Category Archives: Learning Process

Managing Scale

| I think the most difficult thing had been scaling the infrastructure. Trying to support the response we had received from our users and the number of people that were interested in using the software. – Shawn Fanning |

Froude’s number? It is defined as the square of the ship’s velocity divided by its length and multiplied by the acceleration caused by gravity. So why are we introducing ships in this chapter? As I have done before, I am liberally standing on the shoulder of the giant, Geoffrey West, and borrowing from his account on the importance of the Froude’s number and the practical implications. Since ships are subject to turbulence, using a small model that works in a simulated turbulent environment might not work when we manufacture a large ship that is facing the ebbs and troughs of a finicky ocean. The workings and impact of turbulence is very complex, and at scale it becomes even more complex. Froude’s key contribution was to figure out a mathematical pathway of how to efficiently and effectively scale from a small model to a practical object. He did that by using a ratio as the common denominator. Mr. West provides an example that hits home: How fast does a 10-foot-long ship have to move to mimic the motion of a 700-foot-long ship moving at 20 knots. If they are to have the same Froude number (that is, the same value of the square of their velocity divided by their length), then the velocity has to scale as the square root of their lengths. The ratio of the square root of their lengths is the the square of 700 feet of the ship/10 feet of the model ship which turns out to be the square of 70. For the 10-foot model to mimic the motion of a large ship, it must move at the speed of 20 knots/ square of 70 or 2.5 knots. The Froude number is still widely used across many fields today to bridge small scale and large-scale thinking. Although this number applies to physical systems, the notion that adaptive systems can be similarly bridged through appropriate mathematical equations. Unfortunately, because of the increased number of variables impacting adaptive systems and all of these variables working and learning from one another, the task of establishing a Froude number becomes diminishingly small.

The other concept that has gained wide attention is the science of allometry. Allometry essentially states that as size increases, then the form of the object would change. Allometric scaling governs all complex physical and adaptive systems. So the question is whether there are some universal laws or mathematics that can be used to enable us to better understand or predict scale impacts. Let us extend this thinking a bit further. If sizes influence form and form constitute all sub-physical elements, then it would stand to reason that a universal law or a set of equations can provide deep explanatory powers on scale and systems. One needs to bear in mind that even what one might consider a universal law might be true within finite observations and boundaries. In other words, if there are observations that fall outside of those boundaries, one is forced into resetting our belief in the universal law or to frame a new paradigm to cover these exigencies. I mention this because as we seek to understand business and global grand challenges considering the existence of complexity, scale, chaos and seeming disorder – we might also want to embrace multiple laws or formulations working at different hierarchies and different data sets to arrive at satisficing solutions to the problems that we want to wrestle with.

Physics and mathematics allow a qualitatively high degree of predictability. One can craft models across different scales to make a sensible approach on how to design for scale. If you were to design a prototype using a 3D printer and decide to scale that prototype a 100X, there are mathematical scalar components that are factored into the mechanics to allow for some sort of equivalence which would ultimately lead to the final product fulfilling its functional purpose in a complex physical system. But how does one manage scale in light of those complex adaptive systems that emerge due to human interactions, evolution of organization, uncertainty of the future, and dynamic rules that could rapidly impact the direction of a company?

Is scale a single measure? Or is it a continuum? In our activities, we intentionally or unintentionally invoke scale concepts. What is the most efficient scale to measure an outcome, so we can make good policy decisions, how do we apply our learning from one scale to a system that operates on another scale and how do we assess how sets of phenomena operate at different scales, spatially and temporally, and how they impact one another? Now the most interesting question: Is scale polymorphous? Does the word scale have different meanings in different contexts? When we talk about microbiology, we are operating at micro-scales. When we talk at a very macro level, our scales are huge. In business, we regard scale with respect to how efficiently we grow. In one way, it is a measure but for the following discussion, we will interpret scale as non-linear growth expending fewer and fewer resources to support that growth as a ratio.

As we had discussed previously, complex adaptive systems self-organize over time. They arrive at some steady state outcome without active intervention. In fact, the active intervention might lead to unintended consequences that might even spell doom for the system that is being influenced. So as an organization scales, it is important to keep this notion of rapid self-organization in mind which will inform us to make or not make certain decisions from a central or top-down perspective. In other words, part of managing scale successfully is to not manage it at a coarse-grained level.

