Blog Archives

Bias and Error: Human and Organizational Tradeoff

“I spent a lifetime trying to avoid my own mental biases. A.) I rub my own nose into my own mistakes. B.) I try and keep it simple and fundamental as much as I can. And, I like the engineering concept of a margin of safety. I’m a very blocking and tackling kind of thinker. I just try to avoid being stupid. I have a way of handling a lot of problems — I put them in what I call my ‘too hard pile,’ and just leave them there. I’m not trying to succeed in my ‘too hard pile.’” : Charlie Munger — 2020 CalTech Distinguished Alumni Award interview

Bias is a disproportionate weight in favor of or against an idea or thing, usually in a way that is closed-minded, prejudicial, or unfair. Biases can be innate or learned. People may develop biases for or against an individual, a group, or a belief. In science and engineering, a bias is a systematic error. Statistical bias results from an unfair sampling of a population, or from an estimation process that does not give accurate results on average.

Error refers to a outcome that is different from reality within the context of the objective function that is being pursued.

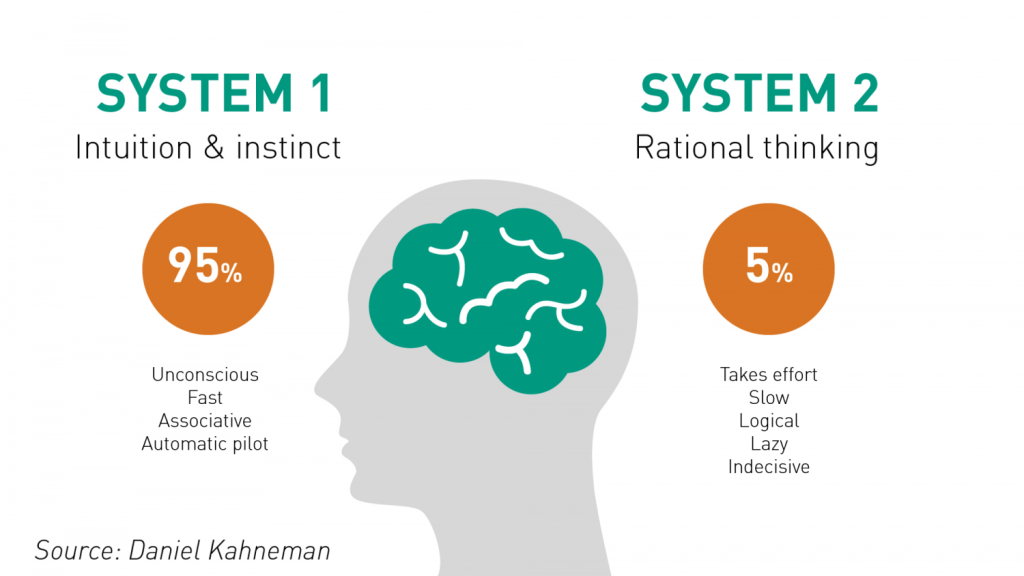

Thus, I would like to think that the Bias is a process that might lead to an Error. However, that is not always the case. There are instances where a bias might get you to an accurate or close to an accurate result. Is having a biased framework always a bad thing? That is not always the case. From an evolutionary standpoint, humans have progressed along the dimension of making rapid judgements – and much of them stemming from experience and their exposure to elements in society. Rapid judgements are typified under the System 1 judgement (Kahneman, Tversky) which allows bias and heuristic to commingle to effectively arrive at intuitive decision outcomes.

And again, the decision framework constitutes a continually active process in how humans or/and organizations execute upon their goals. It is largely an emotional response but could just as well be an automated response to a certain stimulus. However, there is a danger prevalent in System 1 thinking: it might lead one to comfortably head toward an outcome that is seemingly intuitive, but the actual result might be significantly different and that would lead to an error in the judgement. In math, you often hear the problem of induction which establishes that your understanding of a future outcome relies on the continuity of the past outcomes, and that is an errant way of thinking although it still represents a useful tool for us to advance toward solutions.

