Category Archives: finance

How Strategic CFOs Drive Sustainable Growth and Change

When people ask me what the most critical relationship in a company really is, I always say it’s the one between the CEO and the CFO. And no, I am not being flippant. In my thirty years helping companies manage growth, navigate crises, and execute strategic shifts, the moments that most often determine success or spiraled failure often rests on how tightly the CEO and CFO operate together. One sets a vision. The other turns aspiration into action. Alone, each has influence; together, they can transform the business.

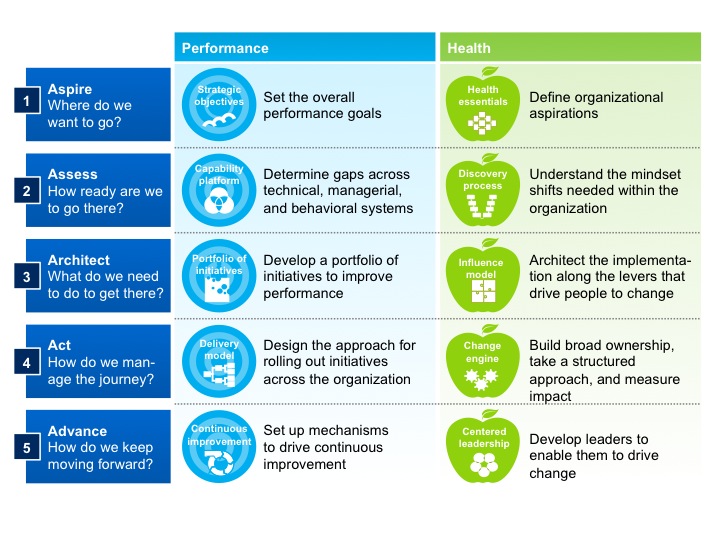

Transformation, after all, is not a project. It is a culture shift, a strategic pivot, a redefinition of operating behaviors. It’s more art than engineering and more people than process. And at the heart of it lies a fundamental tension: You need ambition, yet you must manage risk. You need speed, but you cannot abandon discipline. You must pursue new business models while preserving your legacy foundations. In short, you need to build simultaneously on forward momentum and backward certainty.

That complexity is where the strategic CFO becomes indispensable. The CFO’s job is not just to count beans, it’s to clear the ground where new plants can grow. To unlock capital without unleashing chaos. To balance accountable rigor with growth ambition. To design transformation from the numbers up, not just hammer it into the planning cycle. When this role is fulfilled, the CEO finds their most trusted confidante, collaborator, and catalyst.

Think of it this way. A CEO paints a vision: We must double revenue, globalize our go-to-market, pivot into new verticals, revamp the product, or embrace digital. It sounds exciting. It feels bold. But without a financial foundation, it becomes delusional. Does the company have the cash runway? Can the old cost base support the new trajectory? Are incentives aligned? Are the systems ready? Will the board nod or push back? Who is accountable if sales forecast misses or an integration falters? A CFO’s strategic role is to bring those questions forward not cynically, but constructively—so the ambition becomes executable.

The best CEOs I’ve worked with know this partnership instinctively. They build strategy as much with the CFO as with the head of product or sales. They reward honest challenge, not blind consensus. They request dashboards that update daily, not glossy decks that live in PowerPoint. They ask, “What happens to operating income if adoption slows? Can we reverse full-time hiring if needed? Which assumptions unlock upside with minimal downside?” Then they listen. And change. That’s how transformation becomes durable.

Let me share a story. A leader I admire embarked on a bold plan: triple revenue in two years through international expansion and a new channel model. The exec team loved the ambition. Investors cheered. But the CFO, without hesitation, did not say no. She said let us break it down. Suppose it costs $30 million to build international operations, $12 million to fund channel enablement, plus incremental headcount, marketing expenses, R&D coordination, and overhead. Let us stress test the plan. What if licensing stalls? What if fulfillment issues delay launches? What if cross-border tax burdens permanently drag down the margin?

The CEO wanted the bold headline number. But together, they translated it into executable modules. They set up rolling gates: a $5 million pilot, learn, fund next $10 million, learn, and so on. They built exit clauses. They aligned incentives so teams could pivot without losing credibility. They also built redundancy into systems and analytics, with daily data and optionality-based budgeting. The CEO had the vision, but the CFO gave it a frame. That is partnership.

