Blog Archives

Transforming Finance: From ERP to Real-Time Decision Making

There was a time when the role of the CFO could be summarized with a handful of verbs: report, reconcile, allocate, forecast. In the 20th century, the finance office was a bastion of structure and control. The CFO was the high priest of compliance and the gatekeeper of capital. The systems were linear, the rhythms were quarterly, and the decisions were based on historical truths.

That era has passed. In its place emerges the Digital CFO 3.0 – a new kind of enterprise leader who moves beyond control towers and static spreadsheets to architect digital infrastructure, orchestrate intelligent systems, and enable predictive, adaptive, and real-time decision-making across the enterprise.

This is not a change in tools. It is a change in mindset, muscle, and mandate.

The Digital CFO 3.0 is not just a steward of financial truth. They are a strategic systems architect, a data supply chain engineer, and a design thinker for the cognitive enterprise. Their domain now includes APIs, cloud data lakes, process automation, AI-enabled forecasting, and trust-layer governance models. They must reimagine the finance function not as a back-office cost center, but as the neural core of a learning organization.

Let us explore the core principles, capabilities, and operating architecture that define this new role, and how today’s finance leaders must prepare to build the infrastructure of the future enterprise.

1. From Monolithic ERP to Modular Intelligence

Traditional finance infrastructure was built on monolithic ERP systems – massive, integrated, but inflexible. Every upgrade was painful. Data latency was high. Insight was slow.

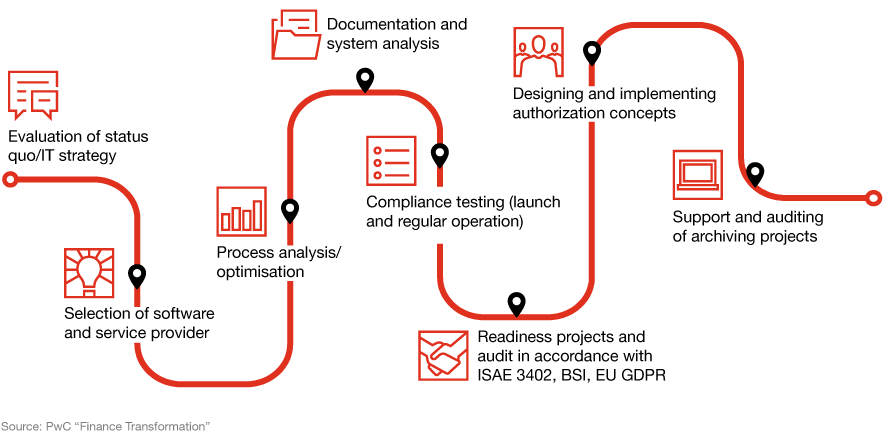

The Digital CFO 3.0 shifts toward a modular, composable architecture. Finance tools are API-connected, event-driven, and cloud-native. Data moves in real time through finance operations, from procure-to-pay to order-to-cash.

- Core systems remain but are surrounded by microservices for specific tasks: forecasting, scenario modeling, spend analytics, compliance monitoring.

- Data lakes and warehouses serve as integration layers, decoupling applications from reporting.

- AI and ML modules plug into these environments to generate insights on demand.

This architecture enables agility. New use cases can be spun up quickly. Forecasting models can be retrained in hours, not months. Finance becomes a responsive, intelligent grid rather than a transactional pipe.

2. Finance as a Real-Time Operating System

In legacy models, finance operated in batch mode: monthly closes, quarterly forecasts, annual planning. But the modern enterprise operates in real time. Markets shift hourly. Customer behavior changes daily. Capital decisions must respond accordingly.

The Digital CFO builds a real-time finance engine:

- Continuous Close: Transactions are reconciled daily, not monthly. Variances are flagged immediately. The books are always nearly closed.

- Rolling Forecasting: Plans update with each new signal – not by calendar, but by context.

- Embedded Analytics: Metrics travel with the business – inside CRM, procurement, inventory, and workforce systems.

- Streaming KPIs: Finance watches the enterprise like a heart monitor, not a photograph.

This changes how decisions are made. Instead of waiting for reports, leaders ask questions in the flow of business – and get answers in seconds.

3. Trust by Design: The New Governance Layer

As data velocity increases, so does the risk of error, bias, and misinterpretation. The CFO has always been a guardian of trust. But for the Digital CFO 3.0, this mandate extends to the digital trust layer:

- Data Lineage: Every number is traceable. Every transformation is logged.

- Model Governance: AI models used in finance must be explainable, auditable, and ethical.

- Access Control: Fine-grained permissions ensure only the right people see the right numbers.

- Validation Rules: Embedded in pipelines to flag anomalies before they reach the dashboard.

Trust is not a byproduct of strong reporting. It is an outcome of intentional design.