System 2 judgement emerges as another means to temper the more significant variabilities associated with System 1 thinking. System 2 thinking represents a more deliberate approach which leads to a more careful construct of rationale and thought. It is a system that slows down the decision making since it explores the logic, the assumptions, and how the framework tightly fits together to test contexts. There are a more lot more things at work wherein the person or the organization has to invest the time, focus the efforts and amplify the concentration around the problem that has to be wrestled with. This is also the process where you search for biases that might be at play and be able to minimize or remove that altogether. Thus, each of the two Systems judgement represents two different patterns of thinking: rapid, more variable and more error prone outcomes vs. slow, stable and less error prone outcomes.

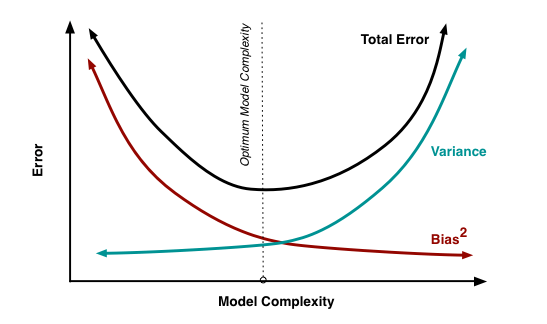

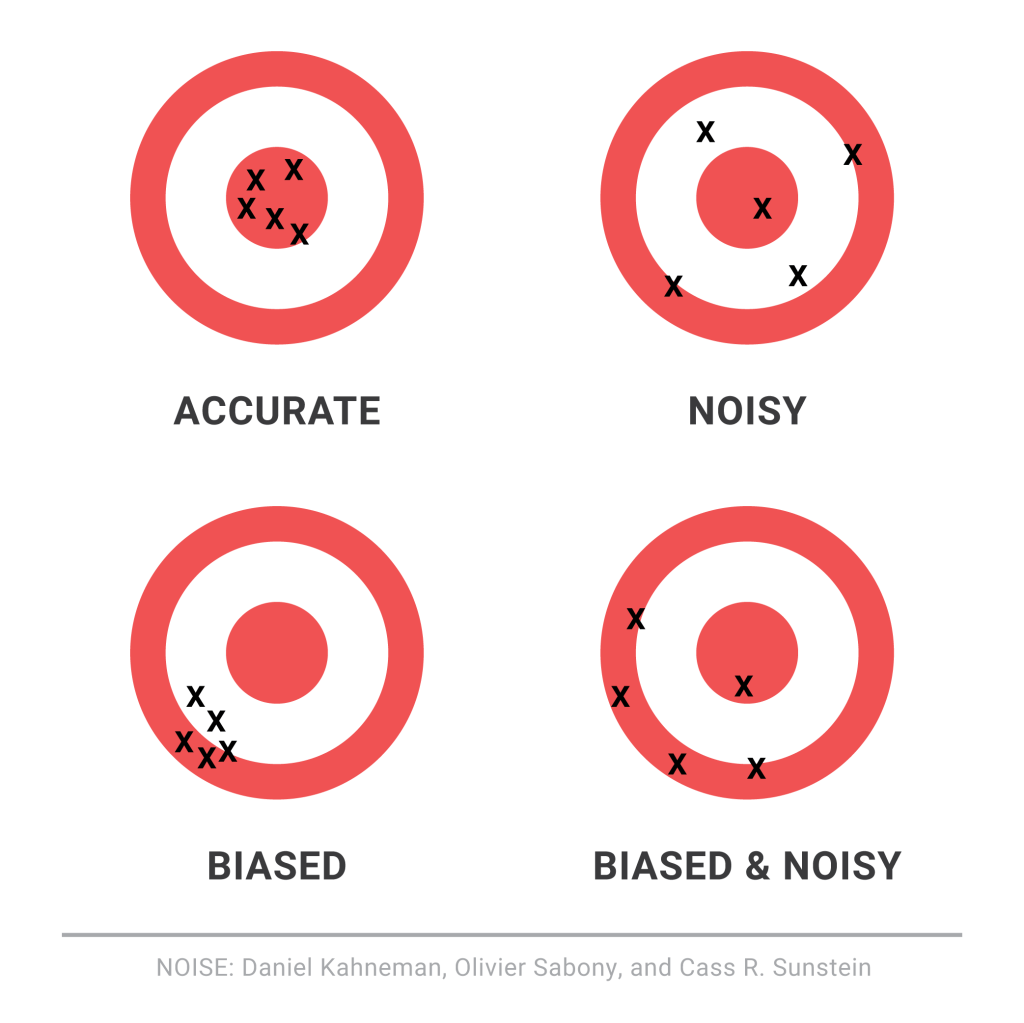

So let us revisit the Bias vs. Variance tradeoff. The idea is that the more bias you bring to address a problem, there is less variance in the aggregate. That does not mean that you are accurate. It only means that there is less variance in the set of outcomes, even if all of the outcomes are materially wrong. But it limits the variance since the bias enforces a constraint in the hypotheses space leading to a smaller and closely knit set of probabilistic outcomes. If you were to remove the constraints in the hypotheses space – namely, you remove bias in the decision framework – well, you are faced with a significant number of possibilities that would result in a larger spread of outcomes. With that said, the expected value of those outcomes might actually be closer to reality, despite the variance – than a framework decided upon by applying heuristic or operating in a bias mode.

