Blog Archives

Transforming CFO Roles into Internal Venture Capitalists

I learned early in my career that capital is more than balance and flow. It is the spark that can ignite ambition or smother possibility. During my graduate studies in finance and accounting, I treated projects as linear investments with predictable returns. Yet, across decades in global operating and FP&A roles, I came to see that business is not linear. It progresses in phases, through experiments, serendipity, and choices that either accelerate or stall momentum. Along the way, I turned to literature that shaped my worldview. I grew familiar with Geoffrey West’s Scale, which taught me to see companies as complex adaptive systems. I devoured “The Balanced Scorecard ” and “Measure What Matters,” which helped me integrate strategy with execution. I studied Hayek, Mises, and Keynes, and found in their words the tension between freedom and structure that constantly shapes business decisions. In my recent academic detour into data analytics at Georgia Tech, I discovered the tools I needed to model ambiguity in a world where uncertainty is the norm.

This rich intellectual fabric informs my belief that finance must behave like an internal venture capitalist. The traditional role of the CFO often resembled a gatekeeper. We controlled capital, enforced discipline, and ensured compliance. But compliance alone does not drive growth. It manages risk. What the modern CFO must offer is structured exploration. We must fund bets, define guardrails, measure outcomes, and redeploy capital against the most successful experiments. And just as external investors sunset underperforming ventures, internal finance must have the courage to pull the plug on underwhelming initiatives, not as punishment, but as deliberate reallocation of attention and energy.

The internal-VC mindset positions finance at the intersection of strategy, data, and execution. It is not about checklists. It is about pattern recognition. It is not about spreadsheets. It is about framing. And it is not about silence. It is about active dialogue with product owners, marketers, sales leaders, analysts, engineers, and legal counsel. To be an internal venture capitalist requires two shifts. One is cognitive. We must see every budget allocation as a discrete business experiment with its own risk profile and value potential. The second shift is cultural. We must build circuits of accountability, learning, and decision velocity that match our capital cadence.

My journey toward this philosophy began when I realized that capital allocations in corporate settings often followed the path of least resistance. Teams that worked well together or those that asked loudly received priority. Others faded until the next planning cycle. That approach may work in stable environments. It fails gloriously in high-velocity, venture-backed companies. In those settings, experimentation must be systematic, not happenstance.

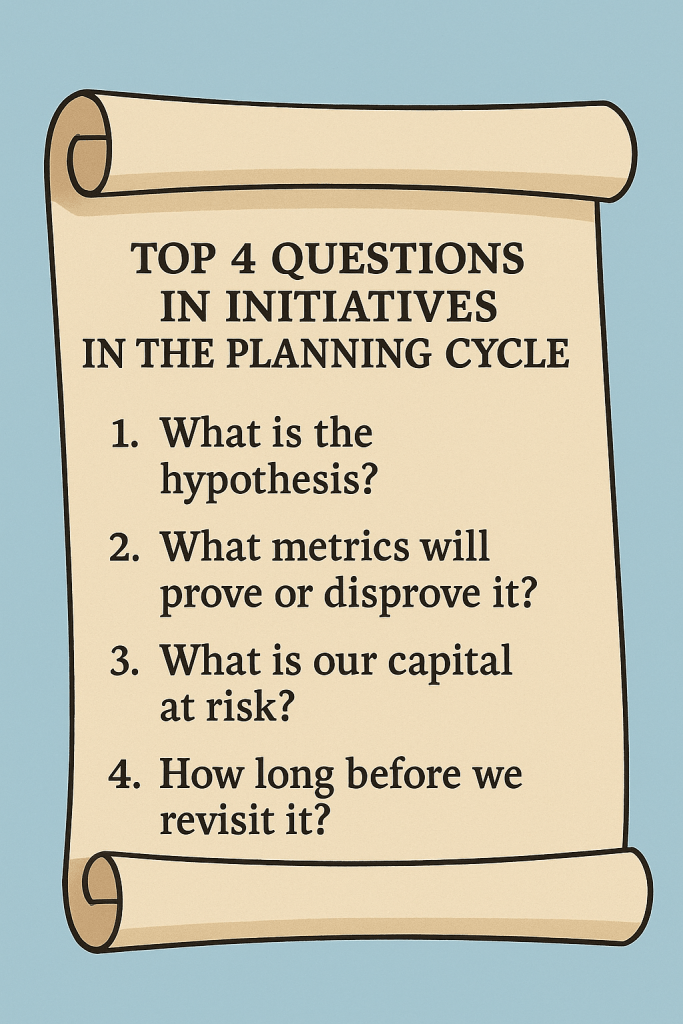

So I began building a simple framework with my FP&A teams. Every initiative, whether product expansion, marketing pilot, or infrastructure build, entered the planning process as an experiment.

