. It is imperative that these biases be forcibly peeled off while formulating a strategy toward problem solving.

But then there are also the statistical biases that one needs to be wary of. How we select data or selection bias plays a big role in validating information. In fact, if there are underlying statistical biases, the validity of the information is questionable. Then there are other strains of statistical biases: the forecast bias which is the natural tendency to be overtly optimistic or pessimistic without any substantive evidence to support one or the other case. Sometimes how the information is presented: visually or in tabular format – can lead to sins of the error of omission and commission leading the organization and judgement down paths that are unwarranted and just plain wrong. Thus, it is important to be aware of how statistical biases come into play to sabotage your decision framework.

One of the finest illustrations of misjudgment has been laid out by Charlie Munger. Here is the excerpt link : https://fs.blog/great-talks/psychology-human-misjudgment/ He lays out a very comprehensive 25 Biases that ail decision making. Once again, stripping biases do not necessarily result in accuracy — it increases the variability of outcomes that might be clustered around a mean that might be closer to accuracy than otherwise.

Variability is Noise. We do not know a priori what the expected mean is. We are close, but not quite. There is noise or a whole set of outcomes around the mean. Viewing things closer to the ground versus higher would still create a likelihood of accepting a false hypothesis or rejecting a true one. Noise is extremely hard to sift through, but how you can sift through the noise to arrive at those signals that are determining factors, is critical to organization success. To get to this territory, we have eliminated the cognitive and statistical biases. Now is the search for the signal. What do we do then? An increase in noise impairs accuracy. To improve accuracy, you either reduce noise or figure out those indicators that signal an accurate measure.

This is where algorithmic thinking comes into play. You start establishing well tested algorithms in specific use cases and cross-validate that across a large set of experiments or scenarios. It has been proved that algorithmic tools are, in the aggregate, superior to human judgement – since it systematically can surface causal and correlative relationships. Furthermore, special tools like principal component analysis and factory analysis can incorporate a large input variable set and establish the patterns that would be impregnable for even System 2 mindset to comprehend. This will bring decision making toward the signal variants and thus fortify decision making.

The final element is to assess the time commitment required to go through all the stages. Given infinite time and resources, there is always a high likelihood of arriving at those signals that are material for sound decision making. Alas, the reality of life does not play well to that assumption! Time and resources are constraints … so one must make do with sub-optimal decision making and establish a cutoff point wherein the benefits outweigh the risks of looking for another alternative. That comes down to the realm of judgements. While George Stigler, a Nobel Laureate in Economics, introduce search optimization in fixed sequential search – a more concrete example has been illustrated in “Algorithms to Live By” by Christian & Griffiths. They suggested an holy grail response: 37% is the accurate answer. In other words, you would reach a suboptimal decision by ensuring that you have explored up to 37% of your estimated maximum effort. While the estimated maximum effort is quite ambiguous and afflicted with all of the elements of bias (cognitive and statistical), the best thinking is to be as honest as possible to assess that effort and then draw your search threshold cutoff.

An important element of leadership is about making calls. Good calls, not necessarily the best calls! Calls weighing all possible circumstances that one can, being aware of the biases, bringing in a diverse set of knowledge and opinions, falling back upon agnostic tools in statistics, and knowing when it is appropriate to have learnt enough to pull the trigger. And it is important to cascade the principles of decision making and the underlying complexity into and across the organization.