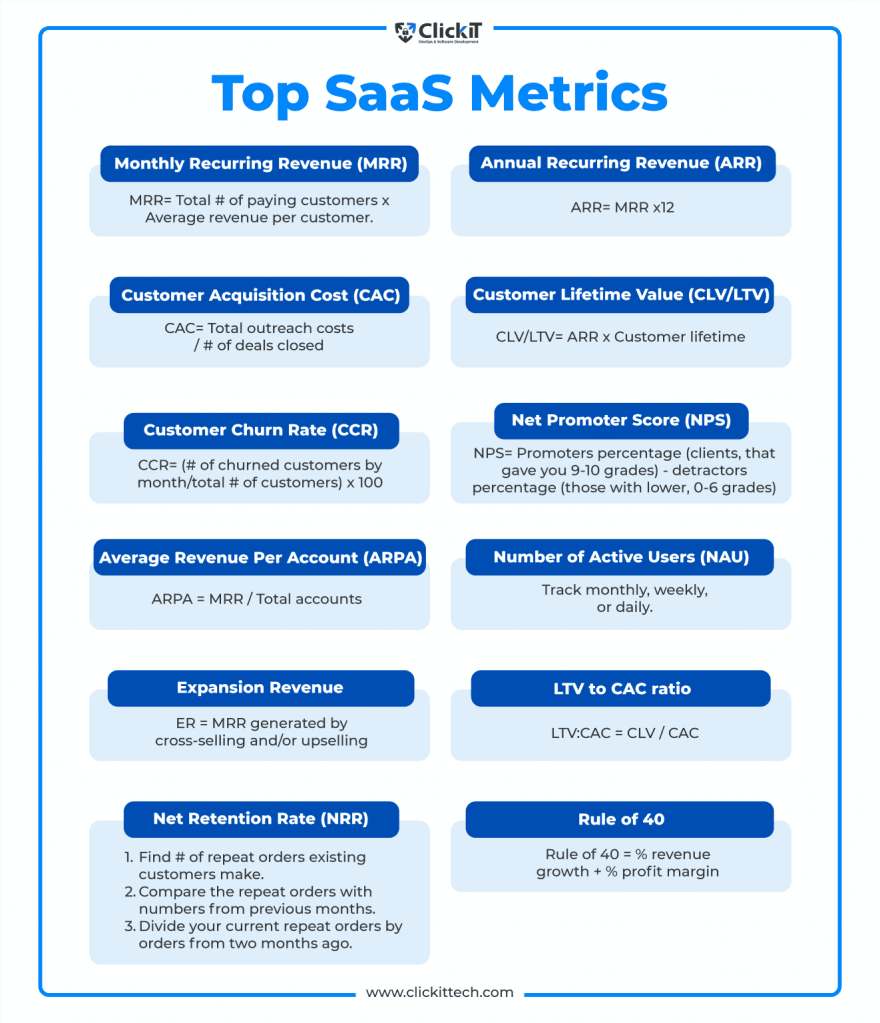

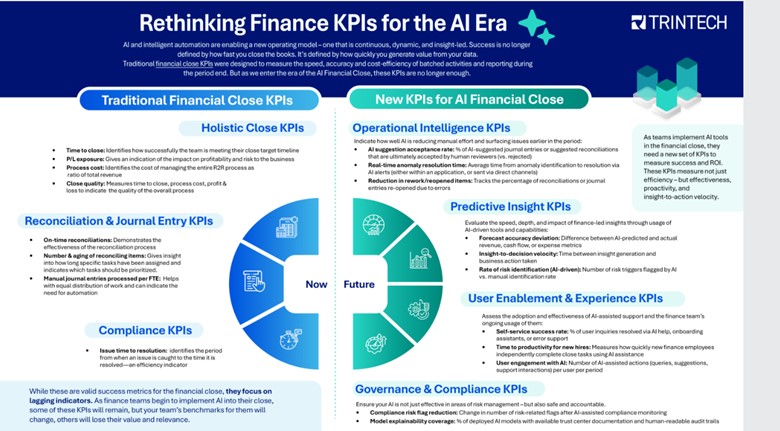

That framing role extends beyond capital structure or P&L. It bleeds into operating rhythm. The strategic CFO becomes the architect of transformation cadence. They design how weekly, monthly, and quarterly look and feel. They align incentive schemes so that geography may outperform globally while still holding central teams accountable. They align finance, people, product, and GTM teams to shared performance metrics—not top-level vanity metrics, but actionable ones: user engagement, cost per new customer, onboarding latency, support burden, renewal velocity. They ensure data is not stashed in silos. They make it usable, trusted, visible. Because transformation is only as effective as your ability to measure missteps, iterate, and learn.

This is why I say the CFO becomes a strategic weapon: a lever for insight, integration, and investment.

Boards understand this too, especially when it is too late. They see CEOs who talk of digital transformation while still approving global headcount hikes. They see operating legacy systems still dragging FY ‘Digital 2.0’ ambition. They see growth funded, but debt rising with little structural benefit. In those moments, they turn to the CFO. The board does not ask the CFO if they can deliver the numbers. They ask whether the CEO can. They ask, “What’s the downside exposure? What are the guardrails? Who is accountable? How long will transformation slow profitability? And can we reverse if needed?”

That board confidence, when positive, is not accidental. It comes from a CFO who built that trust, not by polishing a spreadsheet, but by building strategy together, testing assumptions early, and designing transformation as a financial system.

Indeed, transformation without control is just creative destruction. And while disruption may be trendy, few businesses survive without solid footing. The CFO ensures that disruption does not become destruction. That investments scale with impact. That flexibility is funded. That culture is not ignored. That when exceptions arise, they do not unravel behaviors, but refocus teams.

This is often unseen. Because finance is a support function, not a front-facing one. But consider this: it is finance that approves the first contract. Finance assists in setting the commission structure that defines behavior. Finance sets the credit policy, capital constraints, and invoice timing, and all of these have strategic logic. A CFO who treats each as a tactical lever becomes the heart of transformation.

Take forecasting. Transformation cannot run on backward-moving averages. Yet too many companies rely on year-over-year rates, lagged signals, and static targets. The strategic CFO resurrects forecasting. They bring forward leading indicators of product usage, sales pipeline, supply chain velocity. They reframe forecasts as living systems. We see a dip? We call a pivot meeting. We see high churn? We call the product team. We see hiring cost creep? We call HR. Forewarned is forearmed. That is transformation in flight.

On the capital front, the CFO becomes a barbell strategist. They pair patient growth funding with disciplined structure. They build in fields of optionality: reserves for opportunistic moves, caps on unfunded headcount, staged deployment, and scalable contracts. They calibrate pricing experiments. They design customer acquisition levers with off ramps. They ensure that at every step of change, you can set a gear to reverse—without losing momentum, but with discipline.

And they align people. Transformation hinges on mindset. In fast-moving companies, people often move faster than they think. Great leaders know this. The strategic CFO builds transparency into compensation. They design equity vesting tied to transformation metrics. They design long-term incentives around cross-functional execution. They also design local authority within discipline. Give leaders autonomy, but align them to the rhythm of finance. Even the best strategy dies when every decision is a global approval. Optionality must scale with coordination.

Risk management transforms too. In the past, the CFO’s role in transformation was to shield operations from political turbulence. Today, it is to internally amplify controlled disruption. That means modeling volatility with confidence. Scenario modeling under market shock, regulatory shift, customer segmentation drift. Not just building firewalls, but designing escape ramps and counterweights. A transformation CFO builds risk into transformation—but as a system constraint to be managed, not a gate to prevent ambition.

I once had a CEO tell me they felt alone when delivering digital transformation. HR was not aligned. Product was moving too slowly. Sales was pushing legacy business harder. The CFO had built a bridge. They brought HR, legal, sales, and marketing into weekly update sessions, each with agreed metrics. They brokered resolutions. They surfaced trade-offs confidently. They pressed accountability floor—not blame, but clarity. That is partnership. That is transformation armor.