The second element of successfully managing scale is to understand the constraints that prevent scale. There is an entire chapter dedicated to the theory of constraints which sheds light on why this is a fundamental process management technique that increases the pace of the system. But for our purposes in this section, we will summarize as follows: every system as it grows have constraints. It is important to understand the constraints because these constraints slow the system: the bottlenecks have to be removed. And once one constraint is removed, then one comes across another constraint. The system is a chain of events and it is imperative that all of these events are identified. The weakest links harangue the systems and these weakest links have to be either cleared or resourced to enable the system to scale. It is a continuous process of observation and tweaking the results with the established knowledge that the demons of uncertainty and variability can reset the entire process and one might have to start again. Despite that fact, constraint management is an effective method to negotiate and manage scale.

The third element is devising the appropriate organization architecture. As one projects into the future, management might be inclined toward developing and investing in the architecture early to accommodate the scale. Overinvestment in the architecture might not be efficient. As mentioned, cities and social systems that grow 100% require 85% investment in infrastructure: in other words, systems grow on a sublinear scale from an infrastructure perspective. How does management of scale arrive at the 85%? It is nigh impossible, but it is important to reserve that concept since it informs management to architect the infrastructure cautiously. Large investments upfront could be a waste or could slow the system down: alternative, investments that are postponed a little too late can also impact the system adversely.

The fourth element of managing scale is to focus your lens of opportunity. In macroecology, we can arrive at certain conclusions when we regard the system from a distance versus very closely. We can subsume our understanding into one big bucket called climate change and then we figure out different ways to manage the complexity that causes the climate change by invoking certain policies and incentives at a macro level. However, if we go closer, we might decide to target a very specific contributor to climate change – namely, fossil fuels. The theory follows that to manage the dynamic complexity and scale of climate impact – it would be best to address a major factor which, in this case, would be fossil fuels. The equivalence of this in a natural business setting would be to establish and focus the strategy for scale in a niche vertical or a relatively narrower set of opportunities. Even though we are working in the web of complex adaptive systems, we might devise strategies to directionally manage the business within the framework of complex physical systems where we have an understanding of the slight variations of initial state and the realization that the final outcome might be broad but yet bounded for intentional management.

The final element is the management of initial states. Complex physical systems are governed by variation in initial states. Perturbation of these initial states can lead to a wide divergence of outcomes, albeit bounded within a certain frame of reference. It is difficult perhaps to gauge all the interactions that might occur from a starting point to the outcome, although we agree that a few adjustments like decentralization of decision making, constraint management, optimal organization structure and narrowing the playing field would be helpful.

Internal versus External Scale

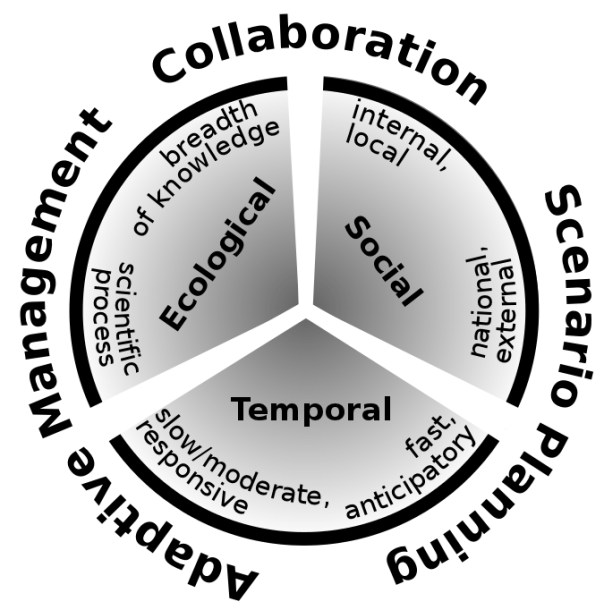

This article discusses internal and external complexity before we tee up a more detailed discussion on internal versus external scale. This chapter acknowledges that complex adaptive systems have inherent internal and external complexities which are not additive. The impact of these complexities is exponential. Hence, we have to sift through our understanding and perhaps even review the salient aspects of complexity science which have already been covered in relatively more detail in earlier chapter. However, revisiting complexity science is important, and we will often revisit this across other blog posts to really hit home the fundamental concepts and its practical implications as it relates to management and solving challenges at a business or even a grander social scale.