4. Orchestrating the Intelligent Workflow

In the digital enterprise, no team operates in isolation. Sales, operations, procurement, HR are interconnected. The Digital CFO 3.0 builds infrastructure to orchestrate intelligent workflows across silos.

- AP automation connects with vendor portals and treasury systems.

- Forecast adjustments trigger alerts to sourcing and demand planning teams.

- Employee cost changes ripple through headcount plans and productivity dashboards.

This orchestration requires more than software. It demands process choreography and data interoperability. The CFO becomes the conductor of a distributed, dynamic finance system.

5. Redesigning Talent for a Cognitive Finance Team

Digital infrastructure is only as powerful as the team that runs it. The finance org of the future looks different:

- Analysts become insight designers, curating stories from signals.

- Controllers become data quality stewards.

- FP&A teams become simulation strategists.

- Finance business partners become embedded value engineers.

The Digital CFO invests in technical fluency, data storytelling, and systems thinking. Upskilling is continuous. Learning velocity becomes a core KPI.

6. From Reporting the Past to Architecting the Future

Ultimately, the Digital CFO 3.0 is not building systems to describe yesterday. They are designing infrastructure to anticipate tomorrow:

- Capex investments are modeled across geopolitical scenarios.

- ESG metrics are embedded into supplier scoring and budget cycles.

- Strategic choices are evaluated with real option models and probabilistic simulations.

- M&A integration plans are automated, with finance playbooks triggered by transaction type.

The finance function becomes a predictive nerve center, informing everything from product pricing to market entry.

Conclusion: The CFO as Enterprise Architect

The shift to Digital CFO 2.0 is not optional. It is inevitable. Markets are faster. Technology is smarter. Stakeholders expect more. What was once a support function is now a strategic command center.

This is not about buying tools. It is about designing an operating system for the enterprise that is intelligent, adaptive, and deeply aligned with value creation.

The future CFO does not just report results. They engineer outcomes. They do not just forecast growth. They architect the infrastructure to make it happen.

How Strategic CFOs Drive Sustainable Growth and Change

When people ask me what the most critical relationship in a company really is, I always say it’s the one between the CEO and the CFO. And no, I am not being flippant. In my thirty years helping companies manage growth, navigate crises, and execute strategic shifts, the moments that most often determine success or spiraled failure often rests on how tightly the CEO and CFO operate together. One sets a vision. The other turns aspiration into action. Alone, each has influence; together, they can transform the business.

Transformation, after all, is not a project. It is a culture shift, a strategic pivot, a redefinition of operating behaviors. It’s more art than engineering and more people than process. And at the heart of it lies a fundamental tension: You need ambition, yet you must manage risk. You need speed, but you cannot abandon discipline. You must pursue new business models while preserving your legacy foundations. In short, you need to build simultaneously on forward momentum and backward certainty.

That complexity is where the strategic CFO becomes indispensable. The CFO’s job is not just to count beans, it’s to clear the ground where new plants can grow. To unlock capital without unleashing chaos. To balance accountable rigor with growth ambition. To design transformation from the numbers up, not just hammer it into the planning cycle. When this role is fulfilled, the CEO finds their most trusted confidante, collaborator, and catalyst.

Think of it this way. A CEO paints a vision: We must double revenue, globalize our go-to-market, pivot into new verticals, revamp the product, or embrace digital. It sounds exciting. It feels bold. But without a financial foundation, it becomes delusional. Does the company have the cash runway? Can the old cost base support the new trajectory? Are incentives aligned? Are the systems ready? Will the board nod or push back? Who is accountable if sales forecast misses or an integration falters? A CFO’s strategic role is to bring those questions forward not cynically, but constructively—so the ambition becomes executable.

The best CEOs I’ve worked with know this partnership instinctively. They build strategy as much with the CFO as with the head of product or sales. They reward honest challenge, not blind consensus. They request dashboards that update daily, not glossy decks that live in PowerPoint. They ask, “What happens to operating income if adoption slows? Can we reverse full-time hiring if needed? Which assumptions unlock upside with minimal downside?” Then they listen. And change. That’s how transformation becomes durable.

Let me share a story. A leader I admire embarked on a bold plan: triple revenue in two years through international expansion and a new channel model. The exec team loved the ambition. Investors cheered. But the CFO, without hesitation, did not say no. She said let us break it down. Suppose it costs $30 million to build international operations, $12 million to fund channel enablement, plus incremental headcount, marketing expenses, R&D coordination, and overhead. Let us stress test the plan. What if licensing stalls? What if fulfillment issues delay launches? What if cross-border tax burdens permanently drag down the margin?

