Category Archives: Analytics

The Finance Playbook for Scaling Complexity Without Chaos

From Controlled Growth to Operational Grace

Somewhere between Series A optimism and Series D pressure sits the very real challenge of scale. Not just growth for its own sake but growth with control, precision, and purpose. A well-run finance function becomes less about keeping the lights on and more about lighting the runway. I have seen it repeatedly. You can double ARR, but if your deal desk, revenue operations, or quote-to-cash processes are even slightly out of step, you are scaling chaos, not a company.

Finance does not scale with spreadsheets and heroics. It scales with clarity. With every dollar, every headcount, and every workflow needing to be justified in terms of scale, simplicity must be the goal. I recall sitting in a boardroom where the CEO proudly announced a doubling of the top line. But it came at the cost of three overlapping CPQ systems, elongated sales cycles, rogue discounting, and a pipeline no one trusted. We did not have a scale problem. We had a complexity problem disguised as growth.

OKRs Are Not Just for Product Teams

When finance is integrated into company OKRs, magic happens. We begin aligning incentives across sales, legal, product, and customer success teams. Suddenly, the sales operations team is not just counting bookings but shaping them. Deal desk isn’t just a speed bump before legal review, but a value architect. Our quote-to-cash process is no longer a ticketing system but a flywheel for margin expansion.

At a Series B company, their shift began by tying financial metrics directly to the revenue team’s OKRs. Quota retirement was not enough. They measured the booked gross margin. Customer acquisition cost. Implementation of velocity. The sales team was initially skeptical but soon began asking more insightful questions. Deals that initially appeared promising were flagged early. Others that seemed too complicated were simplified before they even reached RevOps. Revenue is often seen as art. But finance gives it rhythm.

Scaling Complexity Despite the Chaos

The truth is that chaos is not the enemy of scale. Chaos is the cost of momentum. Every startup that is truly growing at a pace inevitably creates complexity. Systems become tangled. Roles blur. Approvals drift. That is not failure. That is physics. What separates successful companies is not the absence of chaos but their ability to organize it.

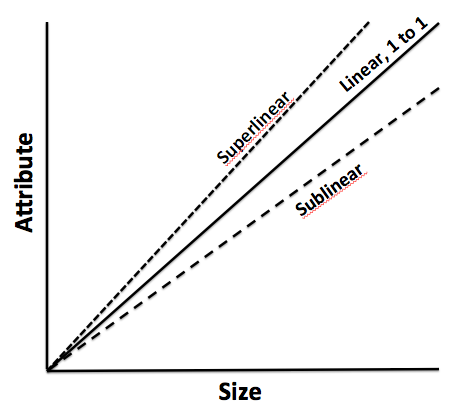

I often compare this to managing a growing city. You do not stop new buildings from going up just because traffic worsens. You introduce traffic lights, zoning laws, and transit systems that support the growth. In finance, that means being ready to evolve processes as soon as growth introduces friction. It means designing modular systems where complexity is absorbed rather than resisted. You do not simplify the growth. You streamline the experience of growing. Read Scale by Geoffrey West. Much of my interest in complexity theory and architecture for scale comes from it. Also, look out for my book, which will be published in February 2026: Complexity and Scale: Managing Order from Chaos. This book aligns literature in complexity theory with the microeconomics of scaling vectors and enterprise architecture.

At a late-stage Series C company, the sales motion had shifted from land-and-expand to enterprise deals with multi-year terms and custom payment structures. The CPQ tool was unable to keep up. Rather than immediately overhauling the tool, they developed middleware logic that routed high-complexity deals through a streamlined approval process, while allowing low-risk deals to proceed unimpeded. The system scaled without slowing. Complexity still existed, but it no longer dictated pace.

Cash Discipline: The Ultimate Growth KPI

Cash is not just oxygen. It is alignment. When finance speaks early and often about burn efficiency, marginal unit economics, and working capital velocity, we move from gatekeepers to enablers. I often remind founders that the cost of sales is not just the commission plan. It’s in the way deals are structured. It’s in how fast a contract can be approved. It’s in how many hands a quote needs to pass through.

At one Series A professional services firm, they introduced a “Deal ROI Calculator” at the deal desk. It calculated not just price and term but implementation effort, support burden, and payback period. The result was staggering. Win rates remained stable, but average deal profitability increased by 17 percent. Sales teams began choosing deals differently. Finance was not saying no. It was saying, “Say yes, but smarter.”

Velocity is a Decision, Not a Circumstance

The best-run companies are not faster because they have fewer meetings. They are faster because decisions are closer to the data. Finance’s job is to put insight into the hands of those making the call. The goal is not to make perfect decisions. It is to make the best decision possible with the available data and revisit it quickly.

In one post-Series A firm, we embedded finance analysts inside revenue operations. It blurred the traditional lines but sped up decision-making. Discount approvals have been reduced from 48 hours to 12-24 hours. Pricing strategies became iterative. A finance analyst co-piloted the forecast and flagged gaps weeks earlier than our CRM did. It wasn’t about more control. It was about more confidence.

When Process Feels Like Progress

It is tempting to think that structure slows things down. However, the right QTC design can unlock margin, trust, and speed simultaneously. Imagine a deal desk that empowers sales to configure deals within prudent guardrails. Or a contract management workflow that automatically flags legal risks. These are not dreams. These are the functions we have implemented.

The companies that scale well are not perfect. But their finance teams understand that complexity compounds quietly. And so, we design our systems not to prevent chaos but to make good decisions routine. We don’t wait for the fire drill. We design out the fire.

Make Your Revenue Operations Your Secret Weapon

If your finance team still views sales operations as a reporting function, you are underutilizing a strategic lever. Revenue operations, when empowered, can close the gap between bookings and billings. They can forecast with precision. They can flag incentive misalignment. One of the best RevOps leaders I worked with used to say, “I don’t run reports. I run clarity.” That clarity was worth more than any point solution we bought.

In scaling environments, automation is not optional. But automation alone does not save a broken process. Finance must own the blueprint. Every system, from CRM to CPQ to ERP, must speak the same language. Data fragmentation is not just annoying. It is value-destructive.

What Should You Do Now?

Ask yourself: Does finance have visibility into every step of the revenue funnel? Do our QTC processes support strategic flexibility? Is our deal desk a source of friction or a source of enablement? Can our sales comp plan be audited and justified in a board meeting without flinching?

These are not theoretical. They are the difference between Series C confusion and Series D confidence.

Let’s Make This Personal

I have seen incredible operators get buried under process debt because they mistook motion for progress. I have seen lean finance teams punch above their weight because they anchored their operating model in OKRs, cash efficiency, and rapid decision cycles. I have also seen the opposite. A sales ops function sitting in the corner. A deal desk no one trusts. A QTC process where no one knows who owns what.

These are fixable. But only if finance decides to lead. Not just report.

So here is my invitation. If you are a CFO, a CRO, a GC, or a CEO reading this, take one day this quarter to walk your revenue path from lead to cash. Sit with the people who feel the friction. Map the handoffs. And then ask, is this how we scale with control? Do you have the right processes in place? Do you have the technology to activate the process and minimize the friction?

AI and the Evolving Role of CFOs

For much of the twentieth century, the role of the Chief Financial Officer was understood in familiar terms. A steward of control. A master of precision. A guardian of the balance sheet. The CFO was expected to be meticulous, cautious, and above all, accountable. Decisions were made through careful deliberation. Assumptions were scrutinized. Numbers did not lie; they merely required interpretation. There was an art to the conservatism and a quiet pride in it. Order, after all, was the currency of good finance.