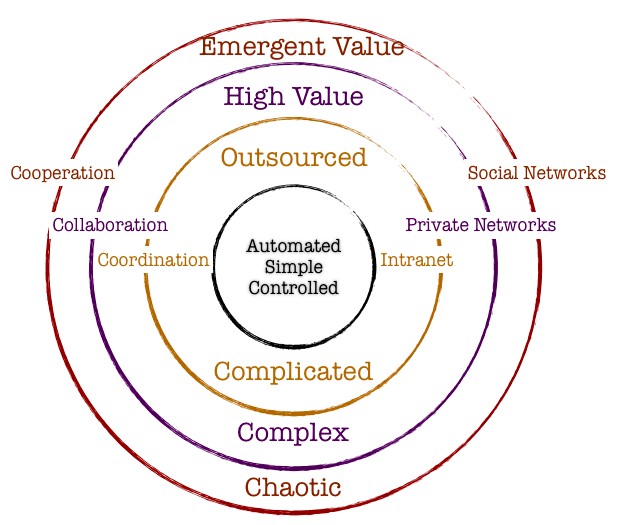

Navigating Chaos and Model Thinking

An inherent property of a chaotic system is that slight changes in initial conditions in the system result in a disproportionate change in outcome that is difficult to predict. Chaotic systems appear to create outcomes that appear to be random: they are generated by simple and non-random processes but the complexity of such systems emerge over time driven by numerous iterations of simple rules. The elements that compose chaotic systems might be few in number, but these elements work together to produce an intricate set of dynamics that amplifies the outcome and makes it hard to be predictable. These systems evolve over time, doing so according to rules and initial conditions and how the constituent elements work together.

Complex systems are characterized by emergence. The interactions between the elements of the system with its environment create new properties which influence the structural development of the system and the roles of the agents. In such systems there is self-organization characteristics that occur, and hence it is difficult to study and effect a system by studying the constituent parts that comprise it. The task becomes even more formidable when one faces the prevalent reality that most systems exhibit non-linear dynamics.

So how do we incorporate management practices in the face of chaos and complexity that is inherent in organization structure and market dynamics? It would be interesting to study this in light of the evolution of management principles in keeping with the evolution of scientific paradigms.

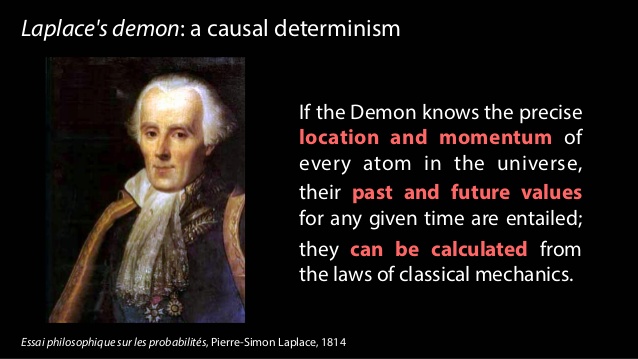

Newtonian Mechanics and Taylorism

Traditional organization management has been heavily influenced by Newtonian mechanics. The five key assumptions of Newtonian mechanics are:

- Reality is objective

- Systems are linear and there is a presumption that all underlying cause and effect are linear

- Knowledge is empirical and acquired through collecting and analyzing data with the focus on surfacing regularities, predictability and control

- Systems are inherently efficient. Systems almost always follows the path of least resistance

- If inputs and process is managed, the outcomes are predictable

Frederick Taylor is the father of operational research and his methods were deployed in automotive companies in the 1940’s. Workers and processes are input elements to ensure that the machine functions per expectations. There was a linearity employed in principle. Management role was that of observation and control and the system would best function under hierarchical operating principles. Mass and efficient production were the hallmarks of management goal.

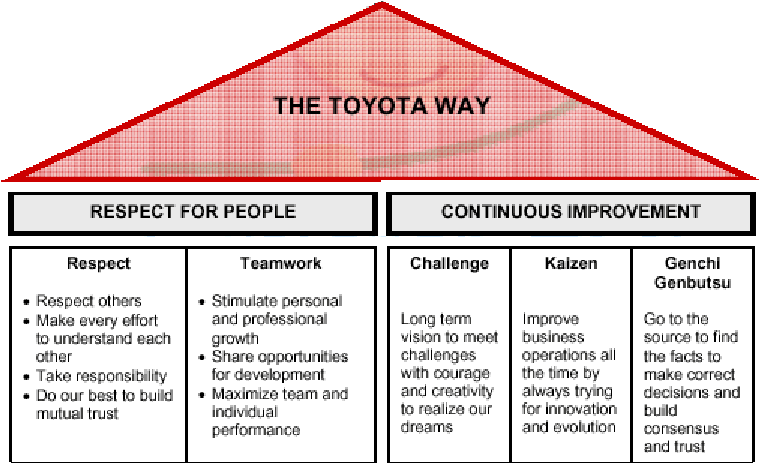

Randomness and the Toyota Way

The randomness paradigm recognized uncertainty as a pervasive constant. The various methods that Toyota Way invoked around 5W rested on the assumption that understanding the cause and effect is instrumental and this inclined management toward a more process-based deployment. Learning is introduced in this model as a dynamic variable and there is a lot of emphasis on the agents and providing them the clarity and purpose of their tasks. Efficiencies and quality are presumably driven by the rank and file and autonomous decisions are allowed. The management principle moves away from hierarchical and top-down to a more responsibility driven labor force.