The CEO wanted the bold headline number. But together, they translated it into executable modules. They set up rolling gates: a $5 million pilot, learn, fund next $10 million, learn, and so on. They built exit clauses. They aligned incentives so teams could pivot without losing credibility. They also built redundancy into systems and analytics, with daily data and optionality-based budgeting. The CEO had the vision, but the CFO gave it a frame. That is partnership.

That framing role extends beyond capital structure or P&L. It bleeds into operating rhythm. The strategic CFO becomes the architect of transformation cadence. They design how weekly, monthly, and quarterly look and feel. They align incentive schemes so that geography may outperform globally while still holding central teams accountable. They align finance, people, product, and GTM teams to shared performance metrics—not top-level vanity metrics, but actionable ones: user engagement, cost per new customer, onboarding latency, support burden, renewal velocity. They ensure data is not stashed in silos. They make it usable, trusted, visible. Because transformation is only as effective as your ability to measure missteps, iterate, and learn.

This is why I say the CFO becomes a strategic weapon: a lever for insight, integration, and investment.

Boards understand this too, especially when it is too late. They see CEOs who talk of digital transformation while still approving global headcount hikes. They see operating legacy systems still dragging FY ‘Digital 2.0’ ambition. They see growth funded, but debt rising with little structural benefit. In those moments, they turn to the CFO. The board does not ask the CFO if they can deliver the numbers. They ask whether the CEO can. They ask, “What’s the downside exposure? What are the guardrails? Who is accountable? How long will transformation slow profitability? And can we reverse if needed?”

That board confidence, when positive, is not accidental. It comes from a CFO who built that trust, not by polishing a spreadsheet, but by building strategy together, testing assumptions early, and designing transformation as a financial system.

Indeed, transformation without control is just creative destruction. And while disruption may be trendy, few businesses survive without solid footing. The CFO ensures that disruption does not become destruction. That investments scale with impact. That flexibility is funded. That culture is not ignored. That when exceptions arise, they do not unravel behaviors, but refocus teams.

This is often unseen. Because finance is a support function, not a front-facing one. But consider this: it is finance that approves the first contract. Finance assists in setting the commission structure that defines behavior. Finance sets the credit policy, capital constraints, and invoice timing, and all of these have strategic logic. A CFO who treats each as a tactical lever becomes the heart of transformation.

Take forecasting. Transformation cannot run on backward-moving averages. Yet too many companies rely on year-over-year rates, lagged signals, and static targets. The strategic CFO resurrects forecasting. They bring forward leading indicators of product usage, sales pipeline, supply chain velocity. They reframe forecasts as living systems. We see a dip? We call a pivot meeting. We see high churn? We call the product team. We see hiring cost creep? We call HR. Forewarned is forearmed. That is transformation in flight.

On the capital front, the CFO becomes a barbell strategist. They pair patient growth funding with disciplined structure. They build in fields of optionality: reserves for opportunistic moves, caps on unfunded headcount, staged deployment, and scalable contracts. They calibrate pricing experiments. They design customer acquisition levers with off ramps. They ensure that at every step of change, you can set a gear to reverse—without losing momentum, but with discipline.

And they align people. Transformation hinges on mindset. In fast-moving companies, people often move faster than they think. Great leaders know this. The strategic CFO builds transparency into compensation. They design equity vesting tied to transformation metrics. They design long-term incentives around cross-functional execution. They also design local authority within discipline. Give leaders autonomy, but align them to the rhythm of finance. Even the best strategy dies when every decision is a global approval. Optionality must scale with coordination.

Risk management transforms too. In the past, the CFO’s role in transformation was to shield operations from political turbulence. Today, it is to internally amplify controlled disruption. That means modeling volatility with confidence. Scenario modeling under market shock, regulatory shift, customer segmentation drift. Not just building firewalls, but designing escape ramps and counterweights. A transformation CFO builds risk into transformation—but as a system constraint to be managed, not a gate to prevent ambition.

I once had a CEO tell me they felt alone when delivering digital transformation. HR was not aligned. Product was moving too slowly. Sales was pushing legacy business harder. The CFO had built a bridge. They brought HR, legal, sales, and marketing into weekly update sessions, each with agreed metrics. They brokered resolutions. They surfaced trade-offs confidently. They pressed accountability floor—not blame, but clarity. That is partnership. That is transformation armor.

Transformation also triggers cultural tectonics. And every tectonic shift features friction zones—power renegotiation, process realignment, work redesign. Without financial discipline, politics wins. Mistrust builds. Change derails. The strategic CFO intervenes not as a policeman, but as an arbiter of fairness: If people are asked to stretch, show them the ROI. If processes migrate, show them the rationale. If roles shift, unpack the logic. Maintaining trust alignment during transformation is as important as securing funding.

The ability to align culture, capital, cadence, and accountability around a single north star—that is the strategic CFO’s domain.

