Category Archives: Learning Process

The Finance Playbook for Scaling Complexity Without Chaos

From Controlled Growth to Operational Grace

Somewhere between Series A optimism and Series D pressure sits the very real challenge of scale. Not just growth for its own sake but growth with control, precision, and purpose. A well-run finance function becomes less about keeping the lights on and more about lighting the runway. I have seen it repeatedly. You can double ARR, but if your deal desk, revenue operations, or quote-to-cash processes are even slightly out of step, you are scaling chaos, not a company.

Finance does not scale with spreadsheets and heroics. It scales with clarity. With every dollar, every headcount, and every workflow needing to be justified in terms of scale, simplicity must be the goal. I recall sitting in a boardroom where the CEO proudly announced a doubling of the top line. But it came at the cost of three overlapping CPQ systems, elongated sales cycles, rogue discounting, and a pipeline no one trusted. We did not have a scale problem. We had a complexity problem disguised as growth.

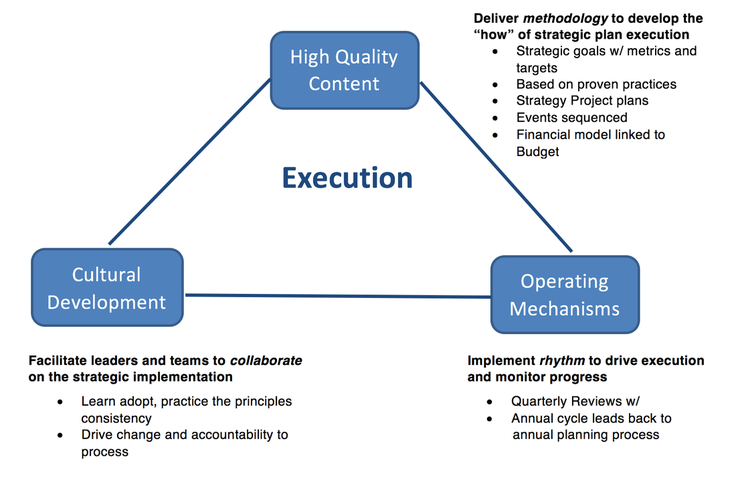

OKRs Are Not Just for Product Teams

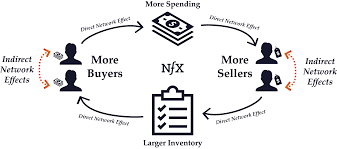

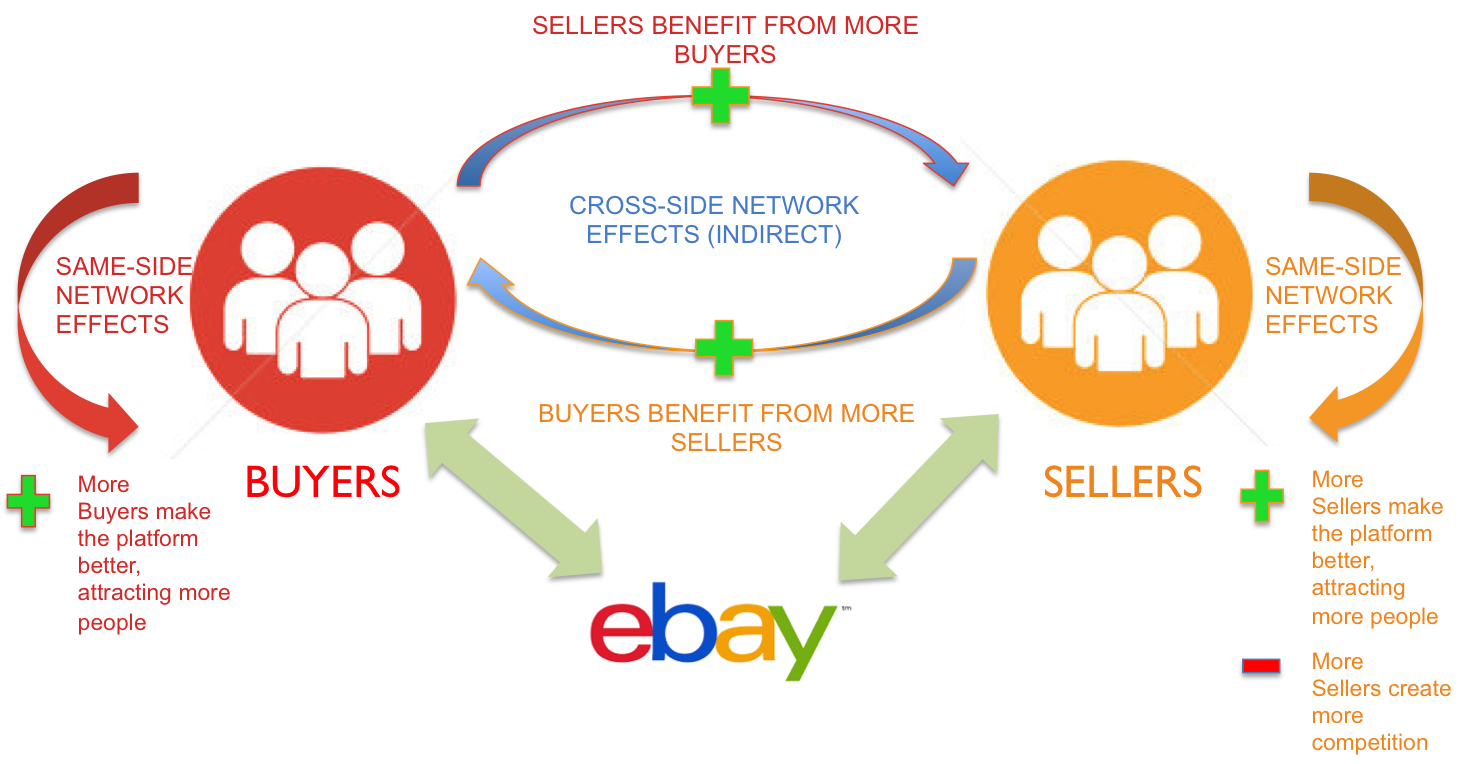

When finance is integrated into company OKRs, magic happens. We begin aligning incentives across sales, legal, product, and customer success teams. Suddenly, the sales operations team is not just counting bookings but shaping them. Deal desk isn’t just a speed bump before legal review, but a value architect. Our quote-to-cash process is no longer a ticketing system but a flywheel for margin expansion.

At a Series B company, their shift began by tying financial metrics directly to the revenue team’s OKRs. Quota retirement was not enough. They measured the booked gross margin. Customer acquisition cost. Implementation of velocity. The sales team was initially skeptical but soon began asking more insightful questions. Deals that initially appeared promising were flagged early. Others that seemed too complicated were simplified before they even reached RevOps. Revenue is often seen as art. But finance gives it rhythm.

Scaling Complexity Despite the Chaos

The truth is that chaos is not the enemy of scale. Chaos is the cost of momentum. Every startup that is truly growing at a pace inevitably creates complexity. Systems become tangled. Roles blur. Approvals drift. That is not failure. That is physics. What separates successful companies is not the absence of chaos but their ability to organize it.

I often compare this to managing a growing city. You do not stop new buildings from going up just because traffic worsens. You introduce traffic lights, zoning laws, and transit systems that support the growth. In finance, that means being ready to evolve processes as soon as growth introduces friction. It means designing modular systems where complexity is absorbed rather than resisted. You do not simplify the growth. You streamline the experience of growing. Read Scale by Geoffrey West. Much of my interest in complexity theory and architecture for scale comes from it. Also, look out for my book, which will be published in February 2026: Complexity and Scale: Managing Order from Chaos. This book aligns literature in complexity theory with the microeconomics of scaling vectors and enterprise architecture.