A complex system is a part of a larger environment. It is a safe to say that the larger environment is more complex than the system itself. But for the complex system to work, it needs to depend upon a certain level of predictability and regularity between the impact of initial state and the events associated with it or the interaction of the variables in the system itself. Note that I am covering both – complex physical systems and complex adaptive systems in this discussion. A system within an environment has an important attribute: it serves as a receptor to signals of external variables of the environment that impact the system. The system will either process that signal or discard the signal which is largely based on what the system is trying to achieve. We will dedicate an entire article on system engineering and thinking later, but the uber point is that a system exists to serve a definite purpose. All systems are dependent on resources and exhibits a certain capacity to process information. Hence, a system will try to extract as many regularities as possible to enable a predictable dynamic in an efficient manner to fulfill its higher-level purpose.

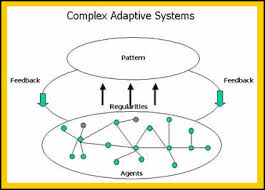

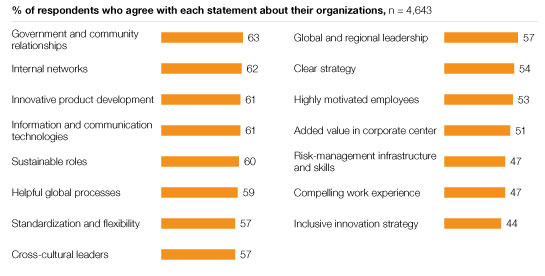

Let us understand external complexities. We can interchangeably use the word environmental complexity as well. External complexity represents physical, cultural, social, and technological elements that are intertwined. These environments beleaguered with its own grades of complexity acts as a mold to affect operating systems that are mere artifacts. If operating systems can fit well within the mold, then there is a measure of fitness or harmony that arises between an internal complexity and external complexity. This is the root of dynamic adaptation. When external environments are very complex, that means that there are a lot of variables at play and thus, an internal system has to process more information in order to survive. So how the internal system will react to external systems is important and they key bridge between those two systems is in learning. Does the system learn and improve outcomes on account of continuous learning and does it continually modify its existing form and functional objectives as it learns from external complexity? How is the feedback loop monitored and managed when one deals with internal and external complexities? The environment generates random problems and challenges and the internal system has to accept or discard these problems and then establish a process to distribute the problems among its agents to efficiently solve those problems that it hopes to solve for. There is always a mechanism at work which tries to align the internal complexity with external complexity since it is widely believed that the ability to efficiently align the systems is the key to maintaining a relatively competitive edge or intentionally making progress in solving a set of important challenges.

Internal complexity are sub-elements that interact and are constituents of a system that resides within the larger context of an external complex system or the environment. Internal complexity arises based on the number of variables in the system, the hierarchical complexity of the variables, the internal capabilities of information pass-through between the levels and the variables, and finally how it learns from the external environment. There are five dimensions of complexity: interdependence, diversity of system elements, unpredictability and ambiguity, the rate of dynamic mobility and adaptability, and the capability of the agents to process information and their individual channel capacities.

If we are discussing scale management, we need to ask a fundamental question. What is scale in the context of complex systems? Why do we manage for scale? How does management for scale advance us toward a meaningful outcome? How does scale compute in internal and external complex systems? What do we expect to see if we have managed for scale well? What does the future bode for us if we assume that we have optimized for scale and that is the key objective function that we have to pursue?

Model Thinking

| Model Framework |

The fundamental tenet of theory is the concept of “empiria“. Empiria refers to our observations. Based on observations, scientists and researchers posit a theory – it is part of scientific realism.