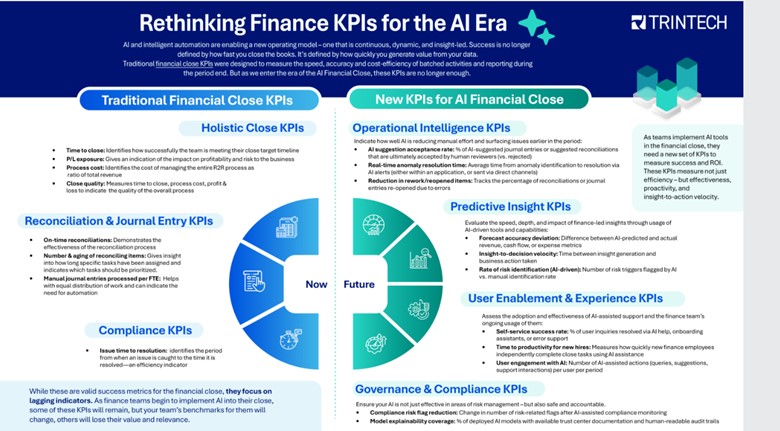

Then artificial intelligence arrived—not like a polite guest knocking at the door, but more like a storm bursting through the windows, unsettling assumptions, and rewriting the rules of what it means to manage the financial function. Suddenly, the world of structured inputs and predictable outputs became a dynamic theater of probabilities, models, and machine learning loops. The close of the quarter, once a ritual of discipline and human labor, was now something that could be shortened by algorithms. Forecasts, previously the result of sleepless nights and spreadsheets, could now be generated in minutes. And yet, beneath the glow of progress, a quieter question lingered in the minds of financial leaders: Are we still in control?

The paradox is sharp. AI promises greater accuracy, faster insights, and efficiencies that were once unimaginable. But it also introduces new vulnerabilities. Decisions made by machines cannot always be explained by humans. Data patterns shift, and models evolve in ways that are hard to monitor, let alone govern. The very automation that liberates teams from tedious work may also obscure how decisions are being made. For CFOs, whose role rests on the fulcrum of control and transparency, this presents a challenge unlike any other.

To understand what is at stake, one must first appreciate the philosophical shift taking place. Traditional finance systems were built around rules. If a transaction did not match a predefined criterion, it was flagged. If a value exceeded a threshold, it triggered an alert. There was a hierarchy to control. Approvals, audits, reconciliations—all followed a chain of accountability. AI, however, does not follow rules in the conventional sense. It learns patterns. It makes predictions. It adjusts based on what it sees. In place of linear logic, it offers probability. In place of rules, it gives suggestions.

This does not make AI untrustworthy, but it does make it unfamiliar. And unfamiliarity breeds caution. For CFOs who have spent decades refining control environments, AI is not merely a tool. It is a new philosophy of decision-making. And it is one that challenges the muscle memory of the profession.

What, then, does it mean to stay in control in an AI-enhanced finance function? It begins with visibility. CFOs must ensure that the models driving key decisions—forecasts, risk assessments, working capital allocations—are not black boxes. Every algorithm must come with a passport. What data went into it? What assumptions were made? How does it behave when conditions change? These are not technical questions alone. They are governance questions. And they sit at the heart of responsible financial leadership.

Equally critical is the quality of data. An AI model is only as reliable as the information it consumes. Dirty data, incomplete records, or inconsistent definitions can quickly derail the most sophisticated tools. In this environment, the finance function must evolve from being a consumer of data to a custodian of it. The general ledger, once a passive repository of transactions, becomes part of a living data ecosystem. Consistency matters. Lineage matters. And above all, context matters. A forecast that looks brilliant in isolation may collapse under scrutiny if it was trained on flawed assumptions.

But visibility and data are only the beginning. As AI takes on more tasks that were once performed by humans, the traditional architecture of control must be reimagined. Consider the principle of segregation of duties. In the old world, one person entered the invoice, another approved it, and a third reviewed the ledger. These checks and balances were designed to prevent fraud, errors, and concentration of power. But what happens when an AI model is performing all three functions? Who oversees the algorithm? Who reviews the reviewer?

The answer is not to retreat from automation, but to introduce new forms of oversight. CFOs must create protocols for algorithmic accountability. This means establishing thresholds for machine-generated recommendations, building escalation paths for exceptions, and defining moments when human judgement must intervene. It is not about mistrusting the machine. It is about ensuring that the machine is governed with the same discipline once reserved for people.

And then there is the question of resilience. AI introduces new dependencies—on data pipelines, on cloud infrastructures, on model stability. A glitch in a forecasting model could ripple through the entire enterprise plan. A misfire in an expense classifier could disrupt a close. These are not hypothetical risks. They are operational realities. Just as organizations have disaster recovery plans for cyber breaches or system outages, they must now develop contingency plans for AI failures. The models must be monitored. The outputs must be tested. And the humans must be prepared to take over when the automation stumbles.

Beneath all of this, however, lies a deeper cultural transformation. The finance team of the future will not be composed solely of accountants, auditors, and analysts. It will also include data scientists, machine learning specialists, and process architects. The rhythm of work will shift—from data entry and manual reconciliations to interpretation, supervision, and strategic advising. This demands a new kind of fluency. Not necessarily the ability to write code, but the ability to understand how AI works, what it can do, and where its boundaries lie.

This is not a small ask. It requires training, cross-functional collaboration, and a willingness to challenge tradition. But it also opens the door to a more intellectually rich finance function—one where humans and machines collaborate to generate insights that neither could have achieved alone.

If there is a guiding principle in all of this, it is that control does not mean resisting change. It means shaping it. For CFOs, the task is not to retreat into spreadsheets or resist the encroachment of algorithms. It is to lead the integration of intelligence into every corner of the finance operation. To set the standards, define the guardrails, and ensure that the organization embraces automation not as a surrender of responsibility, but as an evolution of it.

Because in the end, the goal is not simply to automate. It is to augment. Not to replace judgement, but to elevate it. Not to remove the human hand from finance, but to position it where it matters most: at the helm, guiding the ship through faster currents, with clearer vision and steadier hands.

Artificial intelligence may never match the emotional weight of human intuition. It may not understand the stakes behind a quarter’s earnings or the subtle implications of a line item in a note to shareholders. But it can free up time. It can provide clarity. It can make the financial function faster, more adaptive, and more resilient.

And if the CFO of the past was a gatekeeper, the CFO of the future will be a choreographer—balancing risk and intelligence, control and creativity, all while ensuring that the numbers, no matter how complex their origin, still tell a story that is grounded in truth.

The machines are here. They are learning. And they are listening. The challenge is not to contain them, but to guide them—thoughtfully, carefully, and with the discipline that has always defined great finance.

Because in this new world, control is not lost. It is simply redefined.