At a late-stage Series C company, the sales motion had shifted from land-and-expand to enterprise deals with multi-year terms and custom payment structures. The CPQ tool was unable to keep up. Rather than immediately overhauling the tool, they developed middleware logic that routed high-complexity deals through a streamlined approval process, while allowing low-risk deals to proceed unimpeded. The system scaled without slowing. Complexity still existed, but it no longer dictated pace.

Cash Discipline: The Ultimate Growth KPI

Cash is not just oxygen. It is alignment. When finance speaks early and often about burn efficiency, marginal unit economics, and working capital velocity, we move from gatekeepers to enablers. I often remind founders that the cost of sales is not just the commission plan. It’s in the way deals are structured. It’s in how fast a contract can be approved. It’s in how many hands a quote needs to pass through.

At one Series A professional services firm, they introduced a “Deal ROI Calculator” at the deal desk. It calculated not just price and term but implementation effort, support burden, and payback period. The result was staggering. Win rates remained stable, but average deal profitability increased by 17 percent. Sales teams began choosing deals differently. Finance was not saying no. It was saying, “Say yes, but smarter.”

Velocity is a Decision, Not a Circumstance

The best-run companies are not faster because they have fewer meetings. They are faster because decisions are closer to the data. Finance’s job is to put insight into the hands of those making the call. The goal is not to make perfect decisions. It is to make the best decision possible with the available data and revisit it quickly.

In one post-Series A firm, we embedded finance analysts inside revenue operations. It blurred the traditional lines but sped up decision-making. Discount approvals have been reduced from 48 hours to 12-24 hours. Pricing strategies became iterative. A finance analyst co-piloted the forecast and flagged gaps weeks earlier than our CRM did. It wasn’t about more control. It was about more confidence.

When Process Feels Like Progress

It is tempting to think that structure slows things down. However, the right QTC design can unlock margin, trust, and speed simultaneously. Imagine a deal desk that empowers sales to configure deals within prudent guardrails. Or a contract management workflow that automatically flags legal risks. These are not dreams. These are the functions we have implemented.

The companies that scale well are not perfect. But their finance teams understand that complexity compounds quietly. And so, we design our systems not to prevent chaos but to make good decisions routine. We don’t wait for the fire drill. We design out the fire.

Make Your Revenue Operations Your Secret Weapon

If your finance team still views sales operations as a reporting function, you are underutilizing a strategic lever. Revenue operations, when empowered, can close the gap between bookings and billings. They can forecast with precision. They can flag incentive misalignment. One of the best RevOps leaders I worked with used to say, “I don’t run reports. I run clarity.” That clarity was worth more than any point solution we bought.

In scaling environments, automation is not optional. But automation alone does not save a broken process. Finance must own the blueprint. Every system, from CRM to CPQ to ERP, must speak the same language. Data fragmentation is not just annoying. It is value-destructive.

What Should You Do Now?

Ask yourself: Does finance have visibility into every step of the revenue funnel? Do our QTC processes support strategic flexibility? Is our deal desk a source of friction or a source of enablement? Can our sales comp plan be audited and justified in a board meeting without flinching?

These are not theoretical. They are the difference between Series C confusion and Series D confidence.

Let’s Make This Personal

I have seen incredible operators get buried under process debt because they mistook motion for progress. I have seen lean finance teams punch above their weight because they anchored their operating model in OKRs, cash efficiency, and rapid decision cycles. I have also seen the opposite. A sales ops function sitting in the corner. A deal desk no one trusts. A QTC process where no one knows who owns what.

These are fixable. But only if finance decides to lead. Not just report.

So here is my invitation. If you are a CFO, a CRO, a GC, or a CEO reading this, take one day this quarter to walk your revenue path from lead to cash. Sit with the people who feel the friction. Map the handoffs. And then ask, is this how we scale with control? Do you have the right processes in place? Do you have the technology to activate the process and minimize the friction?

Precision at Scale: How to Grow Without Drowning in Complexity

In business, as in life, scale is seductive. It promises more of the good things—revenue, reach, relevance. But it also invites something less welcome: complexity. And the thing about complexity is that it doesn’t ask for permission before showing up. It simply arrives, unannounced, and tends to stay longer than you’d like.

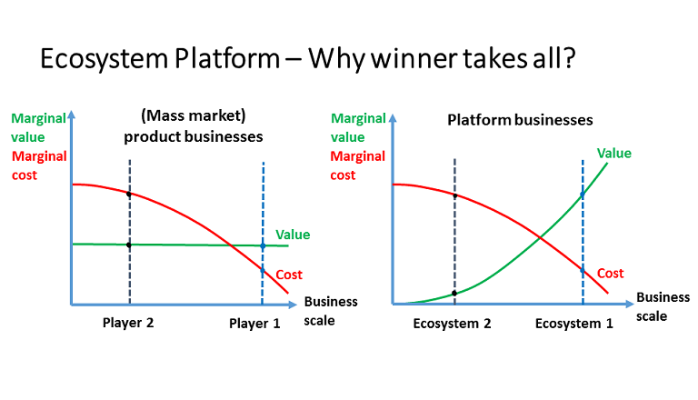

As we pursue scale, whether by growing teams, expanding into new markets, or launching adjacent product lines, we must ask a question that seems deceptively simple: how do we know we’re scaling the right way? That question is not just philosophical—it’s deeply economic. The right kind of scale brings leverage. The wrong kind brings entropy.

Now, if I’ve learned anything from years of allocating capital, it is this: returns come not just from growth, but from managing the cost and coordination required to sustain that growth. In fact, the most successful enterprises I’ve seen are not the ones that scaled fastest. They’re the ones that scaled precisely. So, let’s get into how one can scale thoughtfully, without overinvesting in capacity, and how to tell when the system you’ve built is either flourishing or faltering.

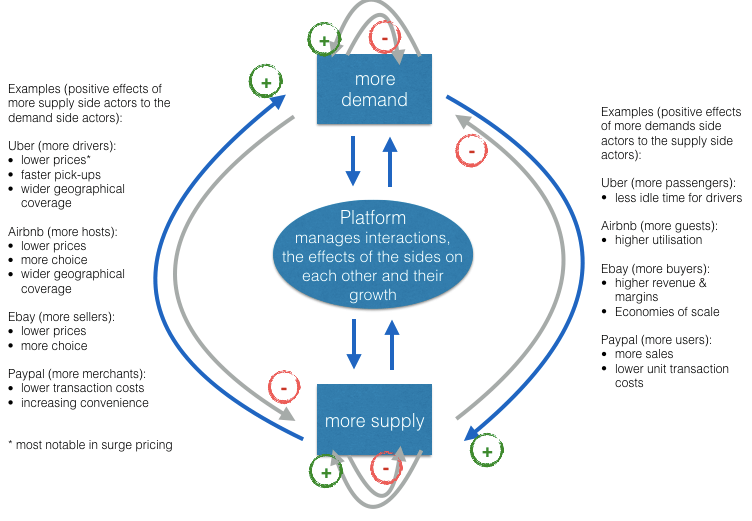

To begin, one must understand that scale and complexity do not rise in parallel; complexity has a nasty habit of accelerating. A company with two teams might have a handful of communication lines. Add a third team, and you don’t just add more conversations—you add relationships between every new and existing piece. In engineering terms, it’s a combinatorial explosion. In business terms, it’s meetings, misalignment, and missed expectations.

Cities provide a useful analogy. When they grow in population, certain efficiencies appear. Infrastructure per person often decreases, creating cost advantages. But cities also face nonlinear rises in crime, traffic, and disease—all manifestations of unmanaged complexity. The same is true in organizations. The system pays a tax for every additional node, whether that’s a service, a process, or a person. That tax is complexity, and it compounds.