We asked four questions: What is the hypothesis? What metrics will prove or disprove it? What is our capital at risk? And how long before we revisit it? We mandated a three-month trial period for most efforts. We developed minimal viable KPIs. We built lightweight dashboards that tracked progress. We used SQL and R to analyze early signals. We brought teams in for biweekly check-ins. Experiment status did not remain buried in a spreadsheet. We published it alongside pipeline metrics and cohort retention curves.

This framework aligned closely with ideas I first encountered in The Execution Premium. Strategy must connect to measurement. Measurement must connect to resource decisions. In external venture capital, the concept is straightforward: money flows to experiments that deliver results. In internal operations, we often treat capital as a product of the past. That must change. We must fund with intention. We must measure with rigor. We must learn at pace. And when experiments succeed, we scale decisively. When they fail, we reallocate quickly and intelligently.

One internal experiment I recently led involved launching a tiered pricing add-on. The sales team had anecdotal feedback from prospects. The product team wanted space to test. And finance wanted to ensure margin resilience. We framed this as a pilot rather than a formal release. We developed a compact P&L model that simulated the impact on gross margin, NRR sensitivity, and churn risk. We set a two-month runway and tracked usage and customer feedback in near real time. And when early metrics showed that a small segment of customers was willing to pay a premium without increasing churn, we doubled down and fast-tracked the feature build. It scaled within that quarter.

This success came from intentional framing, not luck. It came from seeing capital allocation as orchestration, not allotment. It came from embedding finance deep into decision cycles, not simply reviewing outputs. It came from funding quickly, measuring quickly, and adjusting even faster.

That is what finance as internal VC looks like. It does not rely on permission. It operates with purpose.

Among the books that shaped my thinking over the decades, Scale, The Balanced Scorecard, and Measure What Matters stood out. Scale taught me to look for leverage points in systems rather than single knobs. The Balanced Scorecard reminded me that value is multidimensional. Measure What Matters reinforced the importance of linking purpose with performance. Running experiments internally draws directly from those ideas, weaving systems thinking with strategic clarity and an outcome-oriented approach.

If you lead finance in a Series A, B, or C company, ask yourself whether your capital allocation process behaves like a venture cycle or a budgeting ritual. Do you fund pilots with measurable outcomes? Do you pause bets as easily as you greenlight them? Do you embed finance as an active participant in the design process, or simply as a rubber stamp after launch? If not, you risk becoming the bottleneck, not the catalyst.

As capital flows faster and expectations rise higher for Series A through D companies, finance must evolve from a back-office steward to an active internal investor. I recall leading a capital review where representatives from product, marketing, sales, and finance came together to evaluate eight pilot projects. Rather than default to “fund everything,” we applied simple criteria based on learnings from works like The Lean Startup and Thinking in Bets. We asked: If this fails, what will we learn? If this succeeds, what capabilities will scale? We funded three pilots, deferred two, and sunsetted one. The deferrals were not rejections. They were timely reflections grounded in probability and pragmatism.

That decision process felt unconventional initially. Leaders expect finance to compute budgets, not coach choices. But that shift in mindset unlocked several outcomes in short order. First, teams began designing their proposals around hypotheses rather than hope. Second, they began seeking metric alignment earlier. And third, they showed new respect for finance—and not because we held the purse strings, but because we invested intention and intellect, not just capital.

To sustain that shift, finance must build systems for experimentation. I came to rely on three pillars: capital scoring, cohort ROI tracking, and disciplined sunset discipline. Capital scoring means each initiative is evaluated based on risk, optionality, alignment with strategy, and time horizon. We assign a capital score and publish it alongside the ask. This forces teams to pause. It sparks dialogue.

Cohort ROI tracking means we treat internal initiatives like portfolio lines. We assign a unique identifier to every project and track KPIs by cohort over time. This allowed us to understand not only whether the experiment succeeded, but also which variables: segment, messaging, feature scope, or pricing-driven outcomes. That insight fashions future funding cycles.

Sunset discipline is the hardest. We built expiration triggers into every pitch. We set calendar checkpoints. If the metrics do not indicate forward progress, the initiative is terminated. Without that discipline, capital accumulates, and inertia settles. With it, capital remains fluid, and ambitious teams learn more quickly.