So how do we decide then? Jeff Bezos had mentioned something that I recall: some decisions are one-way street and some are two-way. In other words, there are some decisions that cannot be undone, for good or for bad. It is a wise man who is able to anticipate that early on to decide what system one needs to pursue. An organization makes a few big and important decisions, and a lot of small decisions. Identify the big ones and spend oodles of time and encourage a diverse set of input to work through those decisions at a sufficiently high level of detail. When I personally craft rolling operating models, it serves a strategic purpose that might sit on shifting sands. That is perfectly okay! But it is critical to evaluate those big decisions since the crux of the effectiveness of the strategy and its concomitant quantitative representation rests upon those big decisions. Cutting corners can lead to disaster or an unforgiving result!

I will focus on the big whale decisions now. I will assume, for the sake of expediency, that the series of small decisions, in the aggregate or by itself, will not sufficiently be large enough that it would take us over the precipice. (It is also important however to examine the possibility that a series of small decisions can lead to a more holistic unintended emergent outcome that might have a whale effect: we come across that in complexity theory that I have already touched on in a set of previous articles).

Cognitive Biases are the biggest mea culpas that one needs to worry about. Some of the more common biases are confirmation bias, attribution bias, the halo effect, the rule of anchoring, the framing of the problem, and status quo bias. There are other cognition biases at play, but the ones listed above are common in planning and execution. It is imperative that these biases be forcibly peeled off while formulating a strategy toward problem solving.