The Power of Customer Lifetime Value in Modern Business

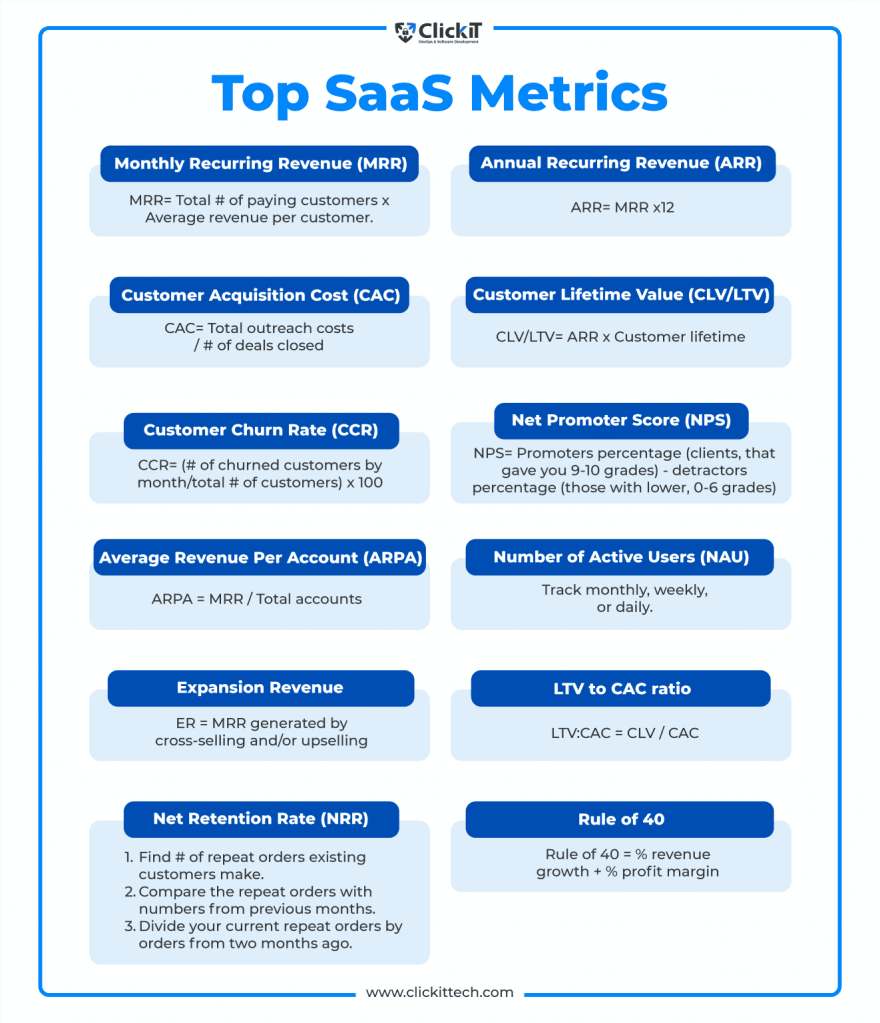

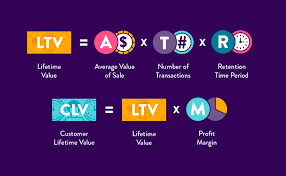

In contemporary business discourse, few metrics carry the strategic weight of Customer Lifetime Value (CLV). CLV and CAC are prime metrics. For modern enterprises navigating an era defined by digital acceleration, subscription economies, and relentless competition, CLV represents a unifying force, uniting finance, marketing, and strategy into a single metric that measures not only transactions but also the value of relationships. Far more than a spreadsheet calculation, CLV crystallizes lifetime revenue, loyalty, referral impact, and long-term financial performance into a quantifiable asset.

This article explores CLV’s origins, its mathematical foundations, its role as a strategic North Star across organizational functions, and the practical systems required to integrate it fully into corporate culture and capital allocation. It also highlights potential pitfalls and ethical implications.

I. CLV as a Cross-Functional Metric

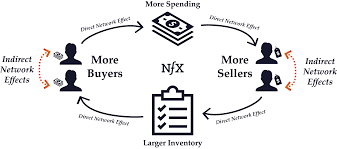

CLV evolved from a simple acknowledgement: not all customers are equally valuable, and many businesses would prosper more by nurturing relationships than chasing clicks. The transition from single-sale tallies to lifetime relationship value gained momentum with the rise of subscription models—telecom plans, SaaS platforms, and membership programs—where the fiscal significance of recurring revenue became unmistakable.

This shift reframed capital deployment and decision-making:

- Marketing no longer seeks volume unquestioningly but targets segments with high long-term value.

- Finance integrates CLV into valuation models and capital allocation frameworks.

- Strategy uses it to guide M&A decisions, pricing stratagems, and product roadmap prioritization.

Because CLV is simultaneously a financial measurement and a customer-centric tool, it builds bridges—translating marketing activation into board-level impact.

II. How to calculate CLV

At its core, CLV employs economic modeling similar to net present value. A basic formula:

CLV = ∑ (t=0 to T) [(Rt – Ct) / (1 + d)^t]

- Rt = revenue generated at time t

- Ct = cost to serve/acquire at time t

- d = discount rate

- T = time horizon

This anchors CLV in well-accepted financial principles: discounted future cash flows, cost allocation, and multi-period forecasting. It satisfies CFO requirements for rigor and measurability.

However, marketing leaders often expand this to capture:

- Referral value (Rt includes not just direct sales, but influenced purchases)

- Emotional or brand-lift dimensions (e.g., window customers who convert later)

- Upselling, cross-selling, and tiered monetization over time

These expansions refine CLV into a dynamic forecast rather than a static average—one that responds to segmentation and behavioral triggers.

III. CLV as a Board-Level Metric

A. Investment and Capital Prioritization

Traditional capital decisions rely on ROI, return on invested capital (ROIC), and earnings multiples. CLV adds nuance: it gauges not only immediate returns but extended client relationships. This enables an expanded view of capital returns.

For example, a company might shift budget from low-CLV acquisition channels to retention-focused strategies—investing more in on-boarding, product experience, or customer success. These initiatives, once considered costs, now become yield-generating assets.

B. Segment-Based Acquisition

CLV enables precision targeting. A segment that delivers a 6:1 lifetime value-to-acquisition-cost (LTV:CAC) ratio is clearly more valuable than one delivering 2:1. Marketing reallocates spend accordingly, optimizing strategic segmentation and media mix, tuning messaging for high-value cohorts.

Because CLV is quantifiable and forward-looking, it naturally aligns marketing decisions with shareholder-driven metrics.

C. Tiered Pricing and Customer Monetization

CLV is also central to monetization strategy. Churn, upgrade rates, renewal behaviors, and pricing power all can be evaluated through the lens of customer value over time. Versioning, premium tiers, loyalty benefits—all become levers to maximize lifetime value. Finance and strategy teams model these scenarios to identify combinations that yield optimal returns.

D. Strategic Partnerships and M&A

CLV informs deeper decisions about partnerships and mergers. In evaluating a potential platform acquisition, projected contribution to overall CLV may be a decisive factor, especially when combined customer pools or cross-sell ecosystems can amplify lifetime revenue. It embeds customer value insights into due diligence and valuation calculations.

IV. Organizational Integration: A Strategic Imperative

Effective CLV deployment requires more than good analytics—it demands structural clarity and cultural alignment across three key functions.

A. Finance as Architect

Finance teams frame the assumptions—discount rates, cost allocation, margin calibration—and embed CLV into broader financial planning and analysis. Their task: convert behavioral data and modeling into company-wide decision frameworks used in investment reviews, budgeting, and forecasting processes.

B. Marketing as Activation Engine

Marketing owns customer acquisition, retention campaigns, referral programs, and product messaging. Their role is to feed the CLV model with real data: conversion rates, churn, promotion impact, and engagement flows. In doing so, campaigns become precision tools tuned to maximize customer yield rather than volume alone.