These operational tools combined culture and structure. They created a rhythm that felt venture-backed and venture-smart, not simply operational. They further closed the distance between finance and innovation.

At one point, the head of product slid into my office. He said, “I feel like we are running experiments at the speed of ideas, not red tape.” That validation meant everything. And it only happened because we chose to fund with parameters, not promote with promises.

But capital is not the sole currency. Information is equal currency. Finance must build metrics infrastructure to support internal VC behavior. We built a “value ledger” that connected capital flows to business outcomes. Each cohort linked capital expenditure to customer acquisition, cost-to-serve, renewal impact, and margin projection. We pulled data from Salesforce, usage logs, and billing systems—sometimes manually at first—into simple, weekly-updated dashboards. This visual proximity reduced friction. Task owners saw the impact of decisions across time, not just in retrospective QBRs.

I drew heavily on my analytics training at the Georgia Institute of Technology for this. I used R to run time series on revenue recognition patterns. I used Arena to model multi-cohort burn, headcount scaling, and feature adoption. These tools translated the capital hypothesis into numerical evidence. They didn’t require AI. They needed discipline and a systems perspective.

Embedded alongside metrics, we also built a learning ritual. Every quarter, we held a “portfolio learning day.” All teams presented successes, failures, surprises, and subsequent bets. Engineering leaders shared how deployment pipelines impacted adoption. Customer success directors shared early signs of account expansion. Sales leaders shared win-rate anomalies against cohort tags. Finance hosted, not policed. We shared capital insights, not criticism. Over time, the portfolio day became a highly coveted ritual, serving as a refresher on collective strategy and emergent learning.

The challenge we faced was calibration. Too few experiments meant growth moves slowly. Too many created confusion. We learned to apply portfolio theory: index some bets to the core engine, keep others as optional, and let a few be marginal breakers. Finance segmented investments into Core, Explore, and Disrupt categories and advised on allocation percentages. We didn’t fix the mix. We tracked it. We nudged, not decreed. That alignment created valuation uplift in board conversations where growth credibility is a key metric.

Legal and compliance leaders also gained trust through this process. We created templated pilot agreements that embedded sunset clauses and metrics triggers. We made sunset not an exit, but a transition into new funding or retirement. Legal colleagues appreciated that we reduced contract complexity and trimmed long-duration risk. That cross-functional design meant internal VC behavior did not strain governance, but it strengthened it.

By the time this framework matured at Series D, we no longer needed to refer to it as “internal VC.” It simply became the way we did business. We stopped asking permission. We tested and validated fast. We pulled ahead in execution while maintaining discipline. We did not escape uncertainty. We embraced it. We harnessed it through design.

Modern CFOs must ask themselves hard questions. Is your capital planning a calendar ritual or a feedback system? Do you treat projects as batch allocations or timed experiments? Do you bury failure or surface it as insight? If your answer flags inertia, you need to infuse finance with an internal VC mindset.

This approach also shapes FP&A culture. Analysts move from variance detectives to learning architects. They design evaluation logic, build experiment dashboards, facilitate retrospectives, and coach teams in framing hypotheses. They learn to act more like consultants, guiding experimentation rather than policing spreadsheets. That shift also motivates talent; problem solvers become designers of possibilities.

When I reflect on my intellectual journey, from the Austrian School’s view of market discovery to complexity theory’s paradox of order, I see finance as a creative, connective platform. It is not just about numbers. It is about the narrative woven between them. When the CFO can say “yes, if…” rather than “no,” the organization senses an invitation rather than a restriction. The invitation scales faster than any capital line.

That is the internal VC mission. That is the modern finance mandate. That is where capital becomes catalytic, where experiments drive compound impact, and where the business within the business propels enterprise-scale growth.

The internal VC experiment is ongoing. Even now, I refine the cadence of portfolio days. Even now, I question whether our scoring logic reflects real optionality. Even now, I sense a pattern in data and ask: What are we underfunding for future growth? CFOs who embrace internal VC behavior find themselves living at the liminal point between what is and what could be. That is both exhilarating and essential.

If this journey moves you, reflect on your own capital process. Where can you embed capital scoring, cohort tracking, and sunset discipline? Where can you shift finance from auditor to architect? Where can you help your teams see not just what they are building, but why it matters, how it connects, and what they must learn next?