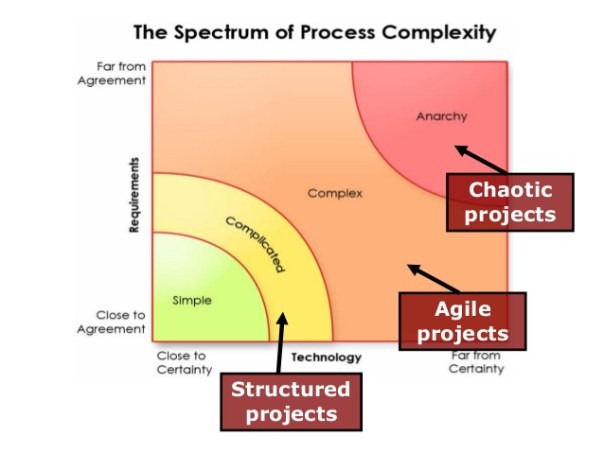

A scientific model is a causal explanation of how variables interact to produce a phenomenon, usually linearly organized. A model is a simplified map consisting of a few, primary variables that is gauged to have the most explanatory powers for the phenomenon being observed. We discussed Complex Physical Systems and Complex Adaptive Systems early on this chapter. It is relatively easier to map CPS to models than CAS, largely because models become very unwieldy as it starts to internalize more variables and if those variables have volumes of interaction between them. A simple analogy would be the use of multiple regression models: when you have a number of independent variables that interact strongly between each other, autocorrelation errors occur, and the model is not stable or does not have predictive value.

Research projects generally tend to either look at a case study or alternatively, they might describe a number of similar cases that are logically grouped together. Constructing a simple model that can be general and applied to many instances is difficult, if not impossible. Variables are subject to a researcher’s lack of understanding of the variable or the volatility of the variable. What further accentuates the problem is that the researcher misses on the interaction of how the variables play against one another and the resultant impact on the system. Thus, our understanding of our system can be done through some sort of model mechanics but, yet we share the common belief that the task of building out a model to provide all of the explanatory answers are difficult, if not impossible. Despite our understanding of our limitations of modeling, we still develop frameworks and artifact models because we sense in it a tool or set of indispensable tools to transmit the results of research to practical use cases. We boldly generalize our findings from empiria into general models that we hope will explain empiria best. And let us be mindful that it is possible – more so in the CAS systems than CPS that we might have multiple models that would fight over their explanatory powers simply because of the vagaries of uncertainty and stochastic variations.

Popper says: “Science does not rest upon rock-bottom. The bold structure of its theories rises, as it were, above a swamp. It is like a building erected on piles. The piles are driven down from above into the swamp, but not down to any natural or ‘given’ base; and when we cease our attempts to drive our piles into a deeper layer, it is not because we have reached firm ground. We simply stop when we are satisfied that they are firm enough to carry the structure, at least for the time being”. This leads to the satisficing solution: if a model can choose the least number of variables to explain the greatest amount of variations, the model is relatively better than other models that would select more variables to explain the same. In addition, there is always a cost-benefit analysis to be taken into consideration: if we add x number of variables to explain variation in the outcome but it is not meaningfully different than variables less than x, then one would want to fall back on the less-variable model because it is less costly to maintain.

Researchers must address three key elements in the model: time, variation and uncertainty. How do we craft a model which reflects the impact of time on the variables and the outcome? How to present variations in the model? Different variables might vary differently independent of one another. How do we present the deviation of the data in a parlance that allows us to make meaningful conclusions regarding the impact of the variations on the outcome? Finally, does the data that is being considered are actual or proxy data? Are the observations approximate? How do we thus draw the model to incorporate the fuzziness: would confidence intervals on the findings be good enough?

Two other equally other concepts in model design is important: Descriptive Modeling and Normative Modeling.

Descriptive models aim to explain the phenomenon. It is bounded by that goal and that goal only.

There are certain types of explanations that they fall back on: explain by looking at data from the past and attempting to draw a cause and effect relationship. If the researcher is able to draw a complete cause and effect relationship that meets the test of time and independent tests to replicate the results, then the causality turns into law for the limited use-case or the phenomenon being explained. Another explanation method is to draw upon context: explaining a phenomenon by looking at the function that the activity fulfills in its context. For example, a dog barks at a stranger to secure its territory and protect the home. The third and more interesting type of explanation is generally called intentional explanation: the variables work together to serve a specific purpose and the researcher determines that purpose and thus, reverse engineers the understanding of the phenomenon by understanding the purpose and how the variables conform to achieve that purpose.

This last element also leads us to thinking through the other method of modeling – namely, normative modeling. Normative modeling differs from descriptive modeling because the target is not to simply just gather facts to explain a phenomenon, but rather to figure out how to improve or change the phenomenon toward a desirable state. The challenge, as you might have already perceived, is that the subjective shadow looms high and long and the ultimate finding in what would be a normative model could essentially be a teleological representation or self-fulfilling prophecy of the researcher in action. While this is relatively more welcome in a descriptive world since subjectivism is diffused among a larger group that yields one solution, it is not the best in a normative world since variation of opinions that reflect biases can pose a problem.