Knowing this, we must invest in capacity like we would invest in capital markets—with restraint and foresight. Most failures in capacity planning stem from either a lack of preparation or an excess of confidence. The goal is to invest not when systems are already breaking, but just before the cracks form. And crucially, to invest no more than necessary to avoid those cracks.

Now, how do we avoid overshooting? I’ve found that the best approach is to treat capacity like runway. You want enough of it to support takeoff, but not so much that you’ve spent your fuel on unused pavement. We achieve this by investing in increments, triggered by observable thresholds. These thresholds should be quantitative and predictive—not merely anecdotal. If your servers are running at 85 percent utilization across sustained peak windows, that might justify additional infrastructure. If your engineering lead time starts rising despite team growth, it suggests friction has entered the system. Either way, what you’re watching for is not growth alone, but whether the system continues to behave elegantly under that growth.

Elegance matters. Systems that age well are modular, not monolithic. In software, this might mean microservices that scale independently. In operations, it might mean regional pods that carry their own load, instead of relying on a centralized command. Modular systems permit what I call “selective scaling”—adding capacity where needed, without inflating everything else. It’s like building a house where you can add another bedroom without having to reinforce the foundation. That kind of flexibility is worth gold.

Of course, any good decision needs a reliable forecast behind it. But forecasting is not about nailing the future to a decimal point. It is about bounding uncertainty. When evaluating whether to scale, I prefer forecasts that offer a range—base, best, and worst-case scenarios—and then tie investment decisions to the 75th percentile of demand. This ensures you’re covering plausible upside without betting on the moon.

Let’s not forget, however, that systems are only as good as the signals they emit. I’m wary of organizations that rely solely on lagging indicators like revenue or margin. These are important, but they are often the last to move. Leading indicators—cycle time, error rates, customer friction, engineer throughput—tell you much sooner whether your system is straining. In fact, I would argue that latency, broadly defined, is one of the clearest signs of stress. Latency in delivery. Latency in decisions. Latency in feedback. These are the early whispers before systems start to crack.

To measure whether we’re making good decisions, we need to ask not just if outcomes are improving, but if the effort to achieve them is becoming more predictable. Systems with high variability are harder to scale because they demand constant oversight. That’s a recipe for executive burnout and organizational drift. On the other hand, systems that produce consistent results with declining variance signal that the business is not just growing—it’s maturing.

Still, even the best forecasts and the finest metrics won’t help if you lack the discipline to say no. I’ve often told my teams that the most underrated skill in growth is the ability to stop. Stopping doesn’t mean failure; it means the wisdom to avoid doubling down when the signals aren’t there. This is where board oversight matters. Just as we wouldn’t pour more capital into an underperforming asset without a turn-around plan, we shouldn’t scale systems that aren’t showing clear returns.

So when do we stop? There are a few flags I look for. The first is what I call capacity waste—resources allocated but underused, like a datacenter running at 20 percent utilization, or a support team waiting for tickets that never come. That’s not readiness. That’s idle cost. The second flag is declining quality. If error rates, customer complaints, or rework spike following a scale-up, then your complexity is outpacing your coordination. Third, I pay attention to cognitive load. When decision-making becomes a game of email chains and meeting marathons, it’s time to question whether you’ve created a machine that’s too complicated to steer.

There’s also the budget creep test. If your capacity spending increases by more than 10 percent quarter over quarter without corresponding growth in throughput, you’re not scaling—you’re inflating. And in inflation, as in business, value gets diluted.

One way to guard against this is by treating architectural reserves like financial ones. You wouldn’t deploy your full cash reserve just because an opportunity looks interesting. You’d wait for evidence. Similarly, system buffers should be sized relative to forecast volatility, not organizational ambition. A modest buffer is prudent. An oversized one is expensive insurance.

Some companies fall into the trap of building for the market they hope to serve, not the one they actually have. They build as if the future were guaranteed. But the future rarely offers such certainty. A better strategy is to let the market pull capacity from you. When customers stretch your systems, then you invest. Not because it’s a bet, but because it’s a reaction to real demand.

There’s a final point worth making here. Scaling decisions are not one-time events. They are sequences of bets, each informed by updated evidence. You must remain agile enough to revise the plan. Quarterly evaluations, architectural reviews, and scenario testing are the boardroom equivalent of course correction. Just as pilots adjust mid-flight, companies must recalibrate as assumptions evolve.

To bring this down to earth, let me share a brief story. A fintech platform I advised once found itself growing at 80 percent quarter over quarter. Flush with success, they expanded their server infrastructure by 200 percent in a single quarter. For a while, it worked. But then something odd happened. Performance didn’t improve. Latency rose. Error rates jumped. Why? Because they hadn’t scaled the right parts. The orchestration layer, not the compute layer, was the bottleneck. Their added capacity actually increased system complexity without solving the real issue. It took a re-architecture, and six months of disciplined rework, to get things back on track. The lesson: scaling the wrong node is worse than not scaling at all.

In conclusion, scale is not the enemy. But ungoverned scale is. The real challenge is not growth, but precision. Knowing when to add, where to reinforce, and—perhaps most crucially—when to stop. If we build systems with care, monitor them with discipline, and remain intellectually honest about what’s working, we give ourselves the best chance to grow not just bigger, but better.

And that, to borrow a phrase from capital markets, is how you compound wisely.

Bias and Error: Human and Organizational Tradeoff

“I spent a lifetime trying to avoid my own mental biases. A.) I rub my own nose into my own mistakes. B.) I try and keep it simple and fundamental as much as I can. And, I like the engineering concept of a margin of safety. I’m a very blocking and tackling kind of thinker. I just try to avoid being stupid. I have a way of handling a lot of problems — I put them in what I call my ‘too hard pile,’ and just leave them there. I’m not trying to succeed in my ‘too hard pile.’” : Charlie Munger — 2020 CalTech Distinguished Alumni Award interview

Bias is a disproportionate weight in favor of or against an idea or thing, usually in a way that is closed-minded, prejudicial, or unfair. Biases can be innate or learned. People may develop biases for or against an individual, a group, or a belief. In science and engineering, a bias is a systematic error. Statistical bias results from an unfair sampling of a population, or from an estimation process that does not give accurate results on average.

Error refers to a outcome that is different from reality within the context of the objective function that is being pursued.