Complexity and Chaos and the Nimble Organization

Increasing complexity has led to more demands on the organization. With the advent of social media and rapid information distribution and a general rise in consciousness around social impact, organizations have to balance out multiple objectives. Any small change in initial condition can lead to major outcomes: an advertising mistake can become a global PR nightmare; a word taken out of context could have huge ramifications that might immediately reflect on the stock price; an employee complaint could force management change. Increasing data and knowledge are not sufficient to ensure long-term success. In fact, there is no clear recipe to guarantee success in an age fraught with non-linearity, emergence and disequilibrium. To succeed in this environment entails the development of a learning organization that is not governed by fixed top-down rules: rather the rules are simple and the guidance is around the purpose of the system or the organization. It is best left to intellectual capital to self-organize rapidly in response to external information to adapt and make changes to ensure organization resilience and success.

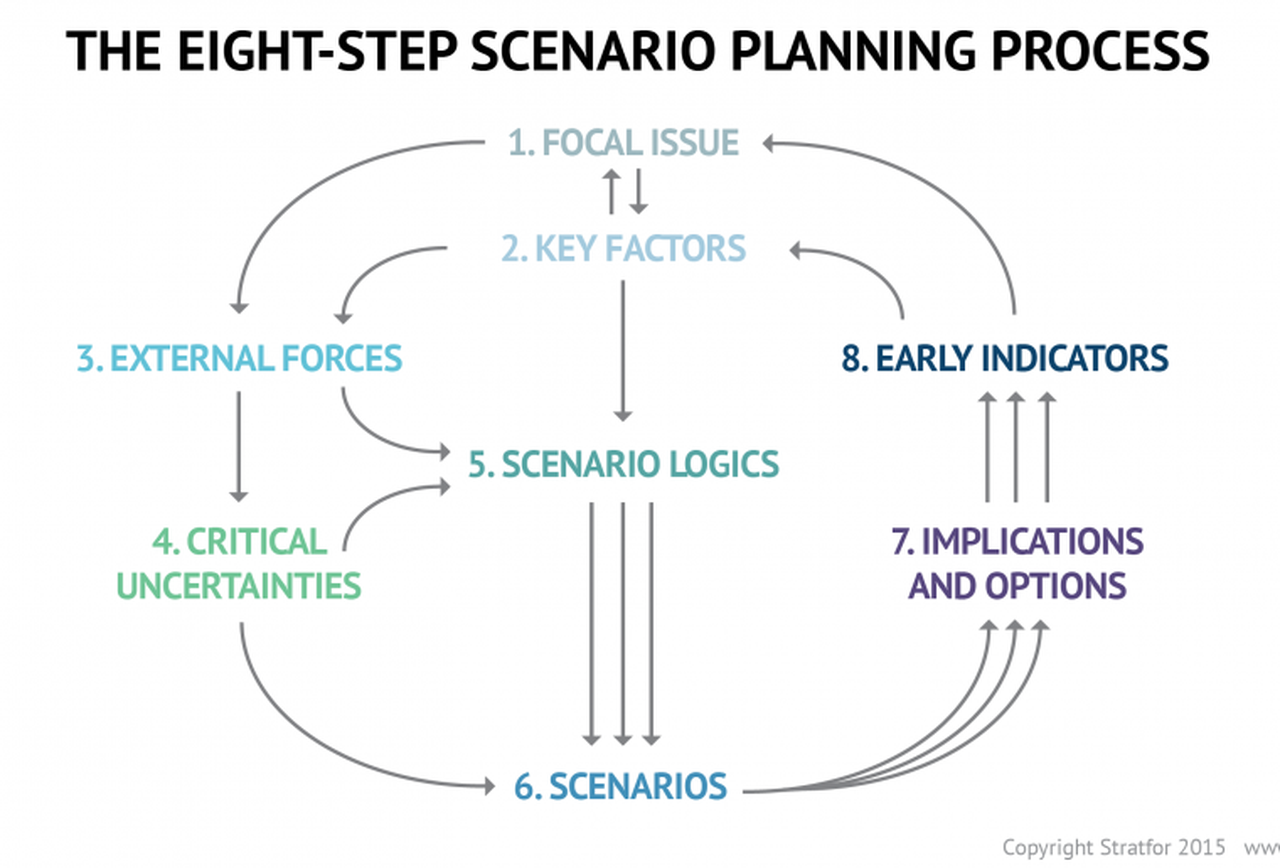

Companies are dynamic non-linear adaptive systems. The elements in the system are constantly interacting between themselves and their external environment. This creates new emergent properties that are sensitive to the initial conditions. A change in purpose or strategic positioning could set a domino effect and can lead to outcomes that are not predictable. Decisions are pushed out to all levels in the organization, since the presumption is that local and diverse knowledge that spontaneously emerge in response to stimuli is a superior structure than managing for complexity in a centralized manner. Thus, methods that can generate ideas, create innovation habitats, and embrace failures as providing new opportunities to learn are best practices that companies must follow. Traditional long-term planning and forecasting is becoming a far harder exercise and practically impossible. Thus, planning is more around strategic mindset, scenario planning, allowing local rules to auto generate without direct supervision, encourage dissent and diversity, stimulate creativity and establishing clarity of purpose and broad guidelines are the hall marks of success.

Principles of Leadership in a New Age

We have already explored the fact that traditional leadership models originated in the context of mass production and efficiencies. These models are arcane in our information era today, where systems are characterized by exponential dynamism of variables, increased density of interactions, increased globalization and interconnectedness, massive information distribution at increasing rapidity, and a general toward economies driven by free will of the participants rather than a central authority.