I invite you to share those reflections with your network and to test one pilot in the next 30 days. Run it with capital allocation as a hypothesis, metrics as feedback, and finance as a partner. That single experiment may open the door to the next stage of your company’s growth.

Internal versus External Scale

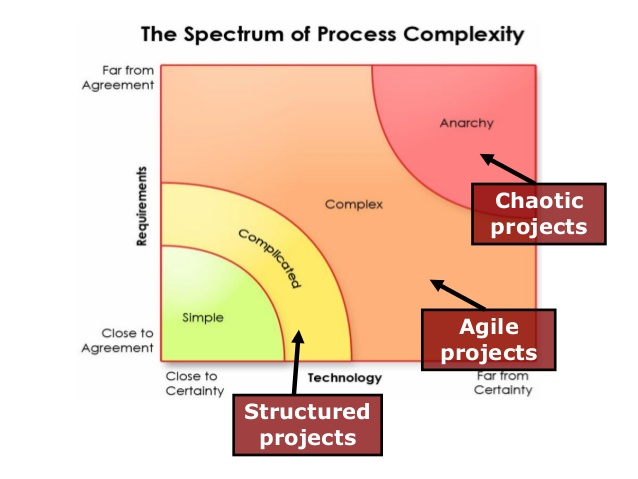

This article discusses internal and external complexity before we tee up a more detailed discussion on internal versus external scale. This chapter acknowledges that complex adaptive systems have inherent internal and external complexities which are not additive. The impact of these complexities is exponential. Hence, we have to sift through our understanding and perhaps even review the salient aspects of complexity science which have already been covered in relatively more detail in earlier chapter. However, revisiting complexity science is important, and we will often revisit this across other blog posts to really hit home the fundamental concepts and its practical implications as it relates to management and solving challenges at a business or even a grander social scale.

A complex system is a part of a larger environment. It is a safe to say that the larger environment is more complex than the system itself. But for the complex system to work, it needs to depend upon a certain level of predictability and regularity between the impact of initial state and the events associated with it or the interaction of the variables in the system itself. Note that I am covering both – complex physical systems and complex adaptive systems in this discussion. A system within an environment has an important attribute: it serves as a receptor to signals of external variables of the environment that impact the system. The system will either process that signal or discard the signal which is largely based on what the system is trying to achieve. We will dedicate an entire article on system engineering and thinking later, but the uber point is that a system exists to serve a definite purpose. All systems are dependent on resources and exhibits a certain capacity to process information. Hence, a system will try to extract as many regularities as possible to enable a predictable dynamic in an efficient manner to fulfill its higher-level purpose.

Let us understand external complexities. We can interchangeably use the word environmental complexity as well. External complexity represents physical, cultural, social, and technological elements that are intertwined. These environments beleaguered with its own grades of complexity acts as a mold to affect operating systems that are mere artifacts. If operating systems can fit well within the mold, then there is a measure of fitness or harmony that arises between an internal complexity and external complexity. This is the root of dynamic adaptation. When external environments are very complex, that means that there are a lot of variables at play and thus, an internal system has to process more information in order to survive. So how the internal system will react to external systems is important and they key bridge between those two systems is in learning. Does the system learn and improve outcomes on account of continuous learning and does it continually modify its existing form and functional objectives as it learns from external complexity? How is the feedback loop monitored and managed when one deals with internal and external complexities? The environment generates random problems and challenges and the internal system has to accept or discard these problems and then establish a process to distribute the problems among its agents to efficiently solve those problems that it hopes to solve for. There is always a mechanism at work which tries to align the internal complexity with external complexity since it is widely believed that the ability to efficiently align the systems is the key to maintaining a relatively competitive edge or intentionally making progress in solving a set of important challenges.

Internal complexity are sub-elements that interact and are constituents of a system that resides within the larger context of an external complex system or the environment. Internal complexity arises based on the number of variables in the system, the hierarchical complexity of the variables, the internal capabilities of information pass-through between the levels and the variables, and finally how it learns from the external environment. There are five dimensions of complexity: interdependence, diversity of system elements, unpredictability and ambiguity, the rate of dynamic mobility and adaptability, and the capability of the agents to process information and their individual channel capacities.

If we are discussing scale management, we need to ask a fundamental question. What is scale in the context of complex systems? Why do we manage for scale? How does management for scale advance us toward a meaningful outcome? How does scale compute in internal and external complex systems? What do we expect to see if we have managed for scale well? What does the future bode for us if we assume that we have optimized for scale and that is the key objective function that we have to pursue?