Blog Archives

Precision at Scale: How to Grow Without Drowning in Complexity

In business, as in life, scale is seductive. It promises more of the good things—revenue, reach, relevance. But it also invites something less welcome: complexity. And the thing about complexity is that it doesn’t ask for permission before showing up. It simply arrives, unannounced, and tends to stay longer than you’d like.

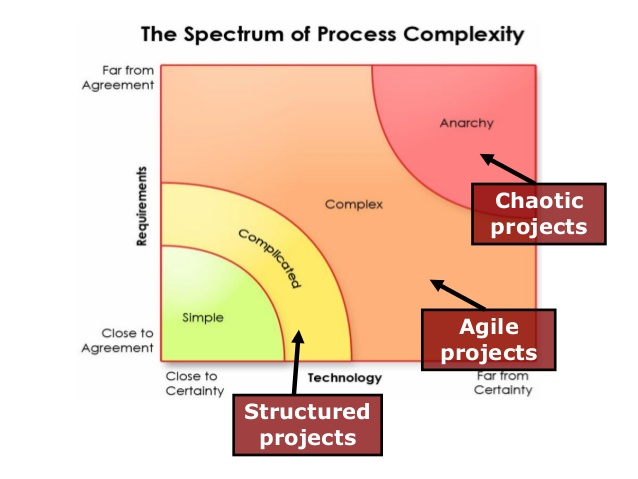

As we pursue scale, whether by growing teams, expanding into new markets, or launching adjacent product lines, we must ask a question that seems deceptively simple: how do we know we’re scaling the right way? That question is not just philosophical—it’s deeply economic. The right kind of scale brings leverage. The wrong kind brings entropy.

Now, if I’ve learned anything from years of allocating capital, it is this: returns come not just from growth, but from managing the cost and coordination required to sustain that growth. In fact, the most successful enterprises I’ve seen are not the ones that scaled fastest. They’re the ones that scaled precisely. So, let’s get into how one can scale thoughtfully, without overinvesting in capacity, and how to tell when the system you’ve built is either flourishing or faltering.

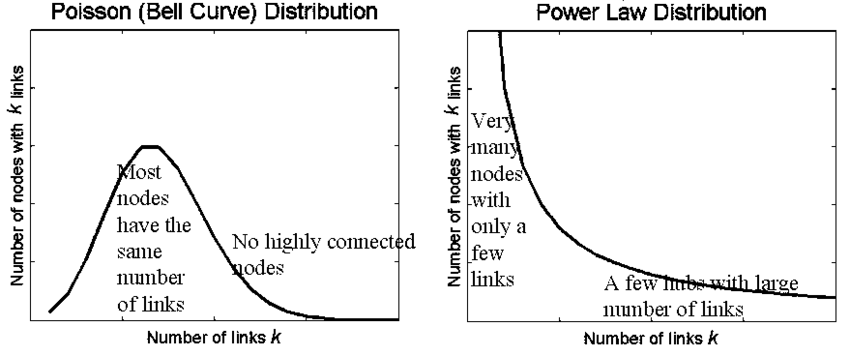

To begin, one must understand that scale and complexity do not rise in parallel; complexity has a nasty habit of accelerating. A company with two teams might have a handful of communication lines. Add a third team, and you don’t just add more conversations—you add relationships between every new and existing piece. In engineering terms, it’s a combinatorial explosion. In business terms, it’s meetings, misalignment, and missed expectations.

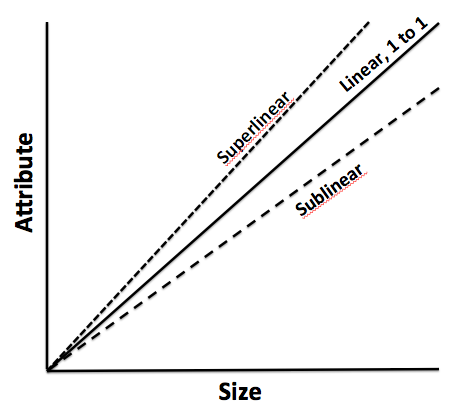

Cities provide a useful analogy. When they grow in population, certain efficiencies appear. Infrastructure per person often decreases, creating cost advantages. But cities also face nonlinear rises in crime, traffic, and disease—all manifestations of unmanaged complexity. The same is true in organizations. The system pays a tax for every additional node, whether that’s a service, a process, or a person. That tax is complexity, and it compounds.