How do we create a representative model of a phenomenon? First, we weigh if the phenomenon is to be understood as a mere explanation or to extend it to incorporate our normative spin on the phenomenon itself. It is often the case that we might have to craft different models and then weigh one against the other that best represents how the model can be explained. Some of the methods are fairly simple as in bringing diverse opinions to a table and then agreeing upon one specific model. The advantage of such an approach is that it provides a degree of objectivism in the model – at least in so far as it removes the divergent subjectivity that weaves into the various models. Other alternative is to do value analysis which is a mathematical method where the selection of the model is carried out in stages. You define the criteria of the selection and then the importance of the goal (if that be a normative model). Once all of the participants have a general agreement, then you have the makings of a model. The final method is to incorporate all all of the outliers and the data points in the phenomenon that the model seeks to explain and then offer a shared belief into those salient features in the model that would be best to apply to gain information of the phenomenon in a predictable manner.

There are various languages that are used for modeling:

Written Language refers to the natural language description of the model. If price of butter goes up, the quantity demanded of the butter will go down. Written language models can be used effectively to inform all of the other types of models that follow below. It often goes by the name of “qualitative” research, although we find that a bit limiting. Just a simple statement like – This model approximately reflects the behavior of people living in a dense environment …” could qualify as a written language model that seeks to shed light on the object being studied.

Icon Models refer to a pictorial representation and probably the earliest form of model making. It seeks to only qualify those contours or shapes or colors that are most interesting and relevant to the object being studied. The idea of icon models is to pictorially abstract the main elements to provide a working understanding of the object being studied.

Topological Models refer to how the variables are placed with respect to one another and thus helps in creating a classification or taxonomy of the model. Once can have logical trees, class trees, Venn diagrams, and other imaginative pictorial representation of fields to further shed light on the object being studied. In fact, pictorial representations must abide by constant scale, direction and placements. In other words, if the variables are placed on a different scale on different maps, it would be hard to draw logical conclusions by sight alone. In addition, if the placements are at different axis in different maps or have different vectors, it is hard to make comparisons and arrive at a shared consensus and a logical end result.

Arithmetic Models are what we generally fall back on most. The data is measured with an arithmetic scale. It is done via tables, equations or flow diagrams. The nice thing about arithmetic models is that you can show multiple dimensions which is not possible with other modeling languages. Hence, the robustness and the general applicability of such models are huge and thus is widely used as a key language to modeling.

Analogous Models refer to crafting explanations using the power of analogy. For example, when we talk about waves – we could be talking of light waves, radio waves, historical waves, etc. These metaphoric representations can be used to explain phenomenon, but at best, the explanatory power is nebulous, and it would be difficult to explain the variations and uncertainties between two analogous models. However, it still is used to transmit information quickly through verbal expressions like – “Similarly”, “Equivalently”, “Looks like ..” etc. In fact, extrapolation is a widely used method in modeling and we would ascertain this as part of the analogous model to a great extent. That is because we time-box the variables in the analogous model to one instance and the extrapolated model to another instance and we tie them up with mathematical equations.

Building a Lean Financial Infrastructure!

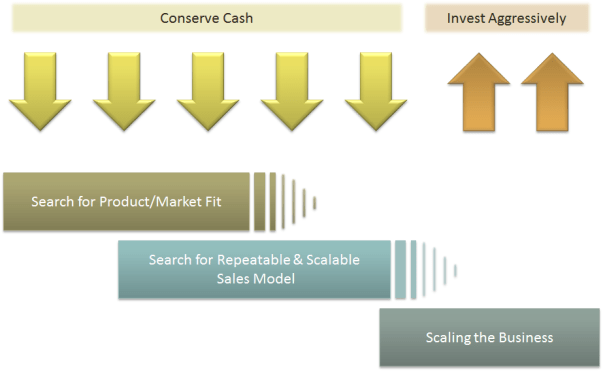

A lean financial infrastructure presumes the ability of every element in the value chain to preserve and generate cash flow. That is the fundamental essence of the lean infrastructure that I espouse. So what are the key elements that constitute a lean financial infrastructure?