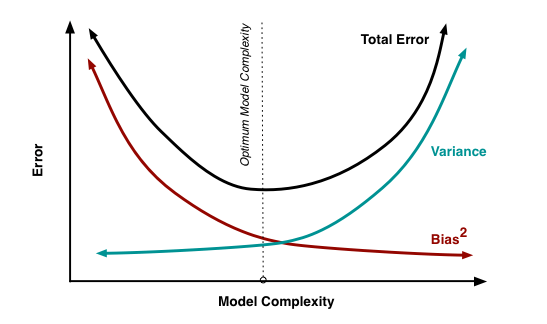

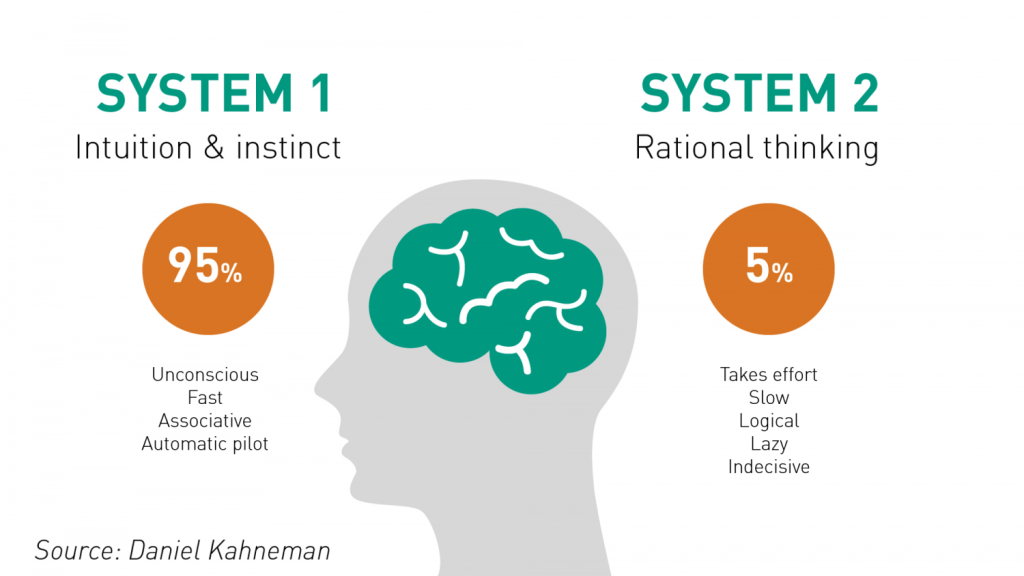

Thus, I would like to think that the Bias is a process that might lead to an Error. However, that is not always the case. There are instances where a bias might get you to an accurate or close to an accurate result. Is having a biased framework always a bad thing? That is not always the case. From an evolutionary standpoint, humans have progressed along the dimension of making rapid judgements – and much of them stemming from experience and their exposure to elements in society. Rapid judgements are typified under the System 1 judgement (Kahneman, Tversky) which allows bias and heuristic to commingle to effectively arrive at intuitive decision outcomes.

And again, the decision framework constitutes a continually active process in how humans or/and organizations execute upon their goals. It is largely an emotional response but could just as well be an automated response to a certain stimulus. However, there is a danger prevalent in System 1 thinking: it might lead one to comfortably head toward an outcome that is seemingly intuitive, but the actual result might be significantly different and that would lead to an error in the judgement. In math, you often hear the problem of induction which establishes that your understanding of a future outcome relies on the continuity of the past outcomes, and that is an errant way of thinking although it still represents a useful tool for us to advance toward solutions.

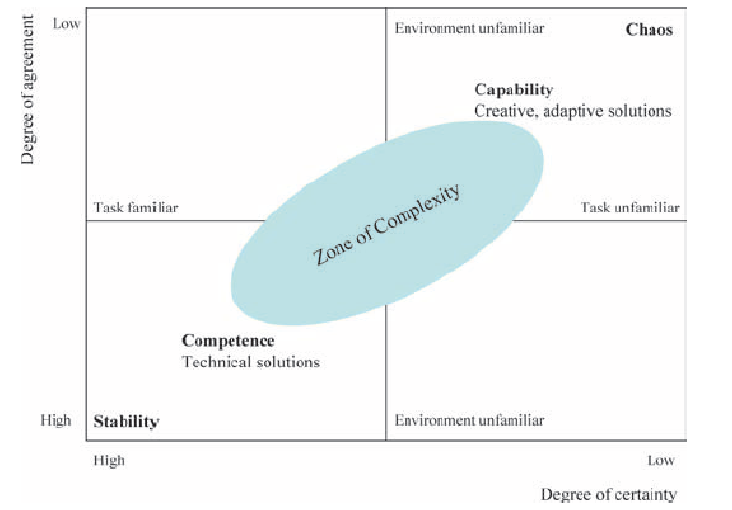

System 2 judgement emerges as another means to temper the more significant variabilities associated with System 1 thinking. System 2 thinking represents a more deliberate approach which leads to a more careful construct of rationale and thought. It is a system that slows down the decision making since it explores the logic, the assumptions, and how the framework tightly fits together to test contexts. There are a more lot more things at work wherein the person or the organization has to invest the time, focus the efforts and amplify the concentration around the problem that has to be wrestled with. This is also the process where you search for biases that might be at play and be able to minimize or remove that altogether. Thus, each of the two Systems judgement represents two different patterns of thinking: rapid, more variable and more error prone outcomes vs. slow, stable and less error prone outcomes.

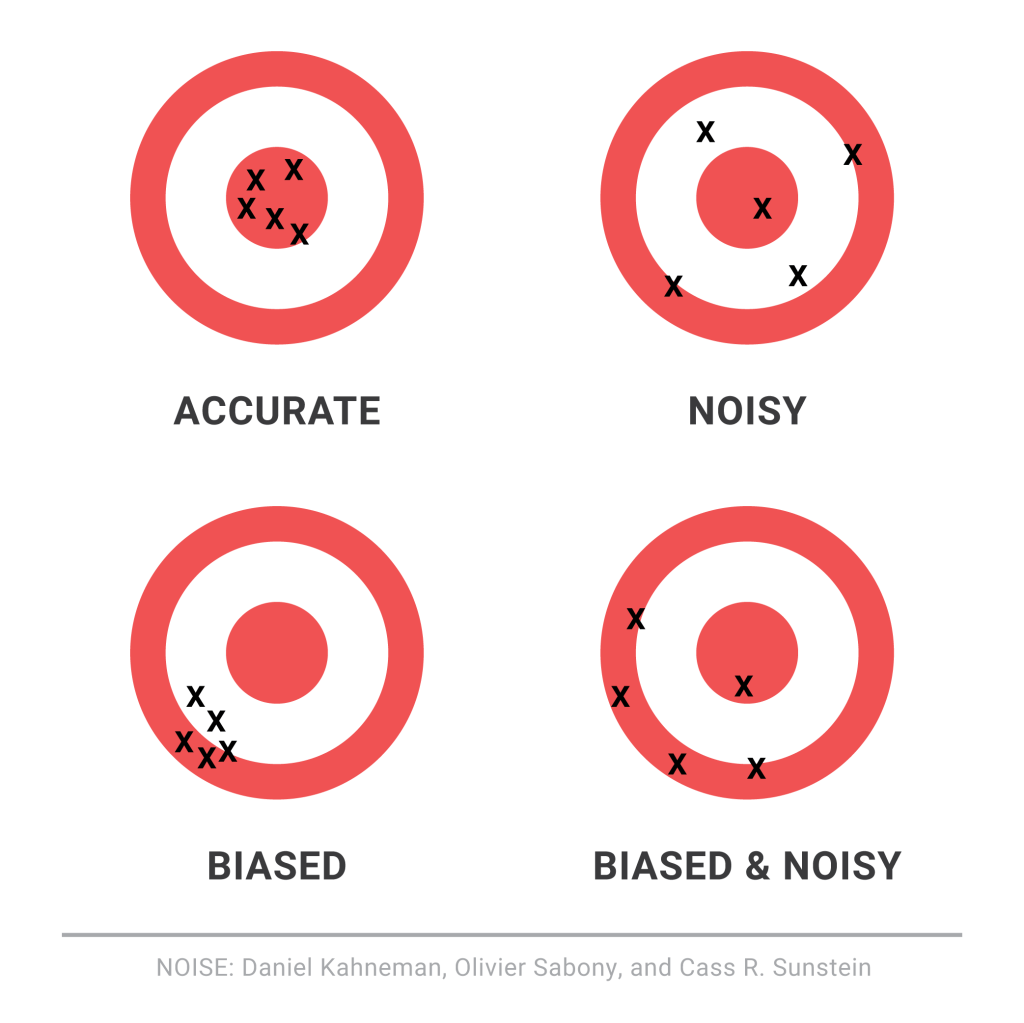

So let us revisit the Bias vs. Variance tradeoff. The idea is that the more bias you bring to address a problem, there is less variance in the aggregate. That does not mean that you are accurate. It only means that there is less variance in the set of outcomes, even if all of the outcomes are materially wrong. But it limits the variance since the bias enforces a constraint in the hypotheses space leading to a smaller and closely knit set of probabilistic outcomes. If you were to remove the constraints in the hypotheses space – namely, you remove bias in the decision framework – well, you are faced with a significant number of possibilities that would result in a larger spread of outcomes. With that said, the expected value of those outcomes might actually be closer to reality, despite the variance – than a framework decided upon by applying heuristic or operating in a bias mode.