C. Strategy as Systems Designer

The strategy team weaves CLV outputs into product roadmaps, pricing strategy, partnership design, and geographic expansion. Using CLV foliated by cohort and channel, strategy leaders can sequence investments to align with long-term margin objectives—such as a five-year CLV-driven revenue mix.

V. Embedding CLV Into Corporate Processes

The following five practices have proven effective at embedding CLV into organizational DNA:

- Executive Dashboards

Incorporate LTV:CAC ratios, cohort retention rates, and segment CLV curves into executive reporting cycles. Tie leadership incentives (e.g., bonuses, compensation targets) to long-term value outcomes. - Cross-Functional CLV Cells

Establish CLV analytics teams staffed by finance, marketing insights, and data engineers. They own CLV modeling, simulation, and distribution across functions. - Monthly CLV Reviews

Monthly orchestration meetings integrate metrics updates, marketing feedback on campaigns, pricing evolution, and retention efforts. Simultaneous adjustment across functions allows dynamic resource allocation. - Capital Allocation Gateways

Projects involving customer-facing decisions—from new products to geographic pullbacks—must include CLV impact assessments in gating criteria. These can also feed into product investment requests and ROI thresholds. - Continuous Learning Loops

CLV models must be updated with actual lifecycle data. Regular recalibration fosters learning from retention behaviors, pricing experiments, churn drivers, and renewal rates—fueling confidence in incremental decision-making.

VI. Caveats and Limitations

CLV, though powerful, is not a cure-all. These caveats merit attention:

- Data Quality: Poorly integrated systems, missing customer identifiers, or inconsistent cohort logic can produce misleading CLV metrics.

- Assumption Risk: Discount rates, churn decay, turnaround behavior—all are model assumptions. Unqualified confidence can mislead investment.

- Narrow Focus: High CLV may chronically favor established segments, leaving growth through new markets or products underserved.

- Over-Targeting Risk: Over-optimizing for short-term yield may harm brand reputation or equity with broader audiences.

Therefore, CLV must be treated with humility—an advanced tool requiring discipline in measurement, calibration, and multi-dimensional insight.

VII. The Influence of Digital Ecosystems

Modern digital ecosystems deliver immense granularity. Every interaction—click, open, referral, session length—is measurable. These dark data provide context for CLV testing, segment behavior, and risk triggers.

However, this scale introduces overfitting risk: spurious correlations may override structural signals. Successful organizations maintain a balance—leveraging high-frequency signals for short-cycle interventions, while retaining medium-term cohort logic for capital allocation and strategic initiatives.

VIII. Ethical and Brand Implications

“CLV”, when viewed through a values lens, also becomes a cultural and ethical marker. Decisions informed by CLV raise questions:

- To what extent should a business monetize a cohort? Is excessive monetization ethical?

- When loyalty programs disproportionately reward high-value customers, does brand equity suffer among moderate spenders?

- When referral bonuses attract opportunists rather than advocates, is brand authenticity compromised?

These considerations demand that CLV strategies incorporate brand and ethical governance, not just financial optimization.

IX. Cross-Functionally Harmonized Governance

A robust operating model to sustain CLV alignment should include:

- Structured Metrics Governance: Common cohort definitions, discount rates, margin allocation, and data timelines maintained under joint sponsorship.

- Integrated Information Architecture: Real-time reporting, defined data lineage (acquisition to LTV), and cross-functional access.

- Quarterly Board Oversight: Board-level dashboards that track digital customer performance and CLV trends as fundamental risk and opportunity signals.

- Ethical Oversight Layer: Cross-functional reviews ensuring CLV-driven decisions don’t undermine customer trust or brand perception.

X. CLV as Strategic Doctrine

When deployed with discipline, CLV becomes more than a metric—it becomes a cultural doctrine. The essential tenets are:

- Time horizon focus: orienting decisions toward lifetime impact rather than short-cycle transactions.

- Cross-functional governance: embedding CLV into finance, marketing, and strategy with shared accountability.

- Continuous recalibration: creating feedback loops that update assumptions and reinforce trust in the metric.

- Ethical stewardship: ensuring customer relationships are respected, brand equity maintained, and monetization balanced.

With that foundation, CLV can guide everything from media budgets and pricing plans to acquisition strategy and market expansion.

Conclusion

In an age where customer relationships define both resilience and revenue, Customer Lifetime Value stands out as an indispensable compass. It unites finance’s need for systematic rigor, marketing’s drive for relevance and engagement, and strategy’s mandate for long-term value creation. When properly modeled, governed, and governed ethically, CLV enables teams to shift from transactional quarterly mindsets to lifetime portfolios—transforming customers into true franchise assets.

For any organization aspiring to mature its performance, CLV is the next frontier. Not just a metric on a dashboard—but a strategic mechanism capable of aligning functions, informing capital allocation, shaping product trajectories, elevating brand meaning, and forging relationships that transcend a single transaction.

Navigating Startup Growth: Adapting Your Operating Model Every Year

If a startup’s journey can be likened to an expedition up Everest, then its operating model is the climbing gear—vital, adaptable, and often revised. In the early stages, founders rely on grit and flexibility. But as companies ascend and attempt to scale, they face a stark and simple truth: yesterday’s systems are rarely fit for tomorrow’s challenges. The premise of this memo is equally stark: your operating model must evolve—consciously and structurally—every 12 months if your company is to scale, thrive, and remain relevant.

This is not a speculative opinion. It is a necessity borne out by economic theory, pattern recognition, operational reality, and the statistical arc of business mortality. According to a 2023 McKinsey report, only 1 in 200 startups make it to $100M in revenue, and even fewer become sustainably profitable. The cliff isn’t due to product failure alone—it’s largely an operational failure to adapt at the right moment. Let’s explore why.

1. The Law of Exponential Complexity

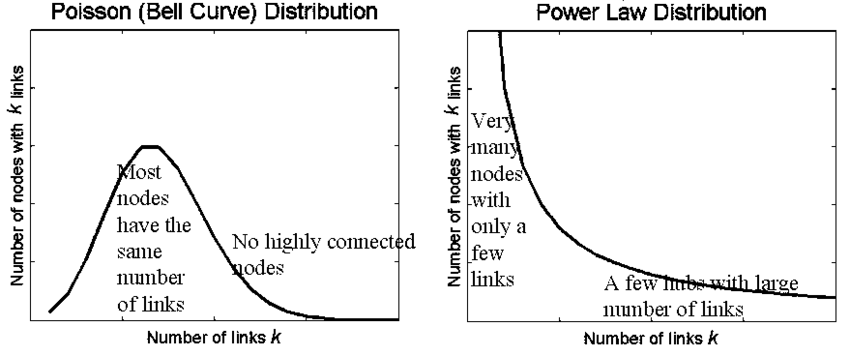

Startups begin with a high signal-to-noise ratio. A few people, one product, and a common purpose. Communication is fluid, decision-making is swift, and adjustments are frequent. But as the team grows from 10 to 50 to 200, each node adds complexity. If you consider the formula for potential communication paths in a group—n(n-1)/2—you’ll find that at 10 employees, there are 45 unique interactions. At 50? That number explodes to 1,225.

This isn’t just theory. Each of those paths represents a potential decision delay, misalignment, or redundancy. Without an intentional redesign of how information flows, how priorities are set, and how accountability is structured, the weight of complexity crushes velocity. An operating model that worked flawlessly in Year 1 becomes a liability in Year 3.