And given the elements, what are the key tweaks that one must continually make to ensure that the infrastructure does not fall into entropy and the gains that are made fall flat or decay over time. Identification of the blocks and monitoring and making rapid changes go hand in hand.

The Key Elements or the building blocks of a lean finance organization are as follows:

- Chart of Accounts: This is the critical unit that defines the starting point of the organization. It relays and groups all of the key economic activities of the organization into a larger body of elements like revenue, expenses, assets, liabilities and equity. Granularity of these activities might lead to a fairly extensive chart of account and require more work to manage and monitor these accounts, thus requiring incrementally a larger investment in terms of time and effort. However, the benefits of granularity far exceeds the costs because it forces management to look at every element of the business.

- The Operational Budget: Every year, organizations formulate the operational budget. That is generally a bottoms up rollup at a granular level that would map to the Chart of Accounts. It might follow a top-down directive around what the organization wants to land with respect to income, expense, balance sheet ratios, et al. Hence, there is almost always a process of iteration in this step to finally arrive and lock down the Budget. Be mindful though that there are feeders into the budget that might relate to customers, sales, operational metrics targets, etc. which are part of building a robust operational budget.

- The Deep Dive into Variances: As you progress through the year and part of the monthly closing process, one would inquire about how the actual performance is tracking against the budget. Since the budget has been done at a granular level and mapped exactly to the Chart of Accounts, it thus becomes easier to understand and delve into the variances. Be mindful that every element of the Chart of Account must be evaluated. The general inclination is to focus on the large items or large variances, while skipping the small expenses and smaller variances. That method, while efficient, might not be effective in the long run to build a lean finance organization. The rule, in my opinion, is that every account has to be looked and the question should be – Why? If the management has agreed on a number in the budget, then why are the actuals trending differently. Could it have been the budget and that we missed something critical in that process? Or has there been a change in the underlying economics of the business or a change in activities that might be leading to these “unexpected variances”. One has to take a scalpel to both – favorable and unfavorable variances since one can learn a lot about the underlying drivers. It might lead to managerially doing more of the better and less of the worse. Furthermore, this is also a great way to monitor leaks in the organization. Leaks are instances of cash that are dropping out of the system. Much of little leaks amounts to a lot of cash in total, in some instances. So do not disregard the leaks. Not only will that preserve the cash but once you understand the leaks better, the organization will step up in efficiency and effectiveness with respect to cash preservation and delivery of value.

- Tweak the process: You will find that as you deep dive into the variances, you might want to tweak certain processes so these variances are minimized. This would generally be true for adverse variances against the budget. Seek to understand why the variance, and then understand all of the processes that occur in the background to generate activity in the account. Once you fully understand the process, then it is a matter of tweaking this to marginally or structurally change some key areas that might favorable resonate across the financials in the future.

- The Technology Play: Finally, evaluate the possibilities of exploring technology to surface issues early, automate repetitive processes, trigger alerts early on to mitigate any issues later, and provide on-demand analytics. Use technology to relieve time and assist and enable more thinking around how to improve the internal handoffs to further economic value in the organization.

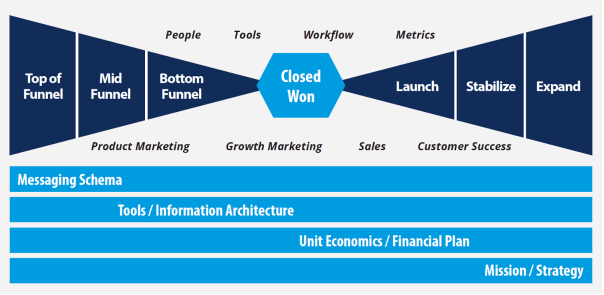

All of the above relate to managing the finance and accounting organization well within its own domain. However, there is a bigger step that comes into play once one has established the blocks and that relates to corporate strategy and linking it to the continual evolution of the financial infrastructure.

The essential question that the lean finance organization has to answer is – What can the organization do so that we address every element that preserves and enhances value to the customer, and how do we eliminate all non-value added activities? This is largely a process question but it forces one to understand the key processes and identify what percentage of each process is value added to the customer vs. non-value added. This can be represented by time or cost dimension. The goal is to yield as much value added activities as possible since the underlying presumption of such activity will lead to preservation of cash and also increase cash acquisition activities from the customer.