So how do we decide then? Jeff Bezos had mentioned something that I recall: some decisions are one-way street and some are two-way. In other words, there are some decisions that cannot be undone, for good or for bad. It is a wise man who is able to anticipate that early on to decide what system one needs to pursue. An organization makes a few big and important decisions, and a lot of small decisions. Identify the big ones and spend oodles of time and encourage a diverse set of input to work through those decisions at a sufficiently high level of detail. When I personally craft rolling operating models, it serves a strategic purpose that might sit on shifting sands. That is perfectly okay! But it is critical to evaluate those big decisions since the crux of the effectiveness of the strategy and its concomitant quantitative representation rests upon those big decisions. Cutting corners can lead to disaster or an unforgiving result!

I will focus on the big whale decisions now. I will assume, for the sake of expediency, that the series of small decisions, in the aggregate or by itself, will not sufficiently be large enough that it would take us over the precipice. (It is also important however to examine the possibility that a series of small decisions can lead to a more holistic unintended emergent outcome that might have a whale effect: we come across that in complexity theory that I have already touched on in a set of previous articles).

Cognitive Biases are the biggest mea culpas that one needs to worry about. Some of the more common biases are confirmation bias, attribution bias, the halo effect, the rule of anchoring, the framing of the problem, and status quo bias. There are other cognition biases at play, but the ones listed above are common in planning and execution. It is imperative that these biases be forcibly peeled off while formulating a strategy toward problem solving.

But then there are also the statistical biases that one needs to be wary of. How we select data or selection bias plays a big role in validating information. In fact, if there are underlying statistical biases, the validity of the information is questionable. Then there are other strains of statistical biases: the forecast bias which is the natural tendency to be overtly optimistic or pessimistic without any substantive evidence to support one or the other case. Sometimes how the information is presented: visually or in tabular format – can lead to sins of the error of omission and commission leading the organization and judgement down paths that are unwarranted and just plain wrong. Thus, it is important to be aware of how statistical biases come into play to sabotage your decision framework.

One of the finest illustrations of misjudgment has been laid out by Charlie Munger. Here is the excerpt link : https://fs.blog/great-talks/psychology-human-misjudgment/ He lays out a very comprehensive 25 Biases that ail decision making. Once again, stripping biases do not necessarily result in accuracy — it increases the variability of outcomes that might be clustered around a mean that might be closer to accuracy than otherwise.

Variability is Noise. We do not know a priori what the expected mean is. We are close, but not quite. There is noise or a whole set of outcomes around the mean. Viewing things closer to the ground versus higher would still create a likelihood of accepting a false hypothesis or rejecting a true one. Noise is extremely hard to sift through, but how you can sift through the noise to arrive at those signals that are determining factors, is critical to organization success. To get to this territory, we have eliminated the cognitive and statistical biases. Now is the search for the signal. What do we do then? An increase in noise impairs accuracy. To improve accuracy, you either reduce noise or figure out those indicators that signal an accurate measure.

This is where algorithmic thinking comes into play. You start establishing well tested algorithms in specific use cases and cross-validate that across a large set of experiments or scenarios. It has been proved that algorithmic tools are, in the aggregate, superior to human judgement – since it systematically can surface causal and correlative relationships. Furthermore, special tools like principal component analysis and factory analysis can incorporate a large input variable set and establish the patterns that would be impregnable for even System 2 mindset to comprehend. This will bring decision making toward the signal variants and thus fortify decision making.

The final element is to assess the time commitment required to go through all the stages. Given infinite time and resources, there is always a high likelihood of arriving at those signals that are material for sound decision making. Alas, the reality of life does not play well to that assumption! Time and resources are constraints … so one must make do with sub-optimal decision making and establish a cutoff point wherein the benefits outweigh the risks of looking for another alternative. That comes down to the realm of judgements. While George Stigler, a Nobel Laureate in Economics, introduce search optimization in fixed sequential search – a more concrete example has been illustrated in “Algorithms to Live By” by Christian & Griffiths. They suggested an holy grail response: 37% is the accurate answer. In other words, you would reach a suboptimal decision by ensuring that you have explored up to 37% of your estimated maximum effort. While the estimated maximum effort is quite ambiguous and afflicted with all of the elements of bias (cognitive and statistical), the best thinking is to be as honest as possible to assess that effort and then draw your search threshold cutoff.

An important element of leadership is about making calls. Good calls, not necessarily the best calls! Calls weighing all possible circumstances that one can, being aware of the biases, bringing in a diverse set of knowledge and opinions, falling back upon agnostic tools in statistics, and knowing when it is appropriate to have learnt enough to pull the trigger. And it is important to cascade the principles of decision making and the underlying complexity into and across the organization.

Navigating Chaos and Model Thinking

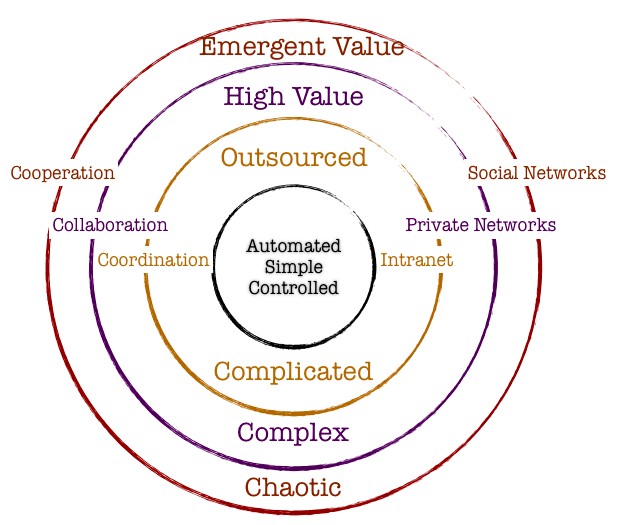

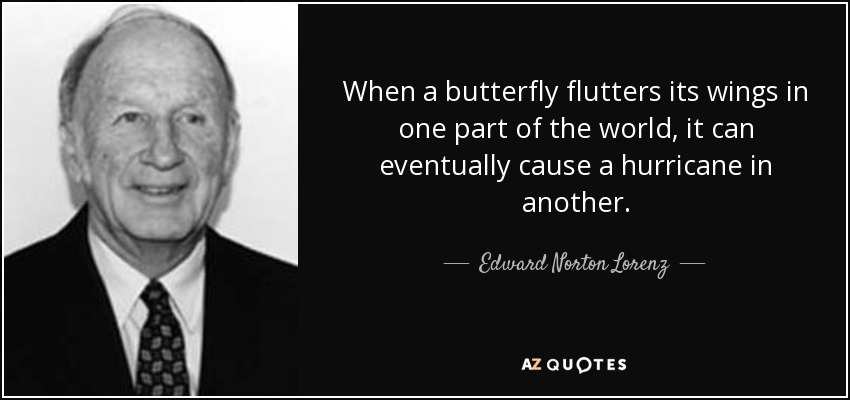

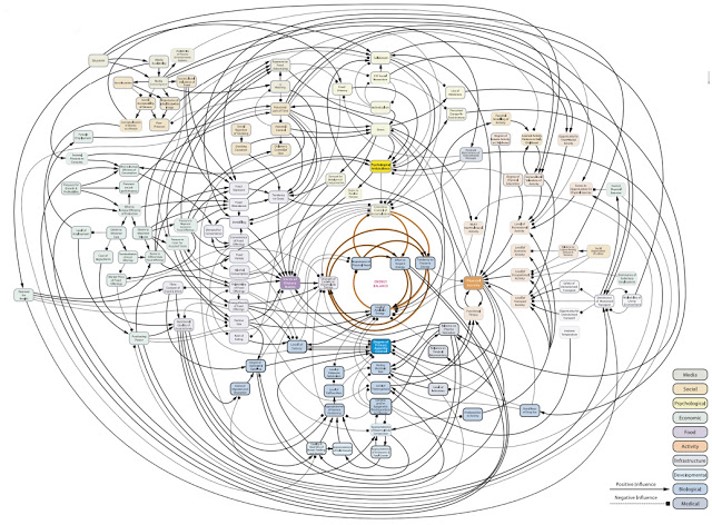

An inherent property of a chaotic system is that slight changes in initial conditions in the system result in a disproportionate change in outcome that is difficult to predict. Chaotic systems appear to create outcomes that appear to be random: they are generated by simple and non-random processes but the complexity of such systems emerge over time driven by numerous iterations of simple rules. The elements that compose chaotic systems might be few in number, but these elements work together to produce an intricate set of dynamics that amplifies the outcome and makes it hard to be predictable. These systems evolve over time, doing so according to rules and initial conditions and how the constituent elements work together.