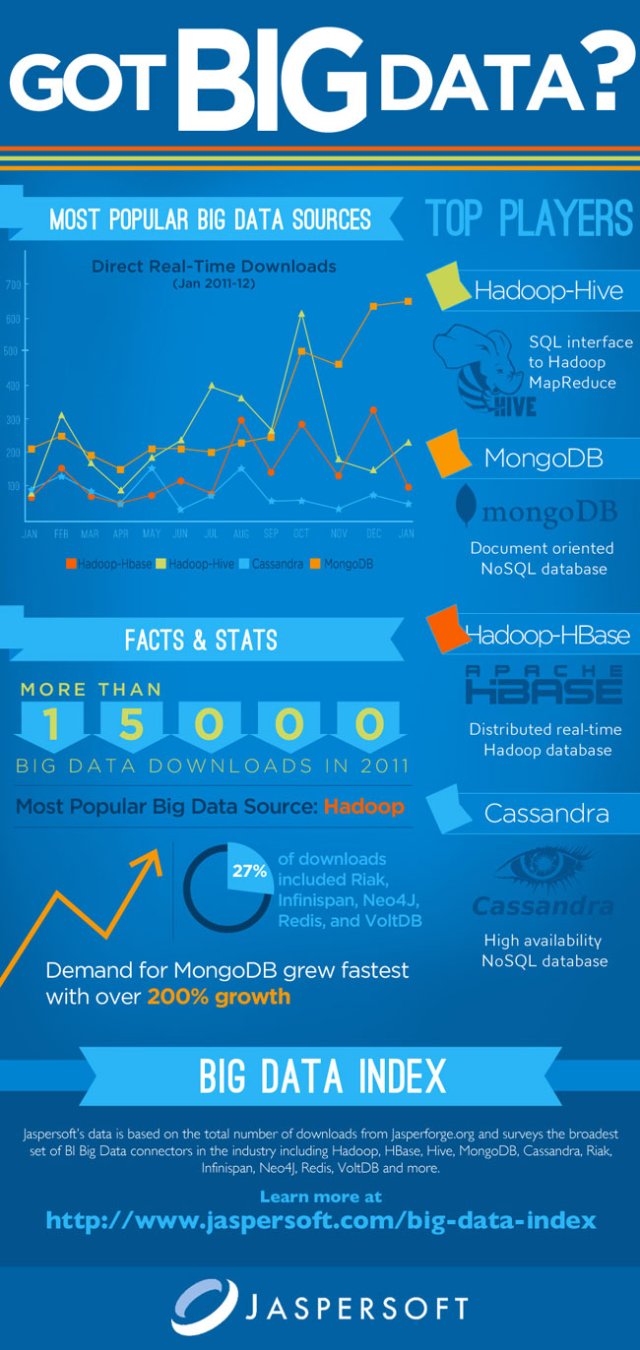

But then there are also the statistical biases that one needs to be wary of. How we select data or selection bias plays a big role in validating information. In fact, if there are underlying statistical biases, the validity of the information is questionable. Then there are other strains of statistical biases: the forecast bias which is the natural tendency to be overtly optimistic or pessimistic without any substantive evidence to support one or the other case. Sometimes how the information is presented: visually or in tabular format – can lead to sins of the error of omission and commission leading the organization and judgement down paths that are unwarranted and just plain wrong. Thus, it is important to be aware of how statistical biases come into play to sabotage your decision framework.

One of the finest illustrations of misjudgment has been laid out by Charlie Munger. Here is the excerpt link : https://fs.blog/great-talks/psychology-human-misjudgment/ He lays out a very comprehensive 25 Biases that ail decision making. Once again, stripping biases do not necessarily result in accuracy — it increases the variability of outcomes that might be clustered around a mean that might be closer to accuracy than otherwise.

Variability is Noise. We do not know a priori what the expected mean is. We are close, but not quite. There is noise or a whole set of outcomes around the mean. Viewing things closer to the ground versus higher would still create a likelihood of accepting a false hypothesis or rejecting a true one. Noise is extremely hard to sift through, but how you can sift through the noise to arrive at those signals that are determining factors, is critical to organization success. To get to this territory, we have eliminated the cognitive and statistical biases. Now is the search for the signal. What do we do then? An increase in noise impairs accuracy. To improve accuracy, you either reduce noise or figure out those indicators that signal an accurate measure.

This is where algorithmic thinking comes into play. You start establishing well tested algorithms in specific use cases and cross-validate that across a large set of experiments or scenarios. It has been proved that algorithmic tools are, in the aggregate, superior to human judgement – since it systematically can surface causal and correlative relationships. Furthermore, special tools like principal component analysis and factory analysis can incorporate a large input variable set and establish the patterns that would be impregnable for even System 2 mindset to comprehend. This will bring decision making toward the signal variants and thus fortify decision making.

The final element is to assess the time commitment required to go through all the stages. Given infinite time and resources, there is always a high likelihood of arriving at those signals that are material for sound decision making. Alas, the reality of life does not play well to that assumption! Time and resources are constraints … so one must make do with sub-optimal decision making and establish a cutoff point wherein the benefits outweigh the risks of looking for another alternative. That comes down to the realm of judgements. While George Stigler, a Nobel Laureate in Economics, introduce search optimization in fixed sequential search – a more concrete example has been illustrated in “Algorithms to Live By” by Christian & Griffiths. They suggested an holy grail response: 37% is the accurate answer. In other words, you would reach a suboptimal decision by ensuring that you have explored up to 37% of your estimated maximum effort. While the estimated maximum effort is quite ambiguous and afflicted with all of the elements of bias (cognitive and statistical), the best thinking is to be as honest as possible to assess that effort and then draw your search threshold cutoff.