Transformation also triggers cultural tectonics. And every tectonic shift features friction zones—power renegotiation, process realignment, work redesign. Without financial discipline, politics wins. Mistrust builds. Change derails. The strategic CFO intervenes not as a policeman, but as an arbiter of fairness: If people are asked to stretch, show them the ROI. If processes migrate, show them the rationale. If roles shift, unpack the logic. Maintaining trust alignment during transformation is as important as securing funding.

The ability to align culture, capital, cadence, and accountability around a single north star—that is the strategic CFO’s domain.

And there is another hidden benefit: the CFO’s posture sets the tone for transformation maturity. CFOs who co-create, co-own, and co-pivot build transformation muscle. Those companies that learn together scale transformation together.

I once wrote that investors will forgive a miss if the learning loops are obvious. That is also true inside the company. When a CEO and CFO are aligned, and the CFO is the first to acknowledge what is not working to expectations, when pivots are driven by data rather than ego, that establishes the foundation for resilient leadership. That is how companies rebuild trust in growth every quarter. That is how transformation becomes a norm.

If there is a fear inside the CFO community, it is the fear of being visible. A CFO may believe that financial success is best served quietly. But the moment they step confidently into transformation, they change that dynamic. They say: Yes, we own the books. But we also own the roadmap. Yes, we manage the tail risk. But we also amplify the tail opportunity. That mindset is contagious. It builds confidence across the company and among investors. That shift in posture is more valuable than any forecast.

So let me say it again. Strategy is not a plan. Mechanics do not make execution. Systems do. And at the junction of vision and execution, between boardroom and frontline, stands the CFO. When transformation is on the table, the CFO walks that table from end to end. They make sure the chairs are aligned. The evidence is available. The accountability is shared. The capital is allocated, measured, and adapted.

This is why I refer to the CFO as the CEO’s most important ally. Not simply a confidante. Not just a number-cruncher. A partner in purpose. A designer of execution. A steward of transformation. Which is why, if you are a CFO reading this, I encourage you: step forward. You do not need permission to rethink transformation. You need conviction to shape it. And if you can build clarity around capital, establish a cadence for metrics, align incentives, and implement systems for governance, you will make your CEO’s job easier. You will elevate your entire company. You will unlock optionality not just for tomorrow, but for the years that follow. Because in the end, true transformation is not a moment. It is a movement. And the CFO, when prepared, can lead it.

The CFO’s Role in Cyber Risk Management

The modern finance function, once built on ledgers and guarded by policy, now lives almost entirely in code. Spreadsheets have become databases, vaults have become clouds, and the most sensitive truths of a corporation, like earnings, projections, controls, and compensation, exist less in file cabinets and more in digital atmospheres. With that transformation has come both immense power and a new kind of vulnerability. Finance, once secure in the idea that security was someone else’s concern, now finds itself at the frontlines of cyber risk.

This is not an abstraction. It is not the theoretical fear that lives in PowerPoint decks and tabletop exercises. It is the quiet, urgent reality that lives in every system login, every vendor integration, every data feed, and control point. Finance holds the keys to liquidity, to payroll, to treasury pipelines, to the very structure of internal trust. When cyber risk is real, it is financial risk. And when controls are breached, the numbers are not the only thing that shatter. You lose confidence, and the reputational risk is sticky.

The vocabulary of cybersecurity has long been technical, coded in the language of firewalls, encryption, threat surfaces, and zero-day exploits. But finance speaks a different dialect. We talk of exposure, continuity, auditability, and control. The true challenge is not simply to secure the digital perimeter. It is to translate cybersecurity into terms of governance, capital stewardship, and business continuity. This is the work of resilience. Not just defending the system, but ensuring the system can recover, restore, and preserve value under duress.

At the core of this transformation lies data governance. The finance function is very data-intensive. Forecasting, compliance, scenario modeling, and shareholder reporting all rely on the integrity of structured data. Yet in many organizations, data governance is fragmented. Spreadsheets circulate beyond their owners. Sensitive assumptions are stored in personal folders. Access rights sprawl. The very fuel of modern finance—real-time, interconnected, multi-source data—becomes a liability when it is ungoverned.

Good governance begins with clarity: what data exists, who owns it, who touches it, and where it flows. Finance must work hand-in-glove with IT to establish data taxonomies, define master records, enforce role-based access, and ensure encryption in transit and at rest. This is not busywork. It is the scaffolding of cyber hygiene. Without it, even the most advanced cybersecurity investments like AI-driven threat detection, intrusion response, and behavioral analytics will fail to protect what cannot be clearly seen or structurally controlled.

But governance is only the beginning. The real test lies in continuity. Cyber risk does not always appear as a breach. Sometimes, it appears as latency. A payroll file that fails to transmit. A trading system that goes dark. A treasury platform was locked by ransomware. I know some banks that were hit by bad actors. The damage is not theoretical. It is operational. Financial leaders must therefore shift their attention from perimeter defense to resilience engineering, which essentially means designing systems that are fault-tolerant, recoverable, and auditable even under cyber stress.

This involves more than backup protocols or redundant servers. It requires scenario thinking. What happens if our accounts payable system is locked for 48 hours? What if our cloud provider is compromised? What if our vendors become attack vectors? Resilience means designing finance systems with degraded modes—ensuring that key processes like payroll, fund transfer, and regulatory filing can continue, even if other systems are compromised.

Cyber risk also brings a strategic lens to third-party exposure. In an increasingly connected ecosystem—outsourced payroll, cloud ERPs, digital banks, fintech APIs—finance’s risk perimeter is now shared with others. Vendor due diligence, once a procurement checkbox, must now include cybersecurity audits, penetration tests, and shared incident response plans. The risk is no longer only what happens inside your house, but what happens next door.

As this landscape evolves, the CFO must take a more active seat at the cybersecurity table. This is not just a matter of policy; it is a matter of posture. Cybersecurity is not solely an IT concern. It is a financial one. It affects liquidity planning, insurance coverage, regulatory exposure, and reputational capital. It demands board-level attention and enterprise-level investment. And it benefits enormously from the disciplines finance brings to bear: control frameworks, risk quantification, scenario planning, and governance structures.

The future of managing cyber risk in finance lies in integration. Not in building walls, but in building bridges—between IT and FP&A, between security protocols and business rules, between resilience architecture and capital planning. Finance professionals do not need to become technologists. But they must become interpreters—able to translate digital risk into economic consequence, and to shape investment decisions accordingly.