And there is another hidden benefit: the CFO’s posture sets the tone for transformation maturity. CFOs who co-create, co-own, and co-pivot build transformation muscle. Those companies that learn together scale transformation together.

I once wrote that investors will forgive a miss if the learning loops are obvious. That is also true inside the company. When a CEO and CFO are aligned, and the CFO is the first to acknowledge what is not working to expectations, when pivots are driven by data rather than ego, that establishes the foundation for resilient leadership. That is how companies rebuild trust in growth every quarter. That is how transformation becomes a norm.

If there is a fear inside the CFO community, it is the fear of being visible. A CFO may believe that financial success is best served quietly. But the moment they step confidently into transformation, they change that dynamic. They say: Yes, we own the books. But we also own the roadmap. Yes, we manage the tail risk. But we also amplify the tail opportunity. That mindset is contagious. It builds confidence across the company and among investors. That shift in posture is more valuable than any forecast.

So let me say it again. Strategy is not a plan. Mechanics do not make execution. Systems do. And at the junction of vision and execution, between boardroom and frontline, stands the CFO. When transformation is on the table, the CFO walks that table from end to end. They make sure the chairs are aligned. The evidence is available. The accountability is shared. The capital is allocated, measured, and adapted.

This is why I refer to the CFO as the CEO’s most important ally. Not simply a confidante. Not just a number-cruncher. A partner in purpose. A designer of execution. A steward of transformation. Which is why, if you are a CFO reading this, I encourage you: step forward. You do not need permission to rethink transformation. You need conviction to shape it. And if you can build clarity around capital, establish a cadence for metrics, align incentives, and implement systems for governance, you will make your CEO’s job easier. You will elevate your entire company. You will unlock optionality not just for tomorrow, but for the years that follow. Because in the end, true transformation is not a moment. It is a movement. And the CFO, when prepared, can lead it.

Bias and Error: Human and Organizational Tradeoff

“I spent a lifetime trying to avoid my own mental biases. A.) I rub my own nose into my own mistakes. B.) I try and keep it simple and fundamental as much as I can. And, I like the engineering concept of a margin of safety. I’m a very blocking and tackling kind of thinker. I just try to avoid being stupid. I have a way of handling a lot of problems — I put them in what I call my ‘too hard pile,’ and just leave them there. I’m not trying to succeed in my ‘too hard pile.’” : Charlie Munger — 2020 CalTech Distinguished Alumni Award interview

Bias is a disproportionate weight in favor of or against an idea or thing, usually in a way that is closed-minded, prejudicial, or unfair. Biases can be innate or learned. People may develop biases for or against an individual, a group, or a belief. In science and engineering, a bias is a systematic error. Statistical bias results from an unfair sampling of a population, or from an estimation process that does not give accurate results on average.

Error refers to a outcome that is different from reality within the context of the objective function that is being pursued.