Lesson: The operating model must evolve to actively simplify while the organization expands.

2. The 4 Seasons of Growth

Companies grow in phases, each requiring different operating assumptions. Think of them as seasons:

| Stage | Key Focus | Operating Model Needs |

|---|---|---|

| Start-up | Product-Market Fit | Agile, informal, founder-centric |

| Early Growth | Customer Traction | Lean teams, tight loops, scalable GTM |

| Scale-up | Repeatability | Functional specialization, metrics |

| Expansion | Market Leadership | Cross-functional governance, systems |

At each transition, the company must answer: What must we centralize vs. decentralize? What metrics now matter? Who owns what? A model that optimizes for speed in Year 1 may require guardrails in Year 2. And in Year 3, you may need hierarchy—yes, that dreaded word among startups—to maintain coherence.

Attempting to scale without rethinking the model is akin to flying a Cessna into a hurricane. Many try. Most crash.

3. From Hustle to System: Institutionalizing What Works

Founders often resist operating models because they evoke bureaucracy. But bureaucracy isn’t the issue—entropy is. As the organization grows, systems prevent chaos. A well-crafted operating model does three things:

- Defines governance – who decides what, when, and how.

- Aligns incentives – linking strategy, execution, and rewards.

- Enables measurement – providing real-time feedback on what matters.

Let’s take a practical example. In the early days, a product manager might report directly to the CEO and also collaborate closely with sales. But once you have multiple product lines and a sales org with regional P&Ls, that old model breaks. Now you need Product Ops. You need roadmap arbitration based on capacity planning, not charisma.

Translation: Institutionalize what worked ad hoc by architecting it into systems.

4. Why Every 12 Months? The Velocity Argument

Why not every 24 months? Or every 6? The 12-month cadence is grounded in several interlocking reasons:

- Business cycles: Most companies operate on annual planning rhythms. You set targets, budget resources, and align compensation yearly. The operating model must match that cadence or risk misalignment.

- Cultural absorption: People need time to digest one operating shift before another is introduced. Twelve months is the Goldilocks zone—enough to evaluate results but not too long to become obsolete.

- Market feedback: Every year brings fresh feedback from the market, investors, customers, and competitors. If your operating model doesn’t evolve in step, you’ll lose your edge—like a boxer refusing to switch stances mid-fight.

And then there’s compounding. Like interest on capital, small changes in systems—when made annually—compound dramatically. Optimize decision velocity by 10% annually, and in 5 years, you’ve doubled it. Delay, and you’re crushed by organizational debt.

5. The Operating Model Canvas

To guide this evolution, we recommend using a simplified Operating Model Canvas—a strategic tool that captures the six dimensions that must evolve together:

| Dimension | Key Questions |

|---|---|

| Structure | How are teams organized? What’s centralized? |

| Governance | Who decides what? What’s the escalation path? |

| Process | What are the key workflows? How do they scale? |

| People | Do roles align to strategy? How do we manage talent? |

| Technology | What systems support this stage? Where are the gaps? |

| Metrics | Are we measuring what matters now vs. before? |

Reviewing and recalibrating these dimensions annually ensures that the foundation evolves with the building. The alternative is often misalignment, where strategy runs ahead of execution—or worse, vice versa.

6. Case Studies in Motion: Lessons from the Trenches

a. Slack (Pre-acquisition)

In Year 1, Slack’s operating model emphasized velocity of product feedback. Engineers spoke to users directly, releases shipped weekly, and product decisions were founder-led. But by Year 3, with enterprise adoption rising, the model shifted: compliance, enterprise account teams, and customer success became core to the GTM motion. Without adjusting the operating model to support longer sales cycles and regulated customer needs, Slack could not have grown to a $1B+ revenue engine.

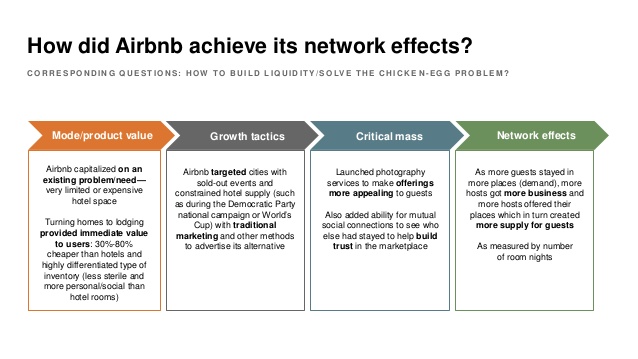

b. Airbnb

Initially, Airbnb’s operating rhythm centered on peer-to-peer UX. But as global regulatory scrutiny mounted, they created entirely new policy, legal, and trust & safety functions—none of which were needed in Year 1. Each year, Airbnb re-evaluated what capabilities were now “core” vs. “context.” That discipline allowed them to survive major downturns (like COVID) and rebound.

c. Stripe

Stripe invested heavily in internal tooling as they scaled. Recognizing that developer experience was not only for customers but also internal teams, they revised their internal operating platforms annually—often before they were broken. The result: a company that scaled to serve millions of businesses without succumbing to the chaos that often plagues hypergrowth.

7. The Cost of Inertia

Aging operating models extract a hidden tax. They confuse new hires, slow decisions, demoralize high performers, and inflate costs. Worse, they signal stagnation. In a landscape where capital efficiency is paramount (as underscored in post-2022 venture dynamics), bloated operating models are a death knell.

Consider this: According to Bessemer Venture Partners, top quartile SaaS companies show Rule of 40 compliance with fewer than 300 employees per $100M of ARR. Those that don’t? Often have twice the headcount with half the profitability—trapped in models that no longer fit their stage.

8. How to Operationalize the 12-Month Reset

For practical implementation, I suggest a 12-month Operating Model Review Cycle:

| Month | Focus Area |

|---|---|

| Jan | Strategic planning finalization |

| Feb | Gap analysis of current model |

| Mar | Cross-functional feedback loop |

| Apr | Draft new operating model vNext |

| May | Review with Exec Team |

| Jun | Pilot model changes |

| Jul | Refine and communicate broadly |

| Aug | Train managers on new structures |

| Sep | Integrate into budget planning |

| Oct | Lock model into FY plan |

| Nov | Run simulations/test governance |

| Dec | Prepare for January launch |

This cycle ensures that your org model does not lag behind your strategic ambition. It also sends a powerful cultural signal: we evolve intentionally, not reactively.

Conclusion: Be the Architect, Not the Archaeologist

Every successful company is, at some level, a systems company. Apple is as much about its supply chain as its design. Amazon is a masterclass in operating cadence. And Salesforce didn’t win by having a better CRM—it won by continuously evolving its go-to-market and operating structure.

To scale, you must be the architect of your company’s operating future—not an archaeologist digging up decisions made when the world was simpler.

So I leave you with this conviction: operating models are not carved in stone—they are coded in cycles. And the companies that win are those that rewrite that code every 12 months—with courage, with clarity, and with conviction.