Complex systems are characterized by emergence. The interactions between the elements of the system with its environment create new properties which influence the structural development of the system and the roles of the agents. In such systems there is self-organization characteristics that occur, and hence it is difficult to study and effect a system by studying the constituent parts that comprise it. The task becomes even more formidable when one faces the prevalent reality that most systems exhibit non-linear dynamics.

So how do we incorporate management practices in the face of chaos and complexity that is inherent in organization structure and market dynamics? It would be interesting to study this in light of the evolution of management principles in keeping with the evolution of scientific paradigms.

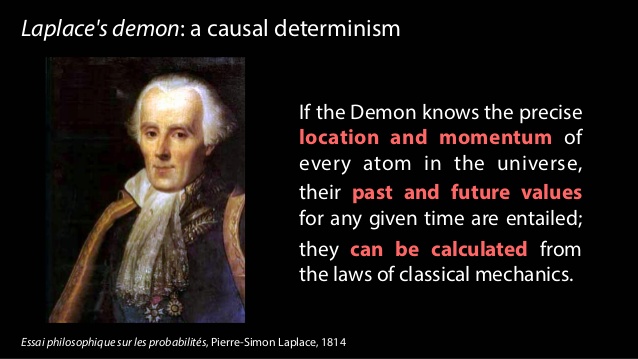

Newtonian Mechanics and Taylorism

Traditional organization management has been heavily influenced by Newtonian mechanics. The five key assumptions of Newtonian mechanics are:

- Reality is objective

- Systems are linear and there is a presumption that all underlying cause and effect are linear

- Knowledge is empirical and acquired through collecting and analyzing data with the focus on surfacing regularities, predictability and control

- Systems are inherently efficient. Systems almost always follows the path of least resistance

- If inputs and process is managed, the outcomes are predictable

Frederick Taylor is the father of operational research and his methods were deployed in automotive companies in the 1940’s. Workers and processes are input elements to ensure that the machine functions per expectations. There was a linearity employed in principle. Management role was that of observation and control and the system would best function under hierarchical operating principles. Mass and efficient production were the hallmarks of management goal.

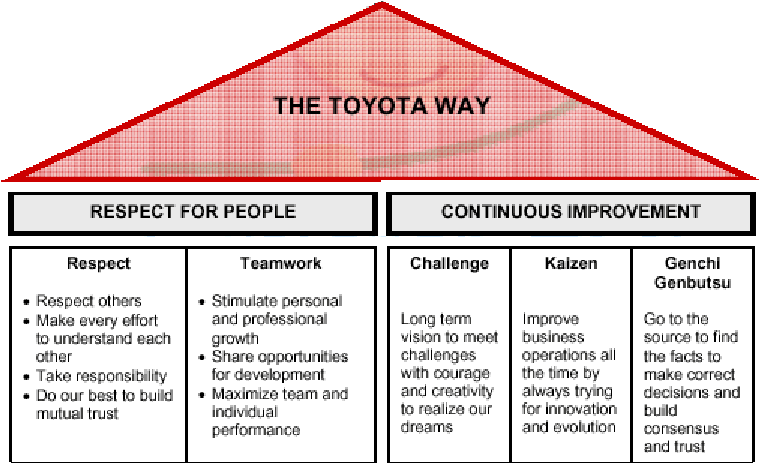

Randomness and the Toyota Way

The randomness paradigm recognized uncertainty as a pervasive constant. The various methods that Toyota Way invoked around 5W rested on the assumption that understanding the cause and effect is instrumental and this inclined management toward a more process-based deployment. Learning is introduced in this model as a dynamic variable and there is a lot of emphasis on the agents and providing them the clarity and purpose of their tasks. Efficiencies and quality are presumably driven by the rank and file and autonomous decisions are allowed. The management principle moves away from hierarchical and top-down to a more responsibility driven labor force.

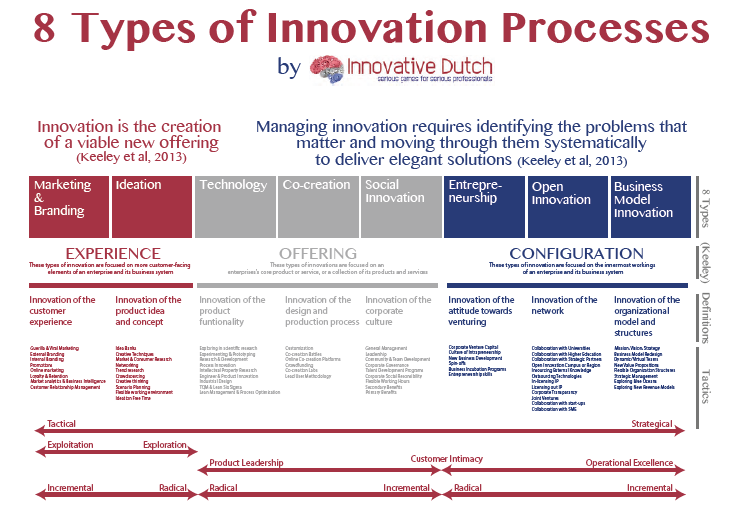

Complexity and Chaos and the Nimble Organization

Increasing complexity has led to more demands on the organization. With the advent of social media and rapid information distribution and a general rise in consciousness around social impact, organizations have to balance out multiple objectives. Any small change in initial condition can lead to major outcomes: an advertising mistake can become a global PR nightmare; a word taken out of context could have huge ramifications that might immediately reflect on the stock price; an employee complaint could force management change. Increasing data and knowledge are not sufficient to ensure long-term success. In fact, there is no clear recipe to guarantee success in an age fraught with non-linearity, emergence and disequilibrium. To succeed in this environment entails the development of a learning organization that is not governed by fixed top-down rules: rather the rules are simple and the guidance is around the purpose of the system or the organization. It is best left to intellectual capital to self-organize rapidly in response to external information to adapt and make changes to ensure organization resilience and success.