In recent years, regulators have taken note. New reporting requirements around cyber incidents, from the SEC to international financial authorities, are forcing companies to formalize what was once left informal. Boards are asking tougher questions. Insurance markets are pricing risk more carefully. And investors are beginning to distinguish between companies that prepare and those that hope.

All of these points point to a subtle but important shift: cybersecurity is no longer about threat prevention. It is about enterprise trust. It is about whether a company can maintain its operations, protect its capital, and recover its footing when—not if—an incident occurs. And finance, as the institutional function of trust, is uniquely positioned to lead.

To do so, we must go beyond cost-benefit analyses of security tools. We must think in terms of systemic resilience. What are the controls that matter most? What is our recovery time objective? What are the systems of record we cannot afford to lose? Which processes must remain manual-capable, should automation fail? These are financial design questions. And they demand financial stewardship.

There is an old assumption that the CFO guards the past, while the CIO builds the future. But in the world of cyber risk, that boundary dissolves. Today, the CFO must guard the continuity of the future. And that means thinking like a strategist, acting like a technologist, and investing like a risk manager.

Managing cybersecurity risk in finance is not about responding to the last attack. It is about preparing for the next one—and the one after that. It is about designing systems that are not only efficient in normal times but also defensible in moments of failure. It is about knowing that the numbers we report, the capital we protect, and the trust we uphold, which is that we all depend on systems we can govern, audit, and restore.

Resilience is not a project. It is a philosophy. And in a world where the invisible breach can shape the visible outcome, it may be the most important capital a CFO can build.

Building a Lean Financial Infrastructure!

A lean financial infrastructure presumes the ability of every element in the value chain to preserve and generate cash flow. That is the fundamental essence of the lean infrastructure that I espouse. So what are the key elements that constitute a lean financial infrastructure?

And given the elements, what are the key tweaks that one must continually make to ensure that the infrastructure does not fall into entropy and the gains that are made fall flat or decay over time. Identification of the blocks and monitoring and making rapid changes go hand in hand.

The Key Elements or the building blocks of a lean finance organization are as follows:

- Chart of Accounts: This is the critical unit that defines the starting point of the organization. It relays and groups all of the key economic activities of the organization into a larger body of elements like revenue, expenses, assets, liabilities and equity. Granularity of these activities might lead to a fairly extensive chart of account and require more work to manage and monitor these accounts, thus requiring incrementally a larger investment in terms of time and effort. However, the benefits of granularity far exceeds the costs because it forces management to look at every element of the business.

- The Operational Budget: Every year, organizations formulate the operational budget. That is generally a bottoms up rollup at a granular level that would map to the Chart of Accounts. It might follow a top-down directive around what the organization wants to land with respect to income, expense, balance sheet ratios, et al. Hence, there is almost always a process of iteration in this step to finally arrive and lock down the Budget. Be mindful though that there are feeders into the budget that might relate to customers, sales, operational metrics targets, etc. which are part of building a robust operational budget.

- The Deep Dive into Variances: As you progress through the year and part of the monthly closing process, one would inquire about how the actual performance is tracking against the budget. Since the budget has been done at a granular level and mapped exactly to the Chart of Accounts, it thus becomes easier to understand and delve into the variances. Be mindful that every element of the Chart of Account must be evaluated. The general inclination is to focus on the large items or large variances, while skipping the small expenses and smaller variances. That method, while efficient, might not be effective in the long run to build a lean finance organization. The rule, in my opinion, is that every account has to be looked and the question should be – Why? If the management has agreed on a number in the budget, then why are the actuals trending differently. Could it have been the budget and that we missed something critical in that process? Or has there been a change in the underlying economics of the business or a change in activities that might be leading to these “unexpected variances”. One has to take a scalpel to both – favorable and unfavorable variances since one can learn a lot about the underlying drivers. It might lead to managerially doing more of the better and less of the worse. Furthermore, this is also a great way to monitor leaks in the organization. Leaks are instances of cash that are dropping out of the system. Much of little leaks amounts to a lot of cash in total, in some instances. So do not disregard the leaks. Not only will that preserve the cash but once you understand the leaks better, the organization will step up in efficiency and effectiveness with respect to cash preservation and delivery of value.

- Tweak the process: You will find that as you deep dive into the variances, you might want to tweak certain processes so these variances are minimized. This would generally be true for adverse variances against the budget. Seek to understand why the variance, and then understand all of the processes that occur in the background to generate activity in the account. Once you fully understand the process, then it is a matter of tweaking this to marginally or structurally change some key areas that might favorable resonate across the financials in the future.

- The Technology Play: Finally, evaluate the possibilities of exploring technology to surface issues early, automate repetitive processes, trigger alerts early on to mitigate any issues later, and provide on-demand analytics. Use technology to relieve time and assist and enable more thinking around how to improve the internal handoffs to further economic value in the organization.

All of the above relate to managing the finance and accounting organization well within its own domain. However, there is a bigger step that comes into play once one has established the blocks and that relates to corporate strategy and linking it to the continual evolution of the financial infrastructure.

The essential question that the lean finance organization has to answer is – What can the organization do so that we address every element that preserves and enhances value to the customer, and how do we eliminate all non-value added activities? This is largely a process question but it forces one to understand the key processes and identify what percentage of each process is value added to the customer vs. non-value added. This can be represented by time or cost dimension. The goal is to yield as much value added activities as possible since the underlying presumption of such activity will lead to preservation of cash and also increase cash acquisition activities from the customer.

Debt Financing: Notable Elements to consider

We have discussed financing via Convertible Debts and Equity Financing. There is a third element that is equally important and ought to be in the arsenal for financing the working capital requirements for the company.

Here are some common Term Sheet lexicons that you have to be aware of for opening up a credit facility.

Formula based Line of Credit: There are some variants to this, but the key driver is that the LOC is extended against eligible receivables. Generally, eligible receivables are defined as receivables that are within 90 days at an uber level. There are some additional elements that can reduce the eligible base. Those items that can be excluded would be as follows

Accounts outstanding for more than 90 days from invoice date

Credit balances over 90 days

Foreign AR. Some banks would specifically exclude foreign AR.