Complexity Leadership Theory (Uhl-Bien) is a “framework for leadership that enables the learning, creative and adaptive capacity of complex adaptive systems in knowledge-producing organizations or organizational units. Since planning for the long-term is virtually impossible, Leadership has to be armed with different tool sets to steer the organization toward achieving its purpose. Leaders take on enabler role rather than controller role: empowerment supplants control. Leadership is not about focus on traits of a single leader: rather, it redirects emphasis from individual leaders to leadership as an organizational phenomenon. Leadership is a trait rather than an individual. We recognize that complex systems have lot of interacting agents – in business parlance, which might constitute labor and capital. Introducing complexity leadership is to empower all of the agents with the ability to lead their sub-units toward a common shared purpose. Different agents can become leaders in different roles as their tasks or roles morph rapidly: it is not necessarily defined by a formal appointment or knighthood in title.

Thus, complexity of our modern-day reality demands a new strategic toolset for the new leader. The most important skills would be complex seeing, complex thinking, complex knowing, complex acting, complex trusting and complex being. (Elena Osmodo, 2012)

Complex Seeing: Reality is inherently subjective. It is a page of the Heisenberg Uncertainty principle that posits that the independence between the observer and the observed is not real. If leaders are not aware of this independence, they run the risk of engaging in decisions that are fraught with bias. They will continue to perceive reality with the same lens that they have perceived reality in the past, despite the fact that undercurrents and riptides of increasingly exponential systems are tearing away their “perceived reality.” Leader have to be conscious about the tectonic shifts, reevaluate their own intentions, probe and exclude biases that could cloud the fidelity of their decisions, and engage in a continuous learning process. The ability to sift and see through this complexity sets the initial condition upon which the entire system’s efficacy and trajectory rests.

Complex Thinking: Leaders have to be cognizant of falling prey to linear simple cause and effect thinking. On the contrary, leaders have to engage in counter-intuitive thinking, brainstorming and creative thinking. In addition, encouraging dissent, debates and diversity encourage new strains of thought and ideas.