Knowing this, we must invest in capacity like we would invest in capital markets—with restraint and foresight. Most failures in capacity planning stem from either a lack of preparation or an excess of confidence. The goal is to invest not when systems are already breaking, but just before the cracks form. And crucially, to invest no more than necessary to avoid those cracks.

Now, how do we avoid overshooting? I’ve found that the best approach is to treat capacity like runway. You want enough of it to support takeoff, but not so much that you’ve spent your fuel on unused pavement. We achieve this by investing in increments, triggered by observable thresholds. These thresholds should be quantitative and predictive—not merely anecdotal. If your servers are running at 85 percent utilization across sustained peak windows, that might justify additional infrastructure. If your engineering lead time starts rising despite team growth, it suggests friction has entered the system. Either way, what you’re watching for is not growth alone, but whether the system continues to behave elegantly under that growth.

Elegance matters. Systems that age well are modular, not monolithic. In software, this might mean microservices that scale independently. In operations, it might mean regional pods that carry their own load, instead of relying on a centralized command. Modular systems permit what I call “selective scaling”—adding capacity where needed, without inflating everything else. It’s like building a house where you can add another bedroom without having to reinforce the foundation. That kind of flexibility is worth gold.

Of course, any good decision needs a reliable forecast behind it. But forecasting is not about nailing the future to a decimal point. It is about bounding uncertainty. When evaluating whether to scale, I prefer forecasts that offer a range—base, best, and worst-case scenarios—and then tie investment decisions to the 75th percentile of demand. This ensures you’re covering plausible upside without betting on the moon.

Let’s not forget, however, that systems are only as good as the signals they emit. I’m wary of organizations that rely solely on lagging indicators like revenue or margin. These are important, but they are often the last to move. Leading indicators—cycle time, error rates, customer friction, engineer throughput—tell you much sooner whether your system is straining. In fact, I would argue that latency, broadly defined, is one of the clearest signs of stress. Latency in delivery. Latency in decisions. Latency in feedback. These are the early whispers before systems start to crack.

To measure whether we’re making good decisions, we need to ask not just if outcomes are improving, but if the effort to achieve them is becoming more predictable. Systems with high variability are harder to scale because they demand constant oversight. That’s a recipe for executive burnout and organizational drift. On the other hand, systems that produce consistent results with declining variance signal that the business is not just growing—it’s maturing.

Still, even the best forecasts and the finest metrics won’t help if you lack the discipline to say no. I’ve often told my teams that the most underrated skill in growth is the ability to stop. Stopping doesn’t mean failure; it means the wisdom to avoid doubling down when the signals aren’t there. This is where board oversight matters. Just as we wouldn’t pour more capital into an underperforming asset without a turn-around plan, we shouldn’t scale systems that aren’t showing clear returns.

So when do we stop? There are a few flags I look for. The first is what I call capacity waste—resources allocated but underused, like a datacenter running at 20 percent utilization, or a support team waiting for tickets that never come. That’s not readiness. That’s idle cost. The second flag is declining quality. If error rates, customer complaints, or rework spike following a scale-up, then your complexity is outpacing your coordination. Third, I pay attention to cognitive load. When decision-making becomes a game of email chains and meeting marathons, it’s time to question whether you’ve created a machine that’s too complicated to steer.

There’s also the budget creep test. If your capacity spending increases by more than 10 percent quarter over quarter without corresponding growth in throughput, you’re not scaling—you’re inflating. And in inflation, as in business, value gets diluted.

One way to guard against this is by treating architectural reserves like financial ones. You wouldn’t deploy your full cash reserve just because an opportunity looks interesting. You’d wait for evidence. Similarly, system buffers should be sized relative to forecast volatility, not organizational ambition. A modest buffer is prudent. An oversized one is expensive insurance.

Some companies fall into the trap of building for the market they hope to serve, not the one they actually have. They build as if the future were guaranteed. But the future rarely offers such certainty. A better strategy is to let the market pull capacity from you. When customers stretch your systems, then you invest. Not because it’s a bet, but because it’s a reaction to real demand.

There’s a final point worth making here. Scaling decisions are not one-time events. They are sequences of bets, each informed by updated evidence. You must remain agile enough to revise the plan. Quarterly evaluations, architectural reviews, and scenario testing are the boardroom equivalent of course correction. Just as pilots adjust mid-flight, companies must recalibrate as assumptions evolve.