Intra-Company AR

Banks might impose a concentration limit. For example, any account that represents more than 30% of the AR that is outstanding may be excluded from the mix. Alternatively, credit may be extended up to the cap of 30% and no more.

Cross Aging Limit of 35%, defined as those accounts where 35% or more of an accounts receivable past due (greater than 90 days). In such instances, the entire account is ineligible.

Pre-bills are not eligible. Services have to be rendered or goods shipped. That constitutes a true invoice.

Some instances, you may be precluded from including receivables from government. Non-Formula based LOC: Credit is extended not on AR but based on what you negotiate with the Bank. The Bank will generally provide a non-formula based LOC based on historical cash flows and EBITDA and a board-approved budget. In some instances, if you feel that you can capitalize the company via an equity line in the near future, the bank would be inclined to raise the LOC.

Interest Rate

In either of the above 2 cases, the interest rate charged is basically a prime reference rate + some basis points. For example, the bank may spell out that the interest rate is the Prime Referenced Rate + 1.25%. If the Prime rate is 3.25%, then the cost to the company is 4.5%. Note though that if the company is profitable and the average tax rate is 40%, then the real cost to the company is 4.5 %*( 1-40%) = 2.7%.

Maturity Period

For all facilities, there is Maturity Period. In most instances, it is 24 months. Interest is paid monthly and the principal is due at maturity.

Facility Fees

Banks will charge a Facility Fee. Depending on the size of the facility, there could be some amount due at close and some amount due at the first year anniversary from the date the facility contract has been executed.

First Priority Rights

Bank will have a first priority UCC-1 security interest on all assets of Borrower like present and future inventory, chattel paper, accounts, contract rights, unencumbered equipment, general intangibles (excluding intellectual property), and the right to proceeds from accounts receivable and inventory from the sale of intellectual property to repay any outstanding Bank debt.

Bank may insist on having the right to the IP. That becomes another negotiation point. You can negotiate a negative pledge which effectively means that you will not pledge your IP to any third party.

Bank Covenants

The Bank will also insist on some financial covenants. Some of the common covenants are

- Adjusted Quick Ratio which is (Cash held at the Bank + Eligible Receivables)/ (Current Liabilities less Deferred Revenue)

- Trailing EBITDA requirement. Could be a six month or 12 month trailing EBITDA requirement

- EBIT to Interest Coverage Ratio = EBIT/Interest Payments. Bank may require a 1.5 or 2 coverage.

Monthly Financial Requirements

Bank will require the monthly financial statements according to GAAP and the Bank Compliance Certificate.

Bank may seek an Audit or an independent review of the Financial Statements within 90-180 days after each fiscal year ends.

You will have to provide AR and AP aging monthly and inventory breakdown.

In the event that there is a reforecast of the Budget or Operating Plan and it has been approved by the Board, you will have to provide the information to the bank as well.

Bank Oversight and Audit

Bank will reserve the right to do a collateral audit for the formula based line of credit financing. You will have to pay the audit fees. In general, you can negotiate and cap these fees and the frequency of such audits.

Most of the above relate to a large number of startups that do not carry inventory and acquire inventory from international suppliers.

Bankers Acceptance

BAs are frequently used in international trade because of advantages for both sides. Exporters often feel safer relying on payment from a reputable bank than a business with which it has little if any history. Once the bank verifies, or “accepts”, a time draft, it becomes a primary obligation of that institution.

Here’s one typical example. You decide to purchase 100 widgets from Lee Ku, a Chinese exporter. After completing the trade agreement, you approach your bank for a letter of credit. This letter of credit makes your bank the intermediary responsible for completing the transaction.

Once Lee Ku, your supplier, ships the goods, it sends the appropriate documents – typically through its own financial bank to your bank in the United States. The exporter now has a couple choices. It could keep the acceptance until maturity, or it could sell it to a third party, perhaps to your bank responsible for making the payment. In this case, Lee Ku receives an amount less than the face value of the draft, but it doesn’t have to wait on the funds. Bank makes some fees and the Supplier gets their money.

When a bank buys back the acceptance at a lower price, it is said to be “discounting” the acceptance. If your bank does this, it essentially has the same choices that your Chinese exporter had. It could hold the draft until it matures, which is akin to extending the importer a loan. More commonly, though, the bank will charge you a fee in advance which is a percentage of the acceptance. Could be anywhere from 2-4% of the value of the acceptance. In theory, you can get anywhere between 90-180 days financing using BA as an instrument to fund your inventory.

Dangers of Debt Financing

Debt Financing can be a cheap financing method. However, it carries potential risk. If you are not able to service debt, then the bank can, at the extreme, force you into bankruptcy. Alternatively, they can put you in forbearance and work out a plan to get back their principal amount. They can take over the role of receivership and collect the money on your behalf. These are all draconian triggers that may happen, and hence it is important to maintain a good relationship with your banker. Most importantly, give them any bad news ahead of time. It is really bad when they learn of bad news later. It would limit your ability to negotiate terms with the bank.

Manage Debt

In general, if you draw down against the LOC, it is always a good idea to pay that down as soon as possible. That ought to be your primary operational strategy. That will minimize interest expense, keep the line open, establish a better rapport with the bank and most importantly – force you to become a more disciplined organization. You ought to regard the bank financing as a bridge for your working capital requirements. To the extent you can minimize the bridge by converting your receivables to cash, minimizing operating expenses, and maximizing your margin … you would be in a happier place. Debt financing also gives you the time to build value in the organization rather than relying upon equity line which is a costly form of financing. Having said that, there will be times when your investors may push back on your debt financing strategy. In fact, if you have raised equity prior to debt, you may even have to get signoff from the equity investors. Their big concern is that having leverage takes away from the value of the company. That is not necessarily true, because corporate finance theory suggests that intelligent debt financing can, in fact, increase corporate value. However, the investors may see debt as your way out to stall more investment requirements and thus defer their inclination toward owning more of your company at a lower value.

Term Sheets: Landmines and Ticking Time Bombs!

Wall Street is the only place that people ride to in a Rolls Royce to get advice from those who take the subway. – Warren Buffett

So the big day is here. You have evangelized your product across various circles and the good news is that a VC has stepped forward to invest in your company. So the hard work is all done! You can rest on your laurels, sign the term sheet that the VC has pushed across the table, and execute the sheet, trigger the stock purchase, voter and investor rights agreements, get the wire and you are up and running! Wait … sounds too good to be true, doesn’t it? And yes you are right! If only things were that easy. The devil is in the details. So let us go over some of the details that you need to watch out for.