Complex Feeling: Leaders must maintain high levels of energy and be optimistic of the future. Failures are not scoffed at; rather they are simply another window for learning. Leaders have to promote positive and productive emotional interactions. The leaders are tasked to increase positive feedback loops while reducing negative feedback mechanisms to the extent possible. Entropy and attrition taxes any system as is: the leader’s job is to set up safe environment to inculcate respect through general guidelines and leading by example.

Complex Knowing: Leadership is tasked with formulating simple rules to enable learned and quicker decision making across the organization. Leaders must provide a common purpose, interconnect people with symbols and metaphors, and continually reiterate the raison d’etre of the organization. Knowing is articulating: leadership has to articulate and be humble to any new and novel challenges and counterfactuals that might arise. The leader has to establish systems of knowledge: collective learning, collaborative learning and organizational learning. Collective learning is the ability of the collective to learn from experiences drawn from the vast set of individual actors operating in the system. Collaborative learning results due to interaction of agents and clusters in the organization. Learning organization, as Senge defines it, is “where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspirations are set free, and where people are continually learning to see the whole together.”

Complex Acting: Complex action is the ability of the leader to not only work toward benefiting the agents in his/her purview, but also to ensure that the benefits resonates to a whole which by definition is greater than the sum of the parts. Complex acting is to take specific action-oriented steps that largely reflect the values that the organization represents in its environmental context.

Complex Trusting: Decentralization requires conferring power to local agents. For decentralization to work effectively, leaders have to trust that the agents will, in the aggregate, work toward advancing the organization. The cost of managing top-down is far more than the benefits that a trust-based decentralized system would work in a dynamic environment resplendent with the novelty of chaos and complexity.

Complex Being: This is the ability of the leaser to favor and encourage communication across the organization rapidly. The leader needs to encourage relationships and inter-functional dialogue.

The role of complex leaders is to design adaptive systems that are able to cope with challenging and novel environments by establishing a few rules and encouraging agents to self-organize autonomously at local levels to solve challenges. The leader’s main role in this exercise is to set the strategic directions and the guidelines and let the organizations run.

Chaos and the tide of Entropy!

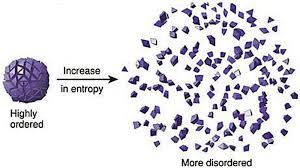

We have discussed chaos. It is rooted in the fundamental idea that small changes in the initial condition in a system can amplify the impact on the final outcome in the system. Let us now look at another sibling in systems literature – namely, the concept of entropy. We will then attempt to bridge these two concepts since they are inherent in all systems.

Entropy arises from the law of thermodynamics. Let us state all three laws:

- First law is known as the Lay of Conservation of Energy which states that energy can neither be created nor destroyed: energy can only be transferred from one form to another. Thus, if there is work in terms of energy transformation in a system, there is equivalent loss of energy transformation around the system. This fact balances the first law of thermodynamics.

- Second law of thermodynamics states that the entropy of any isolated system always increases. Entropy always increases, and rarely ever decreases. If a locker room is not tidied, entropy dictates that it will become messier and more disorderly over time. In other words, all systems that are stagnant will inviolably run against entropy which would lead to its undoing over time. Over time the state of disorganization increases. While energy cannot be created or destroyed, as per the First Law, it certainly can change from useful energy to less useful energy.

- Third law establishes that the entropy of a system approaches a constant value as the temperature approaches absolute zero. Thus, the entropy of a pure crystalline substance at absolute zero temperature is zero. However, if there is any imperfection that resides in the crystalline structure, there will be some entropy that will act upon it.

Entropy refers to a measure of disorganization. Thus people in a crowd that is widely spread out across a large stadium has high entropy whereas it would constitute low entropy if people are all huddled in one corner of the stadium. Entropy is the quantitative measure of the process – namely, how much energy has been spent from being localized to being diffused in a system. Entropy is enabled by motion or interaction of elements in a system, but is actualized by the process of interaction. All particles work toward spontaneously dissipating their energy if they are not curtailed from doing so. In other words, there is an inherent will, philosophically speaking, of a system to dissipate energy and that process of dissipation is entropy. However, it makes no effort to figure out how quickly entropy kicks into gear – it is this fact that makes it difficult to predict the overall state of the system.