To bring this down to earth, let me share a brief story. A fintech platform I advised once found itself growing at 80 percent quarter over quarter. Flush with success, they expanded their server infrastructure by 200 percent in a single quarter. For a while, it worked. But then something odd happened. Performance didn’t improve. Latency rose. Error rates jumped. Why? Because they hadn’t scaled the right parts. The orchestration layer, not the compute layer, was the bottleneck. Their added capacity actually increased system complexity without solving the real issue. It took a re-architecture, and six months of disciplined rework, to get things back on track. The lesson: scaling the wrong node is worse than not scaling at all.

In conclusion, scale is not the enemy. But ungoverned scale is. The real challenge is not growth, but precision. Knowing when to add, where to reinforce, and—perhaps most crucially—when to stop. If we build systems with care, monitor them with discipline, and remain intellectually honest about what’s working, we give ourselves the best chance to grow not just bigger, but better.

And that, to borrow a phrase from capital markets, is how you compound wisely.

Internal versus External Scale

This article discusses internal and external complexity before we tee up a more detailed discussion on internal versus external scale. This chapter acknowledges that complex adaptive systems have inherent internal and external complexities which are not additive. The impact of these complexities is exponential. Hence, we have to sift through our understanding and perhaps even review the salient aspects of complexity science which have already been covered in relatively more detail in earlier chapter. However, revisiting complexity science is important, and we will often revisit this across other blog posts to really hit home the fundamental concepts and its practical implications as it relates to management and solving challenges at a business or even a grander social scale.

A complex system is a part of a larger environment. It is a safe to say that the larger environment is more complex than the system itself. But for the complex system to work, it needs to depend upon a certain level of predictability and regularity between the impact of initial state and the events associated with it or the interaction of the variables in the system itself. Note that I am covering both – complex physical systems and complex adaptive systems in this discussion. A system within an environment has an important attribute: it serves as a receptor to signals of external variables of the environment that impact the system. The system will either process that signal or discard the signal which is largely based on what the system is trying to achieve. We will dedicate an entire article on system engineering and thinking later, but the uber point is that a system exists to serve a definite purpose. All systems are dependent on resources and exhibits a certain capacity to process information. Hence, a system will try to extract as many regularities as possible to enable a predictable dynamic in an efficient manner to fulfill its higher-level purpose.

Let us understand external complexities. We can interchangeably use the word environmental complexity as well. External complexity represents physical, cultural, social, and technological elements that are intertwined. These environments beleaguered with its own grades of complexity acts as a mold to affect operating systems that are mere artifacts. If operating systems can fit well within the mold, then there is a measure of fitness or harmony that arises between an internal complexity and external complexity. This is the root of dynamic adaptation. When external environments are very complex, that means that there are a lot of variables at play and thus, an internal system has to process more information in order to survive. So how the internal system will react to external systems is important and they key bridge between those two systems is in learning. Does the system learn and improve outcomes on account of continuous learning and does it continually modify its existing form and functional objectives as it learns from external complexity? How is the feedback loop monitored and managed when one deals with internal and external complexities? The environment generates random problems and challenges and the internal system has to accept or discard these problems and then establish a process to distribute the problems among its agents to efficiently solve those problems that it hopes to solve for. There is always a mechanism at work which tries to align the internal complexity with external complexity since it is widely believed that the ability to efficiently align the systems is the key to maintaining a relatively competitive edge or intentionally making progress in solving a set of important challenges.

Internal complexity are sub-elements that interact and are constituents of a system that resides within the larger context of an external complex system or the environment. Internal complexity arises based on the number of variables in the system, the hierarchical complexity of the variables, the internal capabilities of information pass-through between the levels and the variables, and finally how it learns from the external environment. There are five dimensions of complexity: interdependence, diversity of system elements, unpredictability and ambiguity, the rate of dynamic mobility and adaptability, and the capability of the agents to process information and their individual channel capacities.

If we are discussing scale management, we need to ask a fundamental question. What is scale in the context of complex systems? Why do we manage for scale? How does management for scale advance us toward a meaningful outcome? How does scale compute in internal and external complex systems? What do we expect to see if we have managed for scale well? What does the future bode for us if we assume that we have optimized for scale and that is the key objective function that we have to pursue?