Bias and Error: Human and Organizational Tradeoff

“I spent a lifetime trying to avoid my own mental biases. A.) I rub my own nose into my own mistakes. B.) I try and keep it simple and fundamental as much as I can. And, I like the engineering concept of a margin of safety. I’m a very blocking and tackling kind of thinker. I just try to avoid being stupid. I have a way of handling a lot of problems — I put them in what I call my ‘too hard pile,’ and just leave them there. I’m not trying to succeed in my ‘too hard pile.’” : Charlie Munger — 2020 CalTech Distinguished Alumni Award interview

Bias is a disproportionate weight in favor of or against an idea or thing, usually in a way that is closed-minded, prejudicial, or unfair. Biases can be innate or learned. People may develop biases for or against an individual, a group, or a belief. In science and engineering, a bias is a systematic error. Statistical bias results from an unfair sampling of a population, or from an estimation process that does not give accurate results on average.

Error refers to a outcome that is different from reality within the context of the objective function that is being pursued.

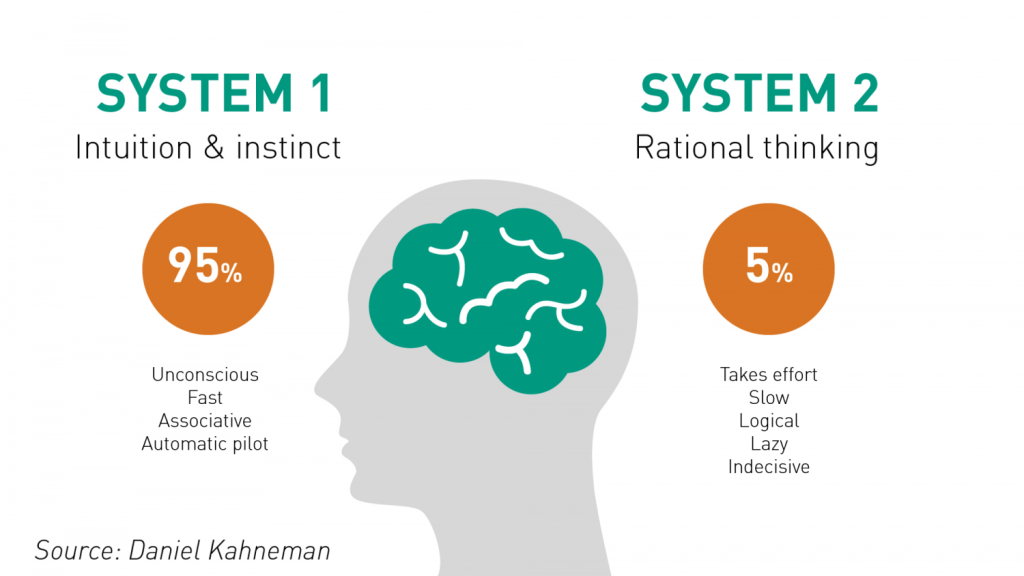

Thus, I would like to think that the Bias is a process that might lead to an Error. However, that is not always the case. There are instances where a bias might get you to an accurate or close to an accurate result. Is having a biased framework always a bad thing? That is not always the case. From an evolutionary standpoint, humans have progressed along the dimension of making rapid judgements – and much of them stemming from experience and their exposure to elements in society. Rapid judgements are typified under the System 1 judgement (Kahneman, Tversky) which allows bias and heuristic to commingle to effectively arrive at intuitive decision outcomes.

And again, the decision framework constitutes a continually active process in how humans or/and organizations execute upon their goals. It is largely an emotional response but could just as well be an automated response to a certain stimulus. However, there is a danger prevalent in System 1 thinking: it might lead one to comfortably head toward an outcome that is seemingly intuitive, but the actual result might be significantly different and that would lead to an error in the judgement. In math, you often hear the problem of induction which establishes that your understanding of a future outcome relies on the continuity of the past outcomes, and that is an errant way of thinking although it still represents a useful tool for us to advance toward solutions.

System 2 judgement emerges as another means to temper the more significant variabilities associated with System 1 thinking. System 2 thinking represents a more deliberate approach which leads to a more careful construct of rationale and thought. It is a system that slows down the decision making since it explores the logic, the assumptions, and how the framework tightly fits together to test contexts. There are a more lot more things at work wherein the person or the organization has to invest the time, focus the efforts and amplify the concentration around the problem that has to be wrestled with. This is also the process where you search for biases that might be at play and be able to minimize or remove that altogether. Thus, each of the two Systems judgement represents two different patterns of thinking: rapid, more variable and more error prone outcomes vs. slow, stable and less error prone outcomes.

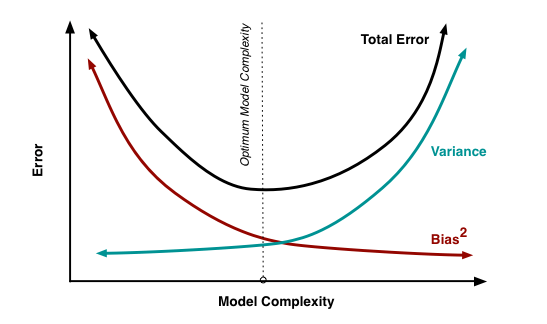

So let us revisit the Bias vs. Variance tradeoff. The idea is that the more bias you bring to address a problem, there is less variance in the aggregate. That does not mean that you are accurate. It only means that there is less variance in the set of outcomes, even if all of the outcomes are materially wrong. But it limits the variance since the bias enforces a constraint in the hypotheses space leading to a smaller and closely knit set of probabilistic outcomes. If you were to remove the constraints in the hypotheses space – namely, you remove bias in the decision framework – well, you are faced with a significant number of possibilities that would result in a larger spread of outcomes. With that said, the expected value of those outcomes might actually be closer to reality, despite the variance – than a framework decided upon by applying heuristic or operating in a bias mode.

So how do we decide then? Jeff Bezos had mentioned something that I recall: some decisions are one-way street and some are two-way. In other words, there are some decisions that cannot be undone, for good or for bad. It is a wise man who is able to anticipate that early on to decide what system one needs to pursue. An organization makes a few big and important decisions, and a lot of small decisions. Identify the big ones and spend oodles of time and encourage a diverse set of input to work through those decisions at a sufficiently high level of detail. When I personally craft rolling operating models, it serves a strategic purpose that might sit on shifting sands. That is perfectly okay! But it is critical to evaluate those big decisions since the crux of the effectiveness of the strategy and its concomitant quantitative representation rests upon those big decisions. Cutting corners can lead to disaster or an unforgiving result!

I will focus on the big whale decisions now. I will assume, for the sake of expediency, that the series of small decisions, in the aggregate or by itself, will not sufficiently be large enough that it would take us over the precipice. (It is also important however to examine the possibility that a series of small decisions can lead to a more holistic unintended emergent outcome that might have a whale effect: we come across that in complexity theory that I have already touched on in a set of previous articles).

Cognitive Biases are the biggest mea culpas that one needs to worry about. Some of the more common biases are confirmation bias, attribution bias, the halo effect, the rule of anchoring, the framing of the problem, and status quo bias. There are other cognition biases at play, but the ones listed above are common in planning and execution. It is imperative that these biases be forcibly peeled off while formulating a strategy toward problem solving.

But then there are also the statistical biases that one needs to be wary of. How we select data or selection bias plays a big role in validating information. In fact, if there are underlying statistical biases, the validity of the information is questionable. Then there are other strains of statistical biases: the forecast bias which is the natural tendency to be overtly optimistic or pessimistic without any substantive evidence to support one or the other case. Sometimes how the information is presented: visually or in tabular format – can lead to sins of the error of omission and commission leading the organization and judgement down paths that are unwarranted and just plain wrong. Thus, it is important to be aware of how statistical biases come into play to sabotage your decision framework.