An important element of leadership is about making calls. Good calls, not necessarily the best calls! Calls weighing all possible circumstances that one can, being aware of the biases, bringing in a diverse set of knowledge and opinions, falling back upon agnostic tools in statistics, and knowing when it is appropriate to have learnt enough to pull the trigger. And it is important to cascade the principles of decision making and the underlying complexity into and across the organization.

Building a Lean Financial Infrastructure!

A lean financial infrastructure presumes the ability of every element in the value chain to preserve and generate cash flow. That is the fundamental essence of the lean infrastructure that I espouse. So what are the key elements that constitute a lean financial infrastructure?

And given the elements, what are the key tweaks that one must continually make to ensure that the infrastructure does not fall into entropy and the gains that are made fall flat or decay over time. Identification of the blocks and monitoring and making rapid changes go hand in hand.

The Key Elements or the building blocks of a lean finance organization are as follows:

- Chart of Accounts: This is the critical unit that defines the starting point of the organization. It relays and groups all of the key economic activities of the organization into a larger body of elements like revenue, expenses, assets, liabilities and equity. Granularity of these activities might lead to a fairly extensive chart of account and require more work to manage and monitor these accounts, thus requiring incrementally a larger investment in terms of time and effort. However, the benefits of granularity far exceeds the costs because it forces management to look at every element of the business.

- The Operational Budget: Every year, organizations formulate the operational budget. That is generally a bottoms up rollup at a granular level that would map to the Chart of Accounts. It might follow a top-down directive around what the organization wants to land with respect to income, expense, balance sheet ratios, et al. Hence, there is almost always a process of iteration in this step to finally arrive and lock down the Budget. Be mindful though that there are feeders into the budget that might relate to customers, sales, operational metrics targets, etc. which are part of building a robust operational budget.

- The Deep Dive into Variances: As you progress through the year and part of the monthly closing process, one would inquire about how the actual performance is tracking against the budget. Since the budget has been done at a granular level and mapped exactly to the Chart of Accounts, it thus becomes easier to understand and delve into the variances. Be mindful that every element of the Chart of Account must be evaluated. The general inclination is to focus on the large items or large variances, while skipping the small expenses and smaller variances. That method, while efficient, might not be effective in the long run to build a lean finance organization. The rule, in my opinion, is that every account has to be looked and the question should be – Why? If the management has agreed on a number in the budget, then why are the actuals trending differently. Could it have been the budget and that we missed something critical in that process? Or has there been a change in the underlying economics of the business or a change in activities that might be leading to these “unexpected variances”. One has to take a scalpel to both – favorable and unfavorable variances since one can learn a lot about the underlying drivers. It might lead to managerially doing more of the better and less of the worse. Furthermore, this is also a great way to monitor leaks in the organization. Leaks are instances of cash that are dropping out of the system. Much of little leaks amounts to a lot of cash in total, in some instances. So do not disregard the leaks. Not only will that preserve the cash but once you understand the leaks better, the organization will step up in efficiency and effectiveness with respect to cash preservation and delivery of value.

- Tweak the process: You will find that as you deep dive into the variances, you might want to tweak certain processes so these variances are minimized. This would generally be true for adverse variances against the budget. Seek to understand why the variance, and then understand all of the processes that occur in the background to generate activity in the account. Once you fully understand the process, then it is a matter of tweaking this to marginally or structurally change some key areas that might favorable resonate across the financials in the future.

- The Technology Play: Finally, evaluate the possibilities of exploring technology to surface issues early, automate repetitive processes, trigger alerts early on to mitigate any issues later, and provide on-demand analytics. Use technology to relieve time and assist and enable more thinking around how to improve the internal handoffs to further economic value in the organization.