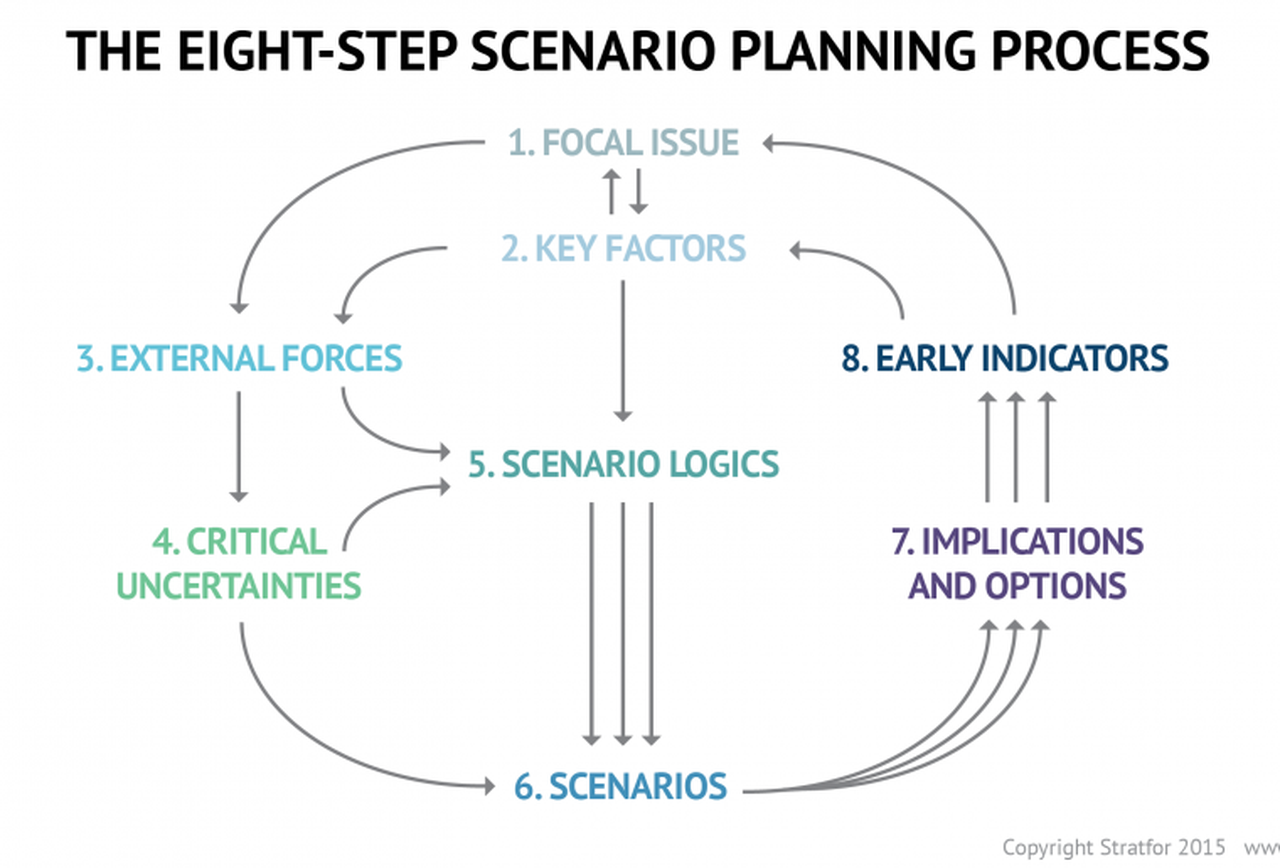

Companies are dynamic non-linear adaptive systems. The elements in the system are constantly interacting between themselves and their external environment. This creates new emergent properties that are sensitive to the initial conditions. A change in purpose or strategic positioning could set a domino effect and can lead to outcomes that are not predictable. Decisions are pushed out to all levels in the organization, since the presumption is that local and diverse knowledge that spontaneously emerge in response to stimuli is a superior structure than managing for complexity in a centralized manner. Thus, methods that can generate ideas, create innovation habitats, and embrace failures as providing new opportunities to learn are best practices that companies must follow. Traditional long-term planning and forecasting is becoming a far harder exercise and practically impossible. Thus, planning is more around strategic mindset, scenario planning, allowing local rules to auto generate without direct supervision, encourage dissent and diversity, stimulate creativity and establishing clarity of purpose and broad guidelines are the hall marks of success.

Principles of Leadership in a New Age

We have already explored the fact that traditional leadership models originated in the context of mass production and efficiencies. These models are arcane in our information era today, where systems are characterized by exponential dynamism of variables, increased density of interactions, increased globalization and interconnectedness, massive information distribution at increasing rapidity, and a general toward economies driven by free will of the participants rather than a central authority.

Complexity Leadership Theory (Uhl-Bien) is a “framework for leadership that enables the learning, creative and adaptive capacity of complex adaptive systems in knowledge-producing organizations or organizational units. Since planning for the long-term is virtually impossible, Leadership has to be armed with different tool sets to steer the organization toward achieving its purpose. Leaders take on enabler role rather than controller role: empowerment supplants control. Leadership is not about focus on traits of a single leader: rather, it redirects emphasis from individual leaders to leadership as an organizational phenomenon. Leadership is a trait rather than an individual. We recognize that complex systems have lot of interacting agents – in business parlance, which might constitute labor and capital. Introducing complexity leadership is to empower all of the agents with the ability to lead their sub-units toward a common shared purpose. Different agents can become leaders in different roles as their tasks or roles morph rapidly: it is not necessarily defined by a formal appointment or knighthood in title.

Thus, complexity of our modern-day reality demands a new strategic toolset for the new leader. The most important skills would be complex seeing, complex thinking, complex knowing, complex acting, complex trusting and complex being. (Elena Osmodo, 2012)

Complex Seeing: Reality is inherently subjective. It is a page of the Heisenberg Uncertainty principle that posits that the independence between the observer and the observed is not real. If leaders are not aware of this independence, they run the risk of engaging in decisions that are fraught with bias. They will continue to perceive reality with the same lens that they have perceived reality in the past, despite the fact that undercurrents and riptides of increasingly exponential systems are tearing away their “perceived reality.” Leader have to be conscious about the tectonic shifts, reevaluate their own intentions, probe and exclude biases that could cloud the fidelity of their decisions, and engage in a continuous learning process. The ability to sift and see through this complexity sets the initial condition upon which the entire system’s efficacy and trajectory rests.

Complex Thinking: Leaders have to be cognizant of falling prey to linear simple cause and effect thinking. On the contrary, leaders have to engage in counter-intuitive thinking, brainstorming and creative thinking. In addition, encouraging dissent, debates and diversity encourage new strains of thought and ideas.

Complex Feeling: Leaders must maintain high levels of energy and be optimistic of the future. Failures are not scoffed at; rather they are simply another window for learning. Leaders have to promote positive and productive emotional interactions. The leaders are tasked to increase positive feedback loops while reducing negative feedback mechanisms to the extent possible. Entropy and attrition taxes any system as is: the leader’s job is to set up safe environment to inculcate respect through general guidelines and leading by example.

Complex Knowing: Leadership is tasked with formulating simple rules to enable learned and quicker decision making across the organization. Leaders must provide a common purpose, interconnect people with symbols and metaphors, and continually reiterate the raison d’etre of the organization. Knowing is articulating: leadership has to articulate and be humble to any new and novel challenges and counterfactuals that might arise. The leader has to establish systems of knowledge: collective learning, collaborative learning and organizational learning. Collective learning is the ability of the collective to learn from experiences drawn from the vast set of individual actors operating in the system. Collaborative learning results due to interaction of agents and clusters in the organization. Learning organization, as Senge defines it, is “where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspirations are set free, and where people are continually learning to see the whole together.”

Complex Acting: Complex action is the ability of the leader to not only work toward benefiting the agents in his/her purview, but also to ensure that the benefits resonates to a whole which by definition is greater than the sum of the parts. Complex acting is to take specific action-oriented steps that largely reflect the values that the organization represents in its environmental context.

Complex Trusting: Decentralization requires conferring power to local agents. For decentralization to work effectively, leaders have to trust that the agents will, in the aggregate, work toward advancing the organization. The cost of managing top-down is far more than the benefits that a trust-based decentralized system would work in a dynamic environment resplendent with the novelty of chaos and complexity.

Complex Being: This is the ability of the leaser to favor and encourage communication across the organization rapidly. The leader needs to encourage relationships and inter-functional dialogue.