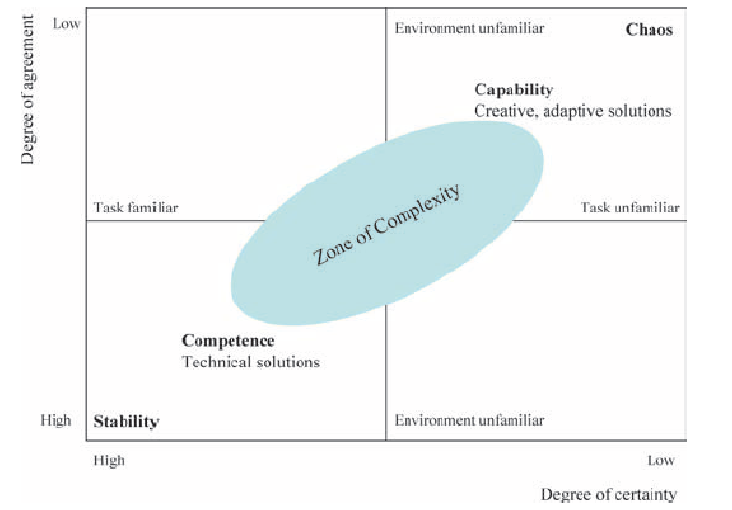

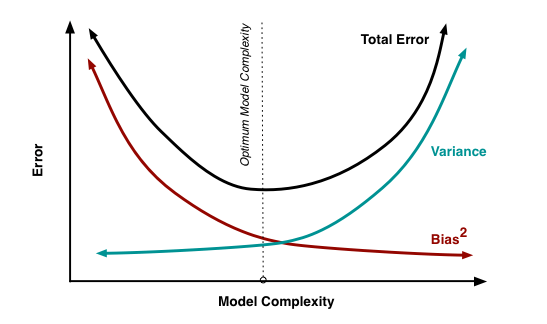

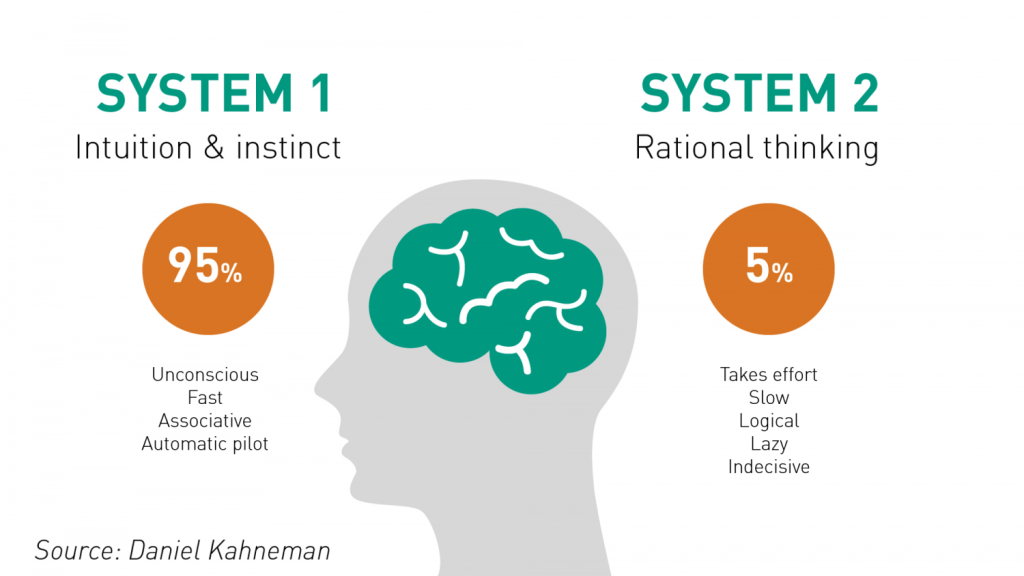

Thus, I would like to think that the Bias is a process that might lead to an Error. However, that is not always the case. There are instances where a bias might get you to an accurate or close to an accurate result. Is having a biased framework always a bad thing? That is not always the case. From an evolutionary standpoint, humans have progressed along the dimension of making rapid judgements – and much of them stemming from experience and their exposure to elements in society. Rapid judgements are typified under the System 1 judgement (Kahneman, Tversky) which allows bias and heuristic to commingle to effectively arrive at intuitive decision outcomes.

And again, the decision framework constitutes a continually active process in how humans or/and organizations execute upon their goals. It is largely an emotional response but could just as well be an automated response to a certain stimulus. However, there is a danger prevalent in System 1 thinking: it might lead one to comfortably head toward an outcome that is seemingly intuitive, but the actual result might be significantly different and that would lead to an error in the judgement. In math, you often hear the problem of induction which establishes that your understanding of a future outcome relies on the continuity of the past outcomes, and that is an errant way of thinking although it still represents a useful tool for us to advance toward solutions.

System 2 judgement emerges as another means to temper the more significant variabilities associated with System 1 thinking. System 2 thinking represents a more deliberate approach which leads to a more careful construct of rationale and thought. It is a system that slows down the decision making since it explores the logic, the assumptions, and how the framework tightly fits together to test contexts. There are a more lot more things at work wherein the person or the organization has to invest the time, focus the efforts and amplify the concentration around the problem that has to be wrestled with. This is also the process where you search for biases that might be at play and be able to minimize or remove that altogether. Thus, each of the two Systems judgement represents two different patterns of thinking: rapid, more variable and more error prone outcomes vs. slow, stable and less error prone outcomes.