Chaos, as we have already discussed, makes systems unpredictable because of perturbations in the initial state. Entropy is the dissipation of energy in the system, but there is no standard way of knowing the parameter of how quickly entropy would set in. There are thus two very interesting elements in systems that almost work simultaneously to ensure that predictability of systems become harder.

Another way of looking at entropy is to view this as a tax that the system charges us when it goes to work on our behalf. If we are purposefully calibrating a system to meet a certain purpose, there is inevitably a corresponding usage of energy or dissipation of energy otherwise known as entropy that is working in parallel. A common example that we are familiar with is mass industrialization initiatives. Mass industrialization has impacts on environment, disease, resource depletion, and a general decay of life in some form. If entropy as we understand it is an irreversible phenomenon, then there is virtually nothing that can be done to eliminate it. It is a permanent tax of varying magnitude in the system.

Humans have since early times have tried to formulate a working framework of the world around them. To do that, they have crafted various models and drawn upon different analogies to lend credence to one way of thinking over another. Either way, they have been left best to wrestle with approximations: approximations associated with their understanding of the initial conditions, approximations on model mechanics, approximations on the tax that the system inevitably charges, and the approximate distribution of potential outcomes. Despite valiant efforts to reduce the framework to physical versus behavioral phenomena, their final task of creating or developing a predictable system has not worked. While physical laws of nature describe physical phenomena, the behavioral laws describe non-deterministic phenomena. If linear equations are used as tools to understand the physical laws following the principles of classical Newtonian mechanics, the non-linear observations marred any consistent and comprehensive framework for clear understanding. Entropy reaches out toward an irreversible thermal death: there is an inherent fatalism associated with the Second Law of Thermodynamics. However, if that is presumed to be the case, how is it that human evolution has jumped across multiple chasms and have evolved to what it is today? If indeed entropy is the tax, one could argue that chaos with its bounded but amplified mechanics have allowed the human race to continue.

Let us now deliberate on this observation of Richard Feynmann, a Nobel Laurate in physics – “So we now have to talk about what we mean by disorder and what we mean by order. … Suppose we divide the space into little volume elements. If we have black and white molecules, how many ways could we distribute them among the volume elements so that white is on one side and black is on the other? On the other hand, how many ways could we distribute them with no restriction on which goes where? Clearly, there are many more ways to arrange them in the latter case.

We measure “disorder” by the number of ways that the insides can be arranged, so that from the outside it looks the same. The logarithm of that number of ways is the entropy. The number of ways in the separated case is less, so the entropy is less, or the “disorder” is less.” It is commonly also alluded to as the distinction between microstates and macrostates. Essentially, it says that there could be innumerable microstates although from an outsider looking in – there is only one microstate. The number of microstates hints at the system having more entropy.

In a different way, we ran across this wonderful example: A professor distributes chocolates to students in the class. He has 35 students but he distributes 25 chocolates. He throws those chocolates to the students and some students might have more than others. The students do not know that the professor had only 25 chocolates: they have presumed that there were 35 chocolates. So the end result is that the students are disconcerted because they perceive that the other students have more chocolates than they have distributed but the system as a whole shows that there are only 25 chocolates. Regardless of all of the ways that the 25 chocolates are configured among the students, the microstate is stable.

So what is Feynmann and the chocolate example suggesting for our purpose of understanding the impact of entropy on systems: Our understanding is that the reconfiguration or the potential permutations of elements in the system that reflect the various microstates hint at higher entropy but in reality has no impact on the microstate per se except that the microstate has inherently higher entropy. Does this mean that the macrostate thus has a shorter life-span? Does this mean that the microstate is inherently more unstable? Could this mean an exponential decay factor in that state? The answer to all of the above questions is not always. Entropy is a physical phenomenon but to abstract this out to enable a study of organic systems that represent super complex macrostates and arrive at some predictable pattern of decay is a bridge too far! If we were to strictly follow the precepts of the Second Law and just for a moment forget about Chaos, one could surmise that evolution is not a measure of progress, it is simply a reconfiguration.