1. First, term sheet does not trigger the wire. Signing a term sheet does not mean that the VC will invest in your company. The road is still long and treacherous. All the term sheet does is that it requires you to keep silent on the negotiations, and may even prevent you to shop the deal to anyone else. The key investment terms are laid out in the sheet and would be used in much greater detail when the stock purchase agreement, the investor rights agreement, the voting agreement and other documents are crafted.

2. Make sure that you have an attorney representing you. And more importantly, an attorney that has experience in the field and has reviewed a lot of such documents. As noted, the devil is in the details. A little “and” or “or” can put you back significantly. But it is just as important for you to know some of the key elements that govern an investment agreement. You can quiz your attorney on these because some of these are important enough to impact your operating degree of freedom in the company.The starting point of a term sheet is valuation of the company. You will hear the concept of pre-money valuation vs. post-money valuation. It is quite simple. The Pre-Money Valuation + Investment = Post-Money Valuation. In other words, Pre-money valuation refers to the value of a company not including external funding or the latest round of funding. Post-Money thus includes the pre-money plus the incremental injection of capital. Let us look at an example:

2. Make sure that you have an attorney representing you. And more importantly, an attorney that has experience in the field and has reviewed a lot of such documents. As noted, the devil is in the details. A little “and” or “or” can put you back significantly. But it is just as important for you to know some of the key elements that govern an investment agreement. You can quiz your attorney on these because some of these are important enough to impact your operating degree of freedom in the company.The starting point of a term sheet is valuation of the company. You will hear the concept of pre-money valuation vs. post-money valuation. It is quite simple. The Pre-Money Valuation + Investment = Post-Money Valuation. In other words, Pre-money valuation refers to the value of a company not including external funding or the latest round of funding. Post-Money thus includes the pre-money plus the incremental injection of capital. Let us look at an example:

Let’s explain the difference by using an example. Suppose that an investor is looking to invest in a start up. Both parties agree that the company is worth $1 million and the investor will put in $250,000.

The ownership percentages will depend on whether this is a $1 million pre-money or post-money valuation. If the $1 million valuation is pre-money, the company is valued at $1 million before the investment and after investment will be valued at $1.25 million. If the $1 million valuation takes into consideration the $250,000 investment, it is referred to as post-money. Thus in a pre-money valuation, the Investor owns 20%. Why? The total valuation is $1.25M which is $1M pre-money + $250K capital. So the math translates to $250K/$1,250K = 20%. If the investor says that they will value company $1M post-money, what they are saying is that they are actually giving you a pre-money valuation of $750K. In other words, they will own 25% of the company rather than 20%. Your ownership rights go down by 5% which, for all intents and purposes, is significant.

3. When a round of financing is done, security is exchanged in lieu of cash received. You already have common stock but these are not the securities being exchanged. The company would issue preferred stock. Preferred stock comes with certain rights, preferences, privileges and covenants. Compared to common stock, it is a superior security. There are a number of important rights and privileges that investors secure via a preferred stock purchase, including a right to a board seat, information rights, a right to participate in future rounds to protect their ownership percentage (called a pro-rata right), a right to purchase any common stock that might come onto the market (called a right of first refusal), a right to participate alongside any common stock that might get sold (called a co-sale right), and an adjustment in the purchase price to reflect sales of stock at lower prices (called an anti-dilution right). Let us examine this in greater detail now. There are two types of preferred. The regular vanilla Convertible Preferred and the Participating Preferred. As the latter name suggests, the Participating Preferred allows the VC to receive back their invested capital and the cumulative dividends, if any before common stockholders (that is you), but also enables them to participate on an as-converted basis in the returns to you, the common stockholder. Here is the math:Let us say company raises $3M at a $3M pre-money valuation. As mentioned before in point (3), the stake is 50%-50% owner-investor.

Let us say company sells for $25M. Now the investor has participating preferred or convertible preferred. How does the difference impact you, the stockholder or the founder. Here goes!

i. Participating Preferred. Investor gets their $3M back. There is still $22M left in the coffers. Investor splits 50-50 based on their participating preferred. You and Investor both take home $11M from the residual pool. Investor has $14M, and you have $11M. Congrats!

ii. Convertible Preferred. Investor gets 50% or $12.5M and you get the same – $12.5M. In other words, convertible preferred just got you a few more drinks at the bar. Hearty Congratulations!

Bear in mind that if the Exit Value is lower, the difference becomes more meaningful. Let us say exit was $10M. The Preferred participant gets $3M + $3.5M = $6.5M while you end up with $3.5M.

4. One of the key provisions is Liquidation Preferences. It can be a ticking time bomb. Careful! Some investors may sometimes ask for a multiple of their investment as a preference. This provision provides downside protection to investors. In the event of liquidation, the company has to pay back the capital injected for preferred. This would mean a 1X liquidation preference. However, you can have a 2X liquidation preference which means the investor will get back twice as much as what they injected. Most liquidation preferences range from 1X to 2X, although you can have higher liquidation preference multiples as well. However, bear in mind that this becomes important only when the company is forced to liquidate and sell of their assets. If all is gung-ho, this is a silent clause and no sweat off your brow.

4. One of the key provisions is Liquidation Preferences. It can be a ticking time bomb. Careful! Some investors may sometimes ask for a multiple of their investment as a preference. This provision provides downside protection to investors. In the event of liquidation, the company has to pay back the capital injected for preferred. This would mean a 1X liquidation preference. However, you can have a 2X liquidation preference which means the investor will get back twice as much as what they injected. Most liquidation preferences range from 1X to 2X, although you can have higher liquidation preference multiples as well. However, bear in mind that this becomes important only when the company is forced to liquidate and sell of their assets. If all is gung-ho, this is a silent clause and no sweat off your brow.

5. Redemption rights. The right of redemption is the right to demand under certain conditions that the company buys back its own shares from its investors at a fixed price. This right may be included to require a company to buy back its shares if there has not been an exit within a pre-determined period. Failure to redeem shares when requested might result in the investors gaining improved rights, such as enhanced voting rights.