One of the finest illustrations of misjudgment has been laid out by Charlie Munger. Here is the excerpt link : https://fs.blog/great-talks/psychology-human-misjudgment/ He lays out a very comprehensive 25 Biases that ail decision making. Once again, stripping biases do not necessarily result in accuracy — it increases the variability of outcomes that might be clustered around a mean that might be closer to accuracy than otherwise.

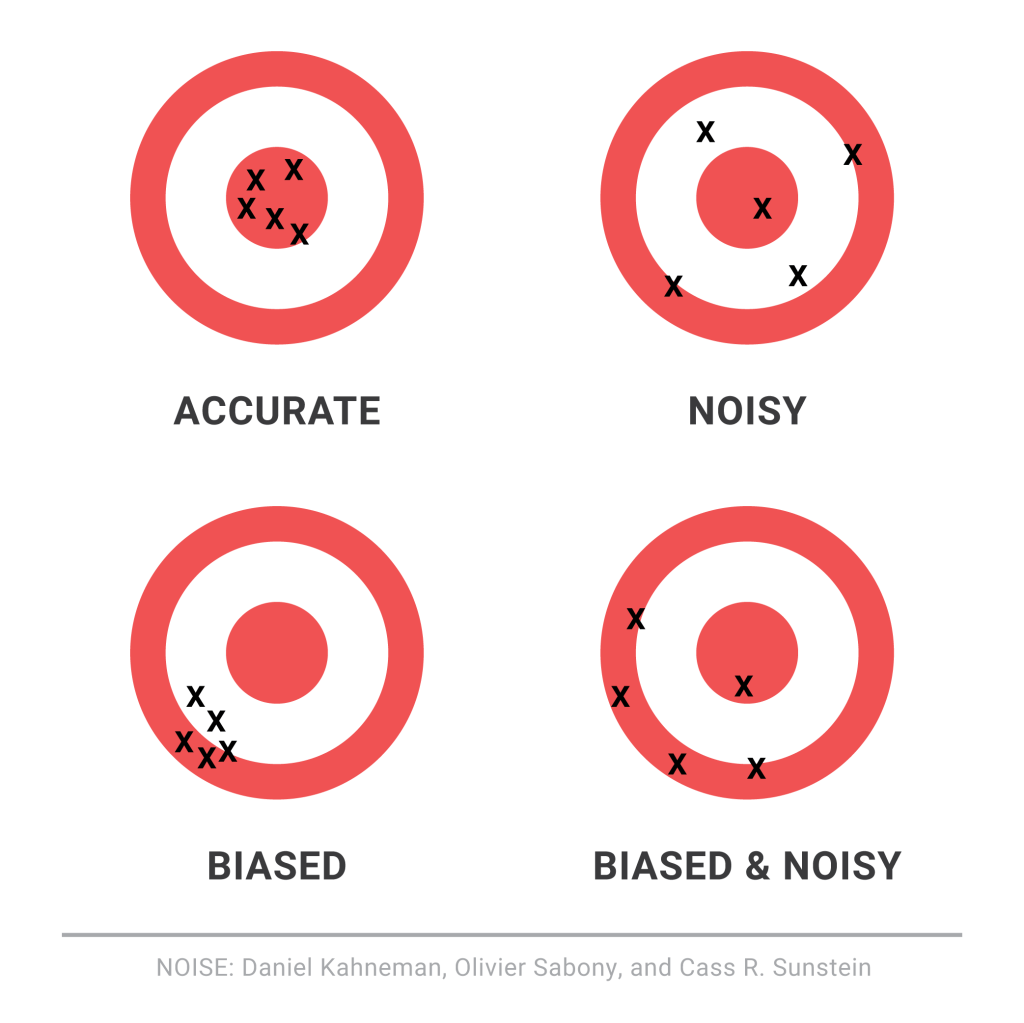

Variability is Noise. We do not know a priori what the expected mean is. We are close, but not quite. There is noise or a whole set of outcomes around the mean. Viewing things closer to the ground versus higher would still create a likelihood of accepting a false hypothesis or rejecting a true one. Noise is extremely hard to sift through, but how you can sift through the noise to arrive at those signals that are determining factors, is critical to organization success. To get to this territory, we have eliminated the cognitive and statistical biases. Now is the search for the signal. What do we do then? An increase in noise impairs accuracy. To improve accuracy, you either reduce noise or figure out those indicators that signal an accurate measure.

This is where algorithmic thinking comes into play. You start establishing well tested algorithms in specific use cases and cross-validate that across a large set of experiments or scenarios. It has been proved that algorithmic tools are, in the aggregate, superior to human judgement – since it systematically can surface causal and correlative relationships. Furthermore, special tools like principal component analysis and factory analysis can incorporate a large input variable set and establish the patterns that would be impregnable for even System 2 mindset to comprehend. This will bring decision making toward the signal variants and thus fortify decision making.

The final element is to assess the time commitment required to go through all the stages. Given infinite time and resources, there is always a high likelihood of arriving at those signals that are material for sound decision making. Alas, the reality of life does not play well to that assumption! Time and resources are constraints … so one must make do with sub-optimal decision making and establish a cutoff point wherein the benefits outweigh the risks of looking for another alternative. That comes down to the realm of judgements. While George Stigler, a Nobel Laureate in Economics, introduce search optimization in fixed sequential search – a more concrete example has been illustrated in “Algorithms to Live By” by Christian & Griffiths. They suggested an holy grail response: 37% is the accurate answer. In other words, you would reach a suboptimal decision by ensuring that you have explored up to 37% of your estimated maximum effort. While the estimated maximum effort is quite ambiguous and afflicted with all of the elements of bias (cognitive and statistical), the best thinking is to be as honest as possible to assess that effort and then draw your search threshold cutoff.

An important element of leadership is about making calls. Good calls, not necessarily the best calls! Calls weighing all possible circumstances that one can, being aware of the biases, bringing in a diverse set of knowledge and opinions, falling back upon agnostic tools in statistics, and knowing when it is appropriate to have learnt enough to pull the trigger. And it is important to cascade the principles of decision making and the underlying complexity into and across the organization.

Model Thinking

| Model Framework |

The fundamental tenet of theory is the concept of “empiria“. Empiria refers to our observations. Based on observations, scientists and researchers posit a theory – it is part of scientific realism.

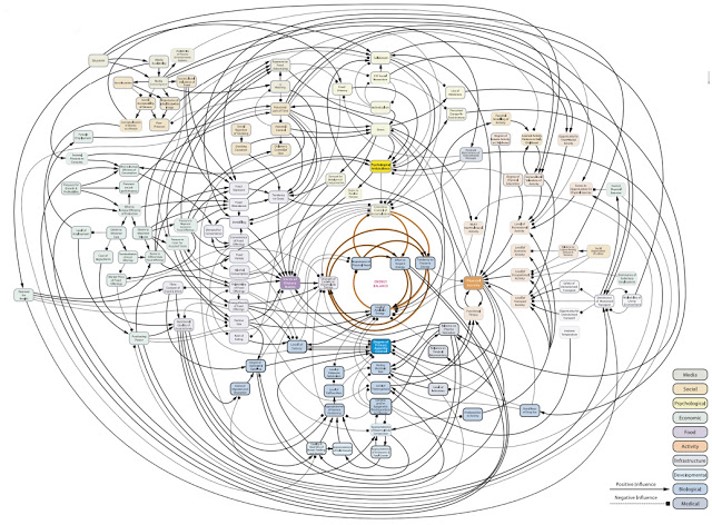

A scientific model is a causal explanation of how variables interact to produce a phenomenon, usually linearly organized. A model is a simplified map consisting of a few, primary variables that is gauged to have the most explanatory powers for the phenomenon being observed. We discussed Complex Physical Systems and Complex Adaptive Systems early on this chapter. It is relatively easier to map CPS to models than CAS, largely because models become very unwieldy as it starts to internalize more variables and if those variables have volumes of interaction between them. A simple analogy would be the use of multiple regression models: when you have a number of independent variables that interact strongly between each other, autocorrelation errors occur, and the model is not stable or does not have predictive value.