The role of complex leaders is to design adaptive systems that are able to cope with challenging and novel environments by establishing a few rules and encouraging agents to self-organize autonomously at local levels to solve challenges. The leader’s main role in this exercise is to set the strategic directions and the guidelines and let the organizations run.

Chaos and the tide of Entropy!

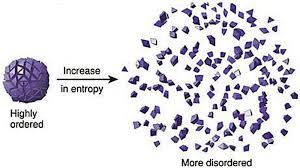

We have discussed chaos. It is rooted in the fundamental idea that small changes in the initial condition in a system can amplify the impact on the final outcome in the system. Let us now look at another sibling in systems literature – namely, the concept of entropy. We will then attempt to bridge these two concepts since they are inherent in all systems.

Entropy arises from the law of thermodynamics. Let us state all three laws:

- First law is known as the Lay of Conservation of Energy which states that energy can neither be created nor destroyed: energy can only be transferred from one form to another. Thus, if there is work in terms of energy transformation in a system, there is equivalent loss of energy transformation around the system. This fact balances the first law of thermodynamics.

- Second law of thermodynamics states that the entropy of any isolated system always increases. Entropy always increases, and rarely ever decreases. If a locker room is not tidied, entropy dictates that it will become messier and more disorderly over time. In other words, all systems that are stagnant will inviolably run against entropy which would lead to its undoing over time. Over time the state of disorganization increases. While energy cannot be created or destroyed, as per the First Law, it certainly can change from useful energy to less useful energy.

- Third law establishes that the entropy of a system approaches a constant value as the temperature approaches absolute zero. Thus, the entropy of a pure crystalline substance at absolute zero temperature is zero. However, if there is any imperfection that resides in the crystalline structure, there will be some entropy that will act upon it.

Entropy refers to a measure of disorganization. Thus people in a crowd that is widely spread out across a large stadium has high entropy whereas it would constitute low entropy if people are all huddled in one corner of the stadium. Entropy is the quantitative measure of the process – namely, how much energy has been spent from being localized to being diffused in a system. Entropy is enabled by motion or interaction of elements in a system, but is actualized by the process of interaction. All particles work toward spontaneously dissipating their energy if they are not curtailed from doing so. In other words, there is an inherent will, philosophically speaking, of a system to dissipate energy and that process of dissipation is entropy. However, it makes no effort to figure out how quickly entropy kicks into gear – it is this fact that makes it difficult to predict the overall state of the system.

Chaos, as we have already discussed, makes systems unpredictable because of perturbations in the initial state. Entropy is the dissipation of energy in the system, but there is no standard way of knowing the parameter of how quickly entropy would set in. There are thus two very interesting elements in systems that almost work simultaneously to ensure that predictability of systems become harder.

Another way of looking at entropy is to view this as a tax that the system charges us when it goes to work on our behalf. If we are purposefully calibrating a system to meet a certain purpose, there is inevitably a corresponding usage of energy or dissipation of energy otherwise known as entropy that is working in parallel. A common example that we are familiar with is mass industrialization initiatives. Mass industrialization has impacts on environment, disease, resource depletion, and a general decay of life in some form. If entropy as we understand it is an irreversible phenomenon, then there is virtually nothing that can be done to eliminate it. It is a permanent tax of varying magnitude in the system.

Humans have since early times have tried to formulate a working framework of the world around them. To do that, they have crafted various models and drawn upon different analogies to lend credence to one way of thinking over another. Either way, they have been left best to wrestle with approximations: approximations associated with their understanding of the initial conditions, approximations on model mechanics, approximations on the tax that the system inevitably charges, and the approximate distribution of potential outcomes. Despite valiant efforts to reduce the framework to physical versus behavioral phenomena, their final task of creating or developing a predictable system has not worked. While physical laws of nature describe physical phenomena, the behavioral laws describe non-deterministic phenomena. If linear equations are used as tools to understand the physical laws following the principles of classical Newtonian mechanics, the non-linear observations marred any consistent and comprehensive framework for clear understanding. Entropy reaches out toward an irreversible thermal death: there is an inherent fatalism associated with the Second Law of Thermodynamics. However, if that is presumed to be the case, how is it that human evolution has jumped across multiple chasms and have evolved to what it is today? If indeed entropy is the tax, one could argue that chaos with its bounded but amplified mechanics have allowed the human race to continue.

Let us now deliberate on this observation of Richard Feynmann, a Nobel Laurate in physics – “So we now have to talk about what we mean by disorder and what we mean by order. … Suppose we divide the space into little volume elements. If we have black and white molecules, how many ways could we distribute them among the volume elements so that white is on one side and black is on the other? On the other hand, how many ways could we distribute them with no restriction on which goes where? Clearly, there are many more ways to arrange them in the latter case.

We measure “disorder” by the number of ways that the insides can be arranged, so that from the outside it looks the same. The logarithm of that number of ways is the entropy. The number of ways in the separated case is less, so the entropy is less, or the “disorder” is less.” It is commonly also alluded to as the distinction between microstates and macrostates. Essentially, it says that there could be innumerable microstates although from an outsider looking in – there is only one microstate. The number of microstates hints at the system having more entropy.

In a different way, we ran across this wonderful example: A professor distributes chocolates to students in the class. He has 35 students but he distributes 25 chocolates. He throws those chocolates to the students and some students might have more than others. The students do not know that the professor had only 25 chocolates: they have presumed that there were 35 chocolates. So the end result is that the students are disconcerted because they perceive that the other students have more chocolates than they have distributed but the system as a whole shows that there are only 25 chocolates. Regardless of all of the ways that the 25 chocolates are configured among the students, the microstate is stable.

So what is Feynmann and the chocolate example suggesting for our purpose of understanding the impact of entropy on systems: Our understanding is that the reconfiguration or the potential permutations of elements in the system that reflect the various microstates hint at higher entropy but in reality has no impact on the microstate per se except that the microstate has inherently higher entropy. Does this mean that the macrostate thus has a shorter life-span? Does this mean that the microstate is inherently more unstable? Could this mean an exponential decay factor in that state? The answer to all of the above questions is not always. Entropy is a physical phenomenon but to abstract this out to enable a study of organic systems that represent super complex macrostates and arrive at some predictable pattern of decay is a bridge too far! If we were to strictly follow the precepts of the Second Law and just for a moment forget about Chaos, one could surmise that evolution is not a measure of progress, it is simply a reconfiguration.

Theodosius Dobzhansky, a well known physicist, says: “Seen in retrospect, evolution as a whole doubtless had a general direction, from simple to complex, from dependence on to relative independence of the environment, to greater and greater autonomy of individuals, greater and greater development of sense organs and nervous systems conveying and processing information about the state of the organism’s surroundings, and finally greater and greater consciousness. You can call this direction progress or by some other name.”

Harold Mosowitz says “Life is organization. From prokaryotic cells, eukaryotic cells, tissues and organs, to plants and animals, families, communities, ecosystems, and living planets, life is organization, at every scale. The evolution of life is the increase of biological organization, if it is anything. Clearly, if life originates and makes evolutionary progress without organizing input somehow supplied, then something has organized itself. Logical entropy in a closed system has decreased. This is the violation that people are getting at, when they say that life violates the second law of thermodynamics. This violation, the decrease of logical entropy in a closed system, must happen continually in the Darwinian account of evolutionary progress.”

Entropy occurs in all systems. That is an indisputable fact. However, if we start defining boundaries, then we are prone to see that these bounded systems decay faster. However, if we open up the system to leave it unbounded, then there are a lot of other forces that come into play that is tantamount to some net progress. While it might be true that energy balances out, what we miss as social scientists or model builders or avid students of systems – we miss out on indices that reflect on leaps in quality and resilience and a horde of other factors that stabilizes the system despite the constant and ominous presence of entropy’s inner workings.