6. The terms could demand that a certain option pool or a pot of stock is kept aside for existing and future employees, or other service providers. It could be a range anywhere between 10-20% of the total stock. When you reserve this pool, you are cutting into your ownership stake. In those instances when you have series of financings and each financing requires you to set aside a small pool, it dilutes you and your previous investors. In general, the way these pools are structured is to give you some headroom up to at least 24 months to accommodate employee growth and providing them incentives. The pool only becomes smaller with the passage of time.

7. Another term is the Anti-Dilution Provision. In its simplest form, anti-dilution rights are a zero- sum game. No one has an advantage over the other. However, this becomes important only when there is a down round. A down round basically means that the company is valued lower in subsequent financing than previously. A company valued at $25M in Series A and $15M in Series B – the Series B would be considered a down round. Two Types of Anti-Dilution:

Full ratchet Anti-Dilution: If the new stock is priced lower than prior stock, the early investor has a clause to convert their shares to the new price. For example, if prior investor paid $1.00 and then it was reset in a later round to $0.50, then the prior investors will have 2X rights to common stock. In other words, you are hit with major dilution as are the later investors. This clause is a big hurdle for new investors.

Weighted Average Anti-Dilution. Old investor’s share is adjusted in proportion to the dilution impact of a down round

8. Pay to Play. These are clauses that work in your, the Company, favor. Basically, investors have to invest some money in later financings, and if they do not – their rights may be reduced. However, having these clauses may put your mind at ease, but may create problems in terms of syndicating or getting investments. Some investors are reluctant to put their money in when there are pay to play clauses in the agreement.

9. Right of First Refusal. A company has no obligation to sell stock in future financing rounds to existing investors. Some investors would like to participate and may seek pro-rata participating to keep their ownership stake the same post-financing. Some investors may even want super pro-rata rights which means that they be allowed to participate to such an extent that their new ownership in the company is greater than their previous ownership stake.

10. Board of Directors. A large board creates complexity. Preferable to have a small but strategic board. New investors will require some representation. If too many investors request representation, the Company may have smaller internal representatives and may be outvoted on certain issues. Be aware of the dynamics of a mushrooming board!

11.Voting Rights. Investors may request certain veto authority or have rights to vote in favor of or against a corporate initiative. Company founders may want super-voting rights to exercise greater control. These matters are delicate and going one way or the other may cause personal issues among the participants. However, these matters can be easily resolved by essentially having carve-outs that spell out rights and encumbrances.

12.Drag Along Provision. Might create an obligation on all shareholders of the company to sell their shares to a potential purchaser if a certain percentage of the shareholders (or of a specific class of shareholders) votes to sell to that purchaser. Often in early rounds drag along rights can only be enforced with the consent of those holding at least a majority of the shares held by investors. These rights can be useful in the context of a sale where potential purchasers will want to acquire 100% of the shares of the company in order to avoid having responsibilities to minority shareholders after the acquisition. Many jurisdictions provide for such a process, usually when a third party has acquired at least 90% of the shares.

13.Representations and Warranties. Venture capital investors expect appropriate representations and warranties to be provided by key founders, management and the company. The primary purpose of the representations and warranties is to provide the investors with a complete and accurate understanding of the current condition of the company and its past history so that the investors can evaluate the risks of investing in the company prior to subscribing for their shares. The representations and warranties will typically cover areas such as the legal existence of the company (including all share capital details), the company’s financial statements, the business plan, asset ownership (in particular intellectual property rights), liabilities (contingent or otherwise), material contracts, employees and litigation. It is very rare that a company is in a perfect state. The warrantors have the opportunity to set out issues which ought to be brought to the attention of the new investors through a disclosure letter or schedule of exceptions. This is usually provided by the warrantors and discloses detailed information concerning any exceptions to or carve-outs from the representations and warranties. If a matter is referred to in the disclosure letter the investors are deemed to have notice of it and will not be able to claim for breach of warranty in respect of that matter. Investors expect those providing representations and warranties about the company to reimburse the investors for the diminution in share value attributable to the representations and warranties being inaccurate or if there are exceptions to them that have not been fully disclosed. There are usually limits to the exposure of the warrantors (i.e. a dollar cap on the amount that can be recovered from individual warrantors). These are matters for negotiation when documentation is being finalized. The limits may vary according to the severity of the breach, the size of the investment and the financial resources of the warrantors. The limits which typically apply to founders are lower than for the company itself (where the company limit will typically be the sum invested or that sum plus a minimum return).

14. Information Rights. In order for venture capital investors to monitor the condition of their investment, it is essential that the company provides them with certain regular updates concerning its financial condition and budgets, as well as a general right to visit the company and examine its books and records. This sometimes includes direct access to the company’s auditors and bankers. These contractually defined obligations typically include timely transmittal of annual financial statements (including audit requirements, if applicable), annual budgets, and audited monthly and quarterly financial statements.

15. Exit. Venture capital investors want to see a path from their investment in the company leading to an exit, most often in the form of a disposal of their shares following an IPO or by participating in a sale. Sometimes the threshold for a liquidity event or will be a qualified exit. If used, it will mean that a liquidity event will only occur, and conversion of preferred shares will only be compulsory, if an IPO falls within the definition of a qualified exit. A qualified exit is usually defined as a sale or IPO on a recognized investment exchange which, in either case, is of a certain value to ensure the investors get a minimum return on their investment. Consequently, investors usually require undertakings from the company and other shareholders that they will endeavor to achieve an appropriate share listing or trade sale within a limited period of time (typically anywhere between 3 and 7 years depending on the stage of investment and the maturity of the company). If such an exit is not achieved, investors often build in structures which will allow them to withdraw some or the entire amount of their investment.

16. Non-Compete, Confidentiality Agreements. It is good practice for any company to have certain types of agreements in place with its employees. For technology start-ups, these generally include Confidentiality Agreements (to protect against loss of company trade secrets, know-how, customer lists, and other potentially sensitive information), Intellectual Property Assignment Agreements (to ensure that intellectual property developed by academic institutions or by employees before they were employed by the company will belong to the company) and Employment Contracts or Consultancy Agreements (which will include provisions to ensure that all intellectual property developed by a company’s employees belongs to the company). Where the company is a spin-out from an academic institution, the founders will frequently be consultants of the company and continue to be employees of the academic institution, at least until the company is more established. Investors also seek to have key founders and managers enter into Non-compete Agreements with the company. In most cases, the investment in the company is based largely on the value of the technology and management experience of the management team and founders. If they were to leave the company to create or work for a competitor, this could significantly affect the company’s value. Investors normally require that these agreements be included in the Investment Agreement as well as in the Employment/Consultancy Agreements with the founders and senior managers, to enable them to have a right of direct action against the founders’ and managers if the restrictions are breached.