Research projects generally tend to either look at a case study or alternatively, they might describe a number of similar cases that are logically grouped together. Constructing a simple model that can be general and applied to many instances is difficult, if not impossible. Variables are subject to a researcher’s lack of understanding of the variable or the volatility of the variable. What further accentuates the problem is that the researcher misses on the interaction of how the variables play against one another and the resultant impact on the system. Thus, our understanding of our system can be done through some sort of model mechanics but, yet we share the common belief that the task of building out a model to provide all of the explanatory answers are difficult, if not impossible. Despite our understanding of our limitations of modeling, we still develop frameworks and artifact models because we sense in it a tool or set of indispensable tools to transmit the results of research to practical use cases. We boldly generalize our findings from empiria into general models that we hope will explain empiria best. And let us be mindful that it is possible – more so in the CAS systems than CPS that we might have multiple models that would fight over their explanatory powers simply because of the vagaries of uncertainty and stochastic variations.

Popper says: “Science does not rest upon rock-bottom. The bold structure of its theories rises, as it were, above a swamp. It is like a building erected on piles. The piles are driven down from above into the swamp, but not down to any natural or ‘given’ base; and when we cease our attempts to drive our piles into a deeper layer, it is not because we have reached firm ground. We simply stop when we are satisfied that they are firm enough to carry the structure, at least for the time being”. This leads to the satisficing solution: if a model can choose the least number of variables to explain the greatest amount of variations, the model is relatively better than other models that would select more variables to explain the same. In addition, there is always a cost-benefit analysis to be taken into consideration: if we add x number of variables to explain variation in the outcome but it is not meaningfully different than variables less than x, then one would want to fall back on the less-variable model because it is less costly to maintain.

Researchers must address three key elements in the model: time, variation and uncertainty. How do we craft a model which reflects the impact of time on the variables and the outcome? How to present variations in the model? Different variables might vary differently independent of one another. How do we present the deviation of the data in a parlance that allows us to make meaningful conclusions regarding the impact of the variations on the outcome? Finally, does the data that is being considered are actual or proxy data? Are the observations approximate? How do we thus draw the model to incorporate the fuzziness: would confidence intervals on the findings be good enough?

Two other equally other concepts in model design is important: Descriptive Modeling and Normative Modeling.

Descriptive models aim to explain the phenomenon. It is bounded by that goal and that goal only.

There are certain types of explanations that they fall back on: explain by looking at data from the past and attempting to draw a cause and effect relationship. If the researcher is able to draw a complete cause and effect relationship that meets the test of time and independent tests to replicate the results, then the causality turns into law for the limited use-case or the phenomenon being explained. Another explanation method is to draw upon context: explaining a phenomenon by looking at the function that the activity fulfills in its context. For example, a dog barks at a stranger to secure its territory and protect the home. The third and more interesting type of explanation is generally called intentional explanation: the variables work together to serve a specific purpose and the researcher determines that purpose and thus, reverse engineers the understanding of the phenomenon by understanding the purpose and how the variables conform to achieve that purpose.

This last element also leads us to thinking through the other method of modeling – namely, normative modeling. Normative modeling differs from descriptive modeling because the target is not to simply just gather facts to explain a phenomenon, but rather to figure out how to improve or change the phenomenon toward a desirable state. The challenge, as you might have already perceived, is that the subjective shadow looms high and long and the ultimate finding in what would be a normative model could essentially be a teleological representation or self-fulfilling prophecy of the researcher in action. While this is relatively more welcome in a descriptive world since subjectivism is diffused among a larger group that yields one solution, it is not the best in a normative world since variation of opinions that reflect biases can pose a problem.

How do we create a representative model of a phenomenon? First, we weigh if the phenomenon is to be understood as a mere explanation or to extend it to incorporate our normative spin on the phenomenon itself. It is often the case that we might have to craft different models and then weigh one against the other that best represents how the model can be explained. Some of the methods are fairly simple as in bringing diverse opinions to a table and then agreeing upon one specific model. The advantage of such an approach is that it provides a degree of objectivism in the model – at least in so far as it removes the divergent subjectivity that weaves into the various models. Other alternative is to do value analysis which is a mathematical method where the selection of the model is carried out in stages. You define the criteria of the selection and then the importance of the goal (if that be a normative model). Once all of the participants have a general agreement, then you have the makings of a model. The final method is to incorporate all all of the outliers and the data points in the phenomenon that the model seeks to explain and then offer a shared belief into those salient features in the model that would be best to apply to gain information of the phenomenon in a predictable manner.

There are various languages that are used for modeling:

Written Language refers to the natural language description of the model. If price of butter goes up, the quantity demanded of the butter will go down. Written language models can be used effectively to inform all of the other types of models that follow below. It often goes by the name of “qualitative” research, although we find that a bit limiting. Just a simple statement like – This model approximately reflects the behavior of people living in a dense environment …” could qualify as a written language model that seeks to shed light on the object being studied.

Icon Models refer to a pictorial representation and probably the earliest form of model making. It seeks to only qualify those contours or shapes or colors that are most interesting and relevant to the object being studied. The idea of icon models is to pictorially abstract the main elements to provide a working understanding of the object being studied.

Topological Models refer to how the variables are placed with respect to one another and thus helps in creating a classification or taxonomy of the model. Once can have logical trees, class trees, Venn diagrams, and other imaginative pictorial representation of fields to further shed light on the object being studied. In fact, pictorial representations must abide by constant scale, direction and placements. In other words, if the variables are placed on a different scale on different maps, it would be hard to draw logical conclusions by sight alone. In addition, if the placements are at different axis in different maps or have different vectors, it is hard to make comparisons and arrive at a shared consensus and a logical end result.

Arithmetic Models are what we generally fall back on most. The data is measured with an arithmetic scale. It is done via tables, equations or flow diagrams. The nice thing about arithmetic models is that you can show multiple dimensions which is not possible with other modeling languages. Hence, the robustness and the general applicability of such models are huge and thus is widely used as a key language to modeling.

Analogous Models refer to crafting explanations using the power of analogy. For example, when we talk about waves – we could be talking of light waves, radio waves, historical waves, etc. These metaphoric representations can be used to explain phenomenon, but at best, the explanatory power is nebulous, and it would be difficult to explain the variations and uncertainties between two analogous models. However, it still is used to transmit information quickly through verbal expressions like – “Similarly”, “Equivalently”, “Looks like ..” etc. In fact, extrapolation is a widely used method in modeling and we would ascertain this as part of the analogous model to a great extent. That is because we time-box the variables in the analogous model to one instance and the extrapolated model to another instance and we tie them up with mathematical equations.