All of the above relate to managing the finance and accounting organization well within its own domain. However, there is a bigger step that comes into play once one has established the blocks and that relates to corporate strategy and linking it to the continual evolution of the financial infrastructure.

The essential question that the lean finance organization has to answer is – What can the organization do so that we address every element that preserves and enhances value to the customer, and how do we eliminate all non-value added activities? This is largely a process question but it forces one to understand the key processes and identify what percentage of each process is value added to the customer vs. non-value added. This can be represented by time or cost dimension. The goal is to yield as much value added activities as possible since the underlying presumption of such activity will lead to preservation of cash and also increase cash acquisition activities from the customer.

Risk Management and Finance

If you are in finance, you are a risk manager. Say what? Risk management! Imagine being the hub in a spoke of functional areas, each of which is embedded with a risk pattern that can vary over time. A sound finance manager would be someone who would be best able to keep pulse, and be able to support the decisions that can contain the risk. Thus, value management becomes critical: Weighing the consequence of a decision against the risk that the decision poses. Not cost management, but value management. And to make value management more concrete, we turn to cash impact or rather – the discounted value of future stream of cash that may or may not be a consequent to a decision. Companies carry risks. If not, a company will not offer any premiums in value to the market. They create competitive advantage – defined as sorting a sustained growth in free cash flow as the key metric that becomes the separator.

John Kay, an eminent strategist, had identified four sources of competitive advantage: Organization Architecture and Culture, Reputation, Innovation and Strategic Assets. All of these are inextricably intertwined, and must be aligned to service value in the company. The business value approach underpins the interrelationships best. And in so doing, scenario planning emerges as a sound machination to manage risks. Understanding the profit impact of a strategy, and the capability/initiative tie-in is one of the most crucial conversations that a good finance manager could encourage in a company. Product, market and internal capabilities become the anchor points in evolving discussions. Scenario planning thus emerges in context of trends and uncertainties: a trend in patterns may open up possibilities, the latter being in the domain of uncertainty.

There are multiple methods one could use in building scenarios and engaging in fruitful risk assessment.

1.Sensitivity Assessment: Evaluate decisions in the context of the strategy’s reliance on the resilience of business conditions. Assess the various conditions in a scenario or mutually exclusive scenarios, assess a probabilistic guesstimate on success factors, and then offer simple solutions. This assessment tends to be heuristic oriented and excellent when one is dealing with few specific decisions to be made. There is an elevated sense of clarity with regard to the business conditions that may present itself. And this is most commonly used, but does not thwart the more realistic conditions where clarity is obfuscated and muddy.

2.Strategy Evaluation: Use scenarios to test a strategy by throwing a layer of interaction complexity. To the extent you can disaggregate the complexity, the evaluation of a strategy is better tenable. But once again, disaggregation has its downsides. We don’t operate in a vacuum. It is the aggregation, and negotiating through this aggregation effectively is where the real value is. You may have heard of the Mckinsey MECE (Mutually Exclusive; Comprehensively Exhaustive) methodology where strategic thrusts are disaggregated and contained within a narrow framework. The idea is that if one does that enough, one has an untrammeled confidence in choosing one initiative over another. That is true again in some cases, but my belief is that the world operates at a more synthetic level than pure analytic. We resort to analytics since it is too damned hard to synthesize, and be able to agree on an optimal solution. I am not creaming analytics; I am only suggesting that there is some possibility that a false hypothesis is accepted and a true one rejected. Thus analytics is an important tool, but must be weighed along with the synthetic tradition.

3.Synthetic Development: By far the most interesting and perhaps the most controversial with glint of academic and theoretical monstrosities included – this represents developing and broadcasting all scenarios equally weighed, and grouping interaction of scenarios. Thus, if introducing a multi-million dollar initiative in untested waters is a decision you have to weigh, one must go through the first two methods, and then review the final outcome against peripheral factors that were not introduced initially. A simple statement or realization like – The competition for Southwest is the Greyhound bus – could significantly alter the expanse of the strategy.

If you think of the new world of finance being nothing more than crunching numbers … stop and think again. Yes …crunching those numbers play a big part, less a cause than an effect of the mental model that you appropriate in this prized profession.