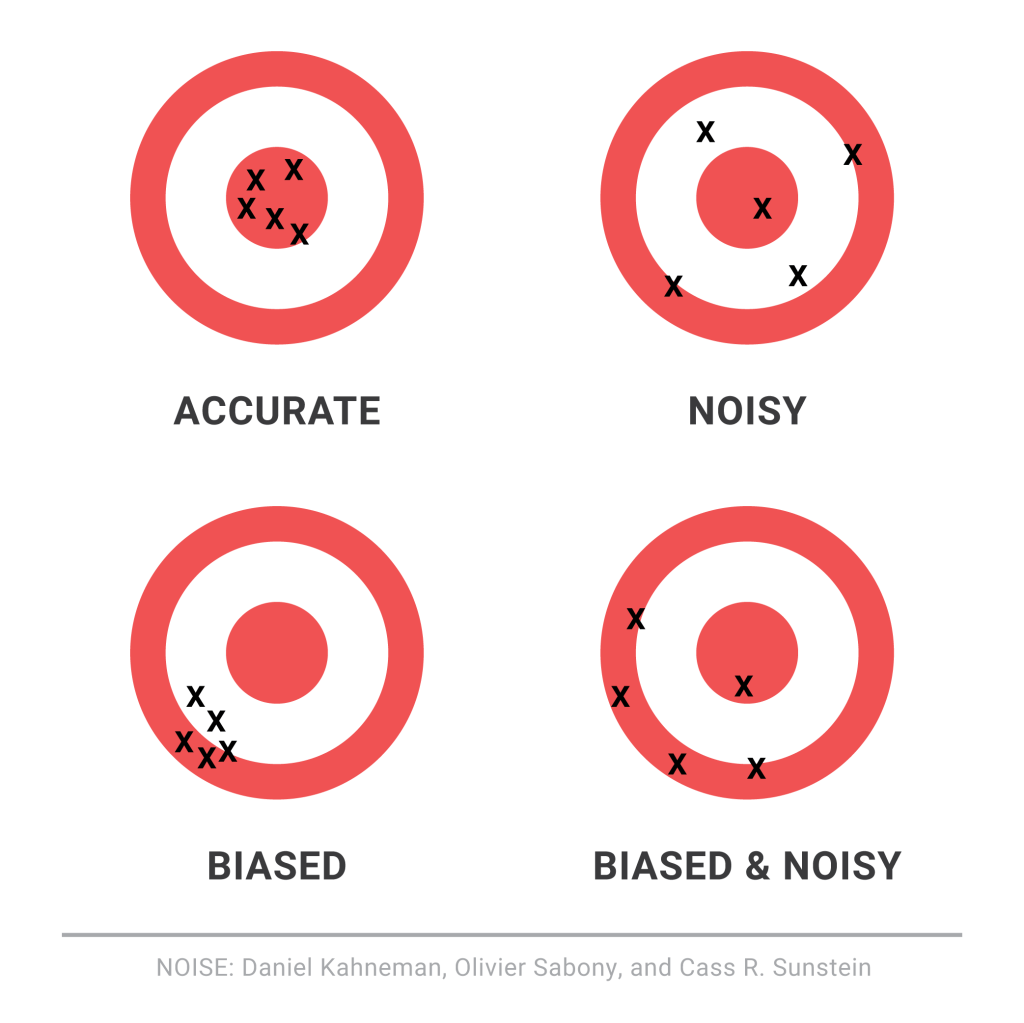

So let us revisit the Bias vs. Variance tradeoff. The idea is that the more bias you bring to address a problem, there is less variance in the aggregate. That does not mean that you are accurate. It only means that there is less variance in the set of outcomes, even if all of the outcomes are materially wrong. But it limits the variance since the bias enforces a constraint in the hypotheses space leading to a smaller and closely knit set of probabilistic outcomes. If you were to remove the constraints in the hypotheses space – namely, you remove bias in the decision framework – well, you are faced with a significant number of possibilities that would result in a larger spread of outcomes. With that said, the expected value of those outcomes might actually be closer to reality, despite the variance – than a framework decided upon by applying heuristic or operating in a bias mode.

So how do we decide then? Jeff Bezos had mentioned something that I recall: some decisions are one-way street and some are two-way. In other words, there are some decisions that cannot be undone, for good or for bad. It is a wise man who is able to anticipate that early on to decide what system one needs to pursue. An organization makes a few big and important decisions, and a lot of small decisions. Identify the big ones and spend oodles of time and encourage a diverse set of input to work through those decisions at a sufficiently high level of detail. When I personally craft rolling operating models, it serves a strategic purpose that might sit on shifting sands. That is perfectly okay! But it is critical to evaluate those big decisions since the crux of the effectiveness of the strategy and its concomitant quantitative representation rests upon those big decisions. Cutting corners can lead to disaster or an unforgiving result!

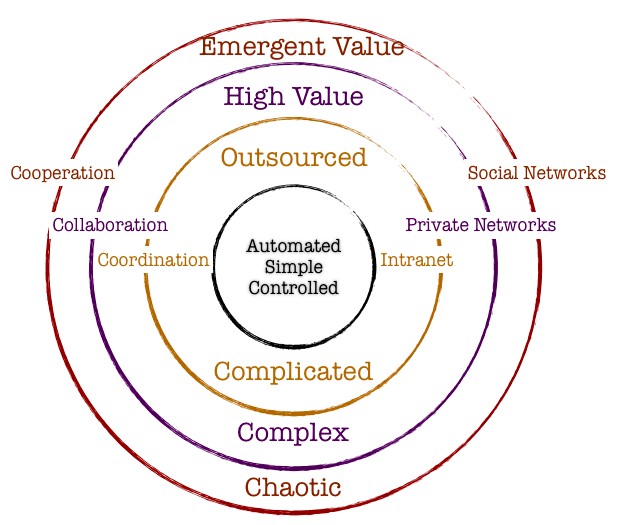

I will focus on the big whale decisions now. I will assume, for the sake of expediency, that the series of small decisions, in the aggregate or by itself, will not sufficiently be large enough that it would take us over the precipice. (It is also important however to examine the possibility that a series of small decisions can lead to a more holistic unintended emergent outcome that might have a whale effect: we come across that in complexity theory that I have already touched on in a set of previous articles).