Convertible Debt: What, How, Plus, Minus?

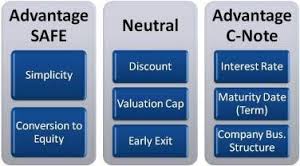

Convertible Debt is also called convertible loans or convertible notes. This is a common method of financing for early stage companies. Typically, an investor or a group of investors (investor syndicate) extends a loan to a company that could later convert to an equity instrument. Like any debt, it is an interest bearing instrument. However, the key element in this form of financing is that the investors will get equity at a discount when the Company raises a Series A round. In other cases, it could be a warrant issue. In most instances, there is a cap on the valuation at which the debt will convert.

Hence, there are four key components of convertible debt:

- Convertible Debt has an interest.

- Convertible Debt has a discount

- Convertible Debt may have warrants

- Valuation at which Debt converts is capped.

Let us discuss each of these in detail.

Convertible Debt is interest bearing.

Like any debt, the borrower has a loan on their balance sheet. They are responsible for the principal and the interest. The interest is simple interest rate, and there is a fixed due date (or “maturity date”) for repayment of the amount borrowed. In other words, if there is no Series A funding before the maturity of the convertible debt, there could be some problems for the company. In an extreme case, the note holder can force the company into bankruptcy, unless the startup can renegotiate and extend the terms. The appropriate interest rate for convertible debt could be anywhere between 6% up to 10%. The Applicable Federal Rates (AFRs) can establish the lowest legally allowable interest rates.

Convertible Note Discount.

As a sweetener, the note will have an automatic conversion discount feature by which the investor will exchange the convertible debt for shares of a Series A Preferred Stock at a discount to the price per share paid by a VC in a Qualified Financing Round. Here is how this works:

A) Angel invests $100,000 in the startup company.

B) Startup issues the convertible note for $100K which has an interest and maturity date.

C) The Note has an automatic conversion feature at $1M with a conversion discount equal to 20%.

D) Now, let us say that the Startup closes $1M Series A Preferred Stock at $1 per share.

E) The Angel thus gets the shares at 80 cents.

F) So Angel gets $100,000/$0.80 per share of the Series A Preferred which totals to 125,000 shares.

Convertible Notes may have warrants.

The warrants are very similar to options. In a typical convertible note, the Warrant will be an option for whatever security is sold in the next round. It is often expressed in terms of “warrant coverage percentage”. A 20% warrant coverage means that you can take the same $1M, multiply by 20%, and the Warrant independently will enable you to get $200K of additional securities in the next round. For example, let us say a Series A round is $4M (Company has raised $4M). The warrant coverage kicks in and now the size of the round becomes $5.2M. ($4M New Fund + $1M size of Note + $200K warrant coverage = $5.2M) So there is a dilution impact of $1.2M for the $1M of angel cash that was extended in the form of the Note with the Warrant Coverage.

Convertible Notes Caps

Cap is a term that protects the angel investor and puts a ceiling on the conversion price of debt. This is seen mostly in seed financings. For example, angel invests a $100K in a company at 20% discount and thinks that the pre-money valuation maxes out at $3M. If the angel was correct and the valuation was indeed at $3M (assume $1.00 for preferred share) , then the angel would have 125,000 shares. That would be 125,000 shares/(3M shares + 125,000) = 4%. The investor would own 4% immediately upon Qualified Financing.

However, assume that the company is hugely successful and the pre-money valuation is assessed at $10M. Let us say that the preferred stock is at $1.00. So now you have 10M shares. Angel Investor gets 125,000 shares. Then the Investor is diluted down to 1.23%. (125K shares/ (10M shares + 125K shares)). Hence the higher the valuation in Series A, the investor gets diluted down further. Hence they use Convertible Notes Caps as a protection to their downside dilution risk. The cap sets a limit for how much the Company can raise before the investor’s shares stop getting diluted. It sets an upper limit. So if the investor in the above example sets a cap at $5M, then the discount would increase to offset the additional dilution that occurred. So in this case, the investor actually gets a 50% discount, not a 20% discount. It is important to note that the cap is structured as either or – in other words, the angel investor gets the value of the greater of the two discounts.

Advantages of Convertible Debt Financing

- Easy to raise

- Paperwork could be less than 10 pages.

- Quick turnaround time to get this signed off

- Terms are generally clearly defined

- Legal Expenses are typically less than $5000-$8000.

- Company can defer the valuation discussion until a later date

- Notes have fewer rights than Equity. Investors in Notes have less say in the direction and execution of company plans.

Disadvantages of Convertible Debt Financing

- It is a loan and there is a maturity date on the loan. If financing does not occur, the investor can recall the note and force the company into bankruptcy.

- Incentives are not necessarily aligned. Company wants more valuation in Series A but investor would want less to own larger pool. With a cap, they accomplish that but the Company owners are diluted down depending on cap or size of discount.

- Size of discount or cap could create problems for the Company seeking Series A. Series A investors might force a renegotiation thus increasing legal and other costs to the Company. A low valuation cap could adversely affect the owners of the Company.

- Conversion to equity would mean equivalent privileges with respect to rights. Bear in mind that angel investors are generally not professional VC’s and each of them have very different expertise. Equivalent rights for the different expertise may create problems and issues among all parties involved.

- Convertible Notes may have senior preferences. In the event of liquidation, the Note Holders are first in line to get their money back.

- Some angel investors may want subscription rights or super pro-rata rights to the next round of funding. This is to prevent their dilution. So they may want to have the option to participate up to a certain percentage of the next round. In other words, if the round is $5M, the subscription right might specify that the investor can participate up to 30% and that would mean that the investor has a bigger seat on the table. Such clauses may not be favorably looked at by Series A investor and these clauses could hold up financing.