Category Archives: Employee Engagement

Transforming Finance: From ERP to Real-Time Decision Making

There was a time when the role of the CFO could be summarized with a handful of verbs: report, reconcile, allocate, forecast. In the 20th century, the finance office was a bastion of structure and control. The CFO was the high priest of compliance and the gatekeeper of capital. The systems were linear, the rhythms were quarterly, and the decisions were based on historical truths.

That era has passed. In its place emerges the Digital CFO 3.0 – a new kind of enterprise leader who moves beyond control towers and static spreadsheets to architect digital infrastructure, orchestrate intelligent systems, and enable predictive, adaptive, and real-time decision-making across the enterprise.

This is not a change in tools. It is a change in mindset, muscle, and mandate.

The Digital CFO 3.0 is not just a steward of financial truth. They are a strategic systems architect, a data supply chain engineer, and a design thinker for the cognitive enterprise. Their domain now includes APIs, cloud data lakes, process automation, AI-enabled forecasting, and trust-layer governance models. They must reimagine the finance function not as a back-office cost center, but as the neural core of a learning organization.

Let us explore the core principles, capabilities, and operating architecture that define this new role, and how today’s finance leaders must prepare to build the infrastructure of the future enterprise.

1. From Monolithic ERP to Modular Intelligence

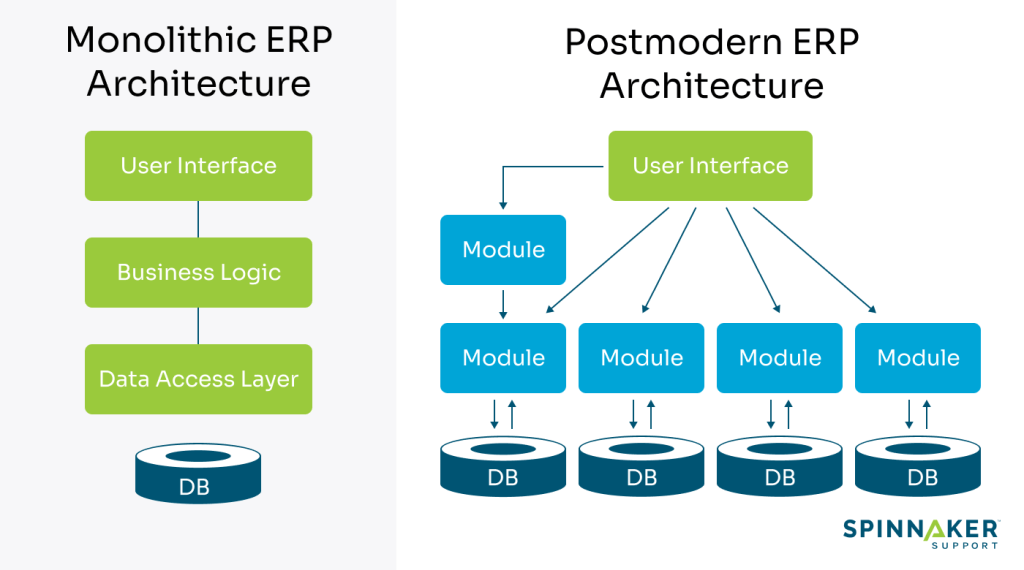

Traditional finance infrastructure was built on monolithic ERP systems – massive, integrated, but inflexible. Every upgrade was painful. Data latency was high. Insight was slow.

The Digital CFO 3.0 shifts toward a modular, composable architecture. Finance tools are API-connected, event-driven, and cloud-native. Data moves in real time through finance operations, from procure-to-pay to order-to-cash.

- Core systems remain but are surrounded by microservices for specific tasks: forecasting, scenario modeling, spend analytics, compliance monitoring.

- Data lakes and warehouses serve as integration layers, decoupling applications from reporting.