Cognitive Biases are the biggest mea culpas that one needs to worry about. Some of the more common biases are confirmation bias, attribution bias, the halo effect, the rule of anchoring, the framing of the problem, and status quo bias. There are other cognition biases at play, but the ones listed above are common in planning and execution. It is imperative that these biases be forcibly peeled off while formulating a strategy toward problem solving.

But then there are also the statistical biases that one needs to be wary of. How we select data or selection bias plays a big role in validating information. In fact, if there are underlying statistical biases, the validity of the information is questionable. Then there are other strains of statistical biases: the forecast bias which is the natural tendency to be overtly optimistic or pessimistic without any substantive evidence to support one or the other case. Sometimes how the information is presented: visually or in tabular format – can lead to sins of the error of omission and commission leading the organization and judgement down paths that are unwarranted and just plain wrong. Thus, it is important to be aware of how statistical biases come into play to sabotage your decision framework.

One of the finest illustrations of misjudgment has been laid out by Charlie Munger. Here is the excerpt link : https://fs.blog/great-talks/psychology-human-misjudgment/ He lays out a very comprehensive 25 Biases that ail decision making. Once again, stripping biases do not necessarily result in accuracy — it increases the variability of outcomes that might be clustered around a mean that might be closer to accuracy than otherwise.

Variability is Noise. We do not know a priori what the expected mean is. We are close, but not quite. There is noise or a whole set of outcomes around the mean. Viewing things closer to the ground versus higher would still create a likelihood of accepting a false hypothesis or rejecting a true one. Noise is extremely hard to sift through, but how you can sift through the noise to arrive at those signals that are determining factors, is critical to organization success. To get to this territory, we have eliminated the cognitive and statistical biases. Now is the search for the signal. What do we do then? An increase in noise impairs accuracy. To improve accuracy, you either reduce noise or figure out those indicators that signal an accurate measure.

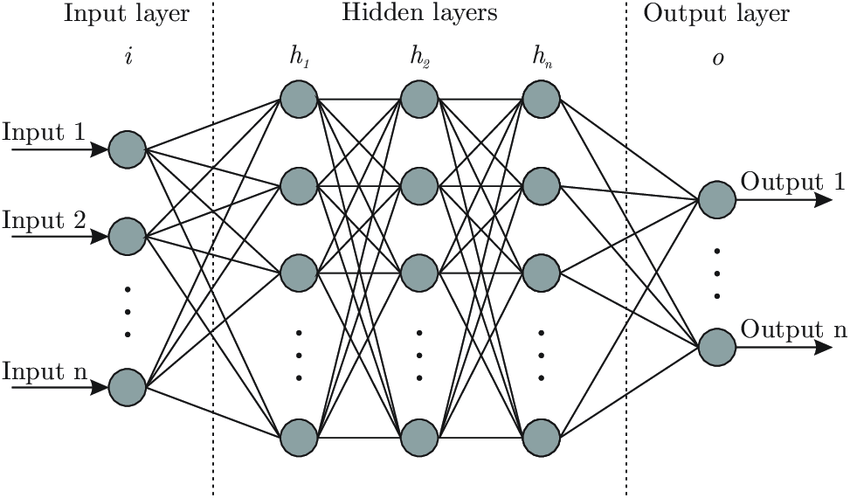

This is where algorithmic thinking comes into play. You start establishing well tested algorithms in specific use cases and cross-validate that across a large set of experiments or scenarios. It has been proved that algorithmic tools are, in the aggregate, superior to human judgement – since it systematically can surface causal and correlative relationships. Furthermore, special tools like principal component analysis and factory analysis can incorporate a large input variable set and establish the patterns that would be impregnable for even System 2 mindset to comprehend. This will bring decision making toward the signal variants and thus fortify decision making.

The final element is to assess the time commitment required to go through all the stages. Given infinite time and resources, there is always a high likelihood of arriving at those signals that are material for sound decision making. Alas, the reality of life does not play well to that assumption! Time and resources are constraints … so one must make do with sub-optimal decision making and establish a cutoff point wherein the benefits outweigh the risks of looking for another alternative. That comes down to the realm of judgements. While George Stigler, a Nobel Laureate in Economics, introduce search optimization in fixed sequential search – a more concrete example has been illustrated in “Algorithms to Live By” by Christian & Griffiths. They suggested an holy grail response: 37% is the accurate answer. In other words, you would reach a suboptimal decision by ensuring that you have explored up to 37% of your estimated maximum effort. While the estimated maximum effort is quite ambiguous and afflicted with all of the elements of bias (cognitive and statistical), the best thinking is to be as honest as possible to assess that effort and then draw your search threshold cutoff.