Theodosius Dobzhansky, a well known physicist, says: “Seen in retrospect, evolution as a whole doubtless had a general direction, from simple to complex, from dependence on to relative independence of the environment, to greater and greater autonomy of individuals, greater and greater development of sense organs and nervous systems conveying and processing information about the state of the organism’s surroundings, and finally greater and greater consciousness. You can call this direction progress or by some other name.”

Harold Mosowitz says “Life is organization. From prokaryotic cells, eukaryotic cells, tissues and organs, to plants and animals, families, communities, ecosystems, and living planets, life is organization, at every scale. The evolution of life is the increase of biological organization, if it is anything. Clearly, if life originates and makes evolutionary progress without organizing input somehow supplied, then something has organized itself. Logical entropy in a closed system has decreased. This is the violation that people are getting at, when they say that life violates the second law of thermodynamics. This violation, the decrease of logical entropy in a closed system, must happen continually in the Darwinian account of evolutionary progress.”

Entropy occurs in all systems. That is an indisputable fact. However, if we start defining boundaries, then we are prone to see that these bounded systems decay faster. However, if we open up the system to leave it unbounded, then there are a lot of other forces that come into play that is tantamount to some net progress. While it might be true that energy balances out, what we miss as social scientists or model builders or avid students of systems – we miss out on indices that reflect on leaps in quality and resilience and a horde of other factors that stabilizes the system despite the constant and ominous presence of entropy’s inner workings.

Managing Scale

| I think the most difficult thing had been scaling the infrastructure. Trying to support the response we had received from our users and the number of people that were interested in using the software. – Shawn Fanning |

Froude’s number? It is defined as the square of the ship’s velocity divided by its length and multiplied by the acceleration caused by gravity. So why are we introducing ships in this chapter? As I have done before, I am liberally standing on the shoulder of the giant, Geoffrey West, and borrowing from his account on the importance of the Froude’s number and the practical implications. Since ships are subject to turbulence, using a small model that works in a simulated turbulent environment might not work when we manufacture a large ship that is facing the ebbs and troughs of a finicky ocean. The workings and impact of turbulence is very complex, and at scale it becomes even more complex. Froude’s key contribution was to figure out a mathematical pathway of how to efficiently and effectively scale from a small model to a practical object. He did that by using a ratio as the common denominator. Mr. West provides an example that hits home: How fast does a 10-foot-long ship have to move to mimic the motion of a 700-foot-long ship moving at 20 knots. If they are to have the same Froude number (that is, the same value of the square of their velocity divided by their length), then the velocity has to scale as the square root of their lengths. The ratio of the square root of their lengths is the the square of 700 feet of the ship/10 feet of the model ship which turns out to be the square of 70. For the 10-foot model to mimic the motion of a large ship, it must move at the speed of 20 knots/ square of 70 or 2.5 knots. The Froude number is still widely used across many fields today to bridge small scale and large-scale thinking. Although this number applies to physical systems, the notion that adaptive systems can be similarly bridged through appropriate mathematical equations. Unfortunately, because of the increased number of variables impacting adaptive systems and all of these variables working and learning from one another, the task of establishing a Froude number becomes diminishingly small.

The other concept that has gained wide attention is the science of allometry. Allometry essentially states that as size increases, then the form of the object would change. Allometric scaling governs all complex physical and adaptive systems. So the question is whether there are some universal laws or mathematics that can be used to enable us to better understand or predict scale impacts. Let us extend this thinking a bit further. If sizes influence form and form constitute all sub-physical elements, then it would stand to reason that a universal law or a set of equations can provide deep explanatory powers on scale and systems. One needs to bear in mind that even what one might consider a universal law might be true within finite observations and boundaries. In other words, if there are observations that fall outside of those boundaries, one is forced into resetting our belief in the universal law or to frame a new paradigm to cover these exigencies. I mention this because as we seek to understand business and global grand challenges considering the existence of complexity, scale, chaos and seeming disorder – we might also want to embrace multiple laws or formulations working at different hierarchies and different data sets to arrive at satisficing solutions to the problems that we want to wrestle with.