An important element of leadership is about making calls. Good calls, not necessarily the best calls! Calls weighing all possible circumstances that one can, being aware of the biases, bringing in a diverse set of knowledge and opinions, falling back upon agnostic tools in statistics, and knowing when it is appropriate to have learnt enough to pull the trigger. And it is important to cascade the principles of decision making and the underlying complexity into and across the organization.

Building a Lean Financial Infrastructure!

A lean financial infrastructure presumes the ability of every element in the value chain to preserve and generate cash flow. That is the fundamental essence of the lean infrastructure that I espouse. So what are the key elements that constitute a lean financial infrastructure?

And given the elements, what are the key tweaks that one must continually make to ensure that the infrastructure does not fall into entropy and the gains that are made fall flat or decay over time. Identification of the blocks and monitoring and making rapid changes go hand in hand.

The Key Elements or the building blocks of a lean finance organization are as follows:

- Chart of Accounts: This is the critical unit that defines the starting point of the organization. It relays and groups all of the key economic activities of the organization into a larger body of elements like revenue, expenses, assets, liabilities and equity. Granularity of these activities might lead to a fairly extensive chart of account and require more work to manage and monitor these accounts, thus requiring incrementally a larger investment in terms of time and effort. However, the benefits of granularity far exceeds the costs because it forces management to look at every element of the business.

- The Operational Budget: Every year, organizations formulate the operational budget. That is generally a bottoms up rollup at a granular level that would map to the Chart of Accounts. It might follow a top-down directive around what the organization wants to land with respect to income, expense, balance sheet ratios, et al. Hence, there is almost always a process of iteration in this step to finally arrive and lock down the Budget. Be mindful though that there are feeders into the budget that might relate to customers, sales, operational metrics targets, etc. which are part of building a robust operational budget.

- The Deep Dive into Variances: As you progress through the year and part of the monthly closing process, one would inquire about how the actual performance is tracking against the budget. Since the budget has been done at a granular level and mapped exactly to the Chart of Accounts, it thus becomes easier to understand and delve into the variances. Be mindful that every element of the Chart of Account must be evaluated. The general inclination is to focus on the large items or large variances, while skipping the small expenses and smaller variances. That method, while efficient, might not be effective in the long run to build a lean finance organization. The rule, in my opinion, is that every account has to be looked and the question should be – Why? If the management has agreed on a number in the budget, then why are the actuals trending differently. Could it have been the budget and that we missed something critical in that process? Or has there been a change in the underlying economics of the business or a change in activities that might be leading to these “unexpected variances”. One has to take a scalpel to both – favorable and unfavorable variances since one can learn a lot about the underlying drivers. It might lead to managerially doing more of the better and less of the worse. Furthermore, this is also a great way to monitor leaks in the organization. Leaks are instances of cash that are dropping out of the system. Much of little leaks amounts to a lot of cash in total, in some instances. So do not disregard the leaks. Not only will that preserve the cash but once you understand the leaks better, the organization will step up in efficiency and effectiveness with respect to cash preservation and delivery of value.

- Tweak the process: You will find that as you deep dive into the variances, you might want to tweak certain processes so these variances are minimized. This would generally be true for adverse variances against the budget. Seek to understand why the variance, and then understand all of the processes that occur in the background to generate activity in the account. Once you fully understand the process, then it is a matter of tweaking this to marginally or structurally change some key areas that might favorable resonate across the financials in the future.

- The Technology Play: Finally, evaluate the possibilities of exploring technology to surface issues early, automate repetitive processes, trigger alerts early on to mitigate any issues later, and provide on-demand analytics. Use technology to relieve time and assist and enable more thinking around how to improve the internal handoffs to further economic value in the organization.

All of the above relate to managing the finance and accounting organization well within its own domain. However, there is a bigger step that comes into play once one has established the blocks and that relates to corporate strategy and linking it to the continual evolution of the financial infrastructure.

The essential question that the lean finance organization has to answer is – What can the organization do so that we address every element that preserves and enhances value to the customer, and how do we eliminate all non-value added activities? This is largely a process question but it forces one to understand the key processes and identify what percentage of each process is value added to the customer vs. non-value added. This can be represented by time or cost dimension. The goal is to yield as much value added activities as possible since the underlying presumption of such activity will lead to preservation of cash and also increase cash acquisition activities from the customer.