Physics and mathematics allow a qualitatively high degree of predictability. One can craft models across different scales to make a sensible approach on how to design for scale. If you were to design a prototype using a 3D printer and decide to scale that prototype a 100X, there are mathematical scalar components that are factored into the mechanics to allow for some sort of equivalence which would ultimately lead to the final product fulfilling its functional purpose in a complex physical system. But how does one manage scale in light of those complex adaptive systems that emerge due to human interactions, evolution of organization, uncertainty of the future, and dynamic rules that could rapidly impact the direction of a company?

Is scale a single measure? Or is it a continuum? In our activities, we intentionally or unintentionally invoke scale concepts. What is the most efficient scale to measure an outcome, so we can make good policy decisions, how do we apply our learning from one scale to a system that operates on another scale and how do we assess how sets of phenomena operate at different scales, spatially and temporally, and how they impact one another? Now the most interesting question: Is scale polymorphous? Does the word scale have different meanings in different contexts? When we talk about microbiology, we are operating at micro-scales. When we talk at a very macro level, our scales are huge. In business, we regard scale with respect to how efficiently we grow. In one way, it is a measure but for the following discussion, we will interpret scale as non-linear growth expending fewer and fewer resources to support that growth as a ratio.

As we had discussed previously, complex adaptive systems self-organize over time. They arrive at some steady state outcome without active intervention. In fact, the active intervention might lead to unintended consequences that might even spell doom for the system that is being influenced. So as an organization scales, it is important to keep this notion of rapid self-organization in mind which will inform us to make or not make certain decisions from a central or top-down perspective. In other words, part of managing scale successfully is to not manage it at a coarse-grained level.

The second element of successfully managing scale is to understand the constraints that prevent scale. There is an entire chapter dedicated to the theory of constraints which sheds light on why this is a fundamental process management technique that increases the pace of the system. But for our purposes in this section, we will summarize as follows: every system as it grows have constraints. It is important to understand the constraints because these constraints slow the system: the bottlenecks have to be removed. And once one constraint is removed, then one comes across another constraint. The system is a chain of events and it is imperative that all of these events are identified. The weakest links harangue the systems and these weakest links have to be either cleared or resourced to enable the system to scale. It is a continuous process of observation and tweaking the results with the established knowledge that the demons of uncertainty and variability can reset the entire process and one might have to start again. Despite that fact, constraint management is an effective method to negotiate and manage scale.

The third element is devising the appropriate organization architecture. As one projects into the future, management might be inclined toward developing and investing in the architecture early to accommodate the scale. Overinvestment in the architecture might not be efficient. As mentioned, cities and social systems that grow 100% require 85% investment in infrastructure: in other words, systems grow on a sublinear scale from an infrastructure perspective. How does management of scale arrive at the 85%? It is nigh impossible, but it is important to reserve that concept since it informs management to architect the infrastructure cautiously. Large investments upfront could be a waste or could slow the system down: alternative, investments that are postponed a little too late can also impact the system adversely.

The fourth element of managing scale is to focus your lens of opportunity. In macroecology, we can arrive at certain conclusions when we regard the system from a distance versus very closely. We can subsume our understanding into one big bucket called climate change and then we figure out different ways to manage the complexity that causes the climate change by invoking certain policies and incentives at a macro level. However, if we go closer, we might decide to target a very specific contributor to climate change – namely, fossil fuels. The theory follows that to manage the dynamic complexity and scale of climate impact – it would be best to address a major factor which, in this case, would be fossil fuels. The equivalence of this in a natural business setting would be to establish and focus the strategy for scale in a niche vertical or a relatively narrower set of opportunities. Even though we are working in the web of complex adaptive systems, we might devise strategies to directionally manage the business within the framework of complex physical systems where we have an understanding of the slight variations of initial state and the realization that the final outcome might be broad but yet bounded for intentional management.

The final element is the management of initial states. Complex physical systems are governed by variation in initial states. Perturbation of these initial states can lead to a wide divergence of outcomes, albeit bounded within a certain frame of reference. It is difficult perhaps to gauge all the interactions that might occur from a starting point to the outcome, although we agree that a few adjustments like decentralization of decision making, constraint management, optimal organization structure and narrowing the playing field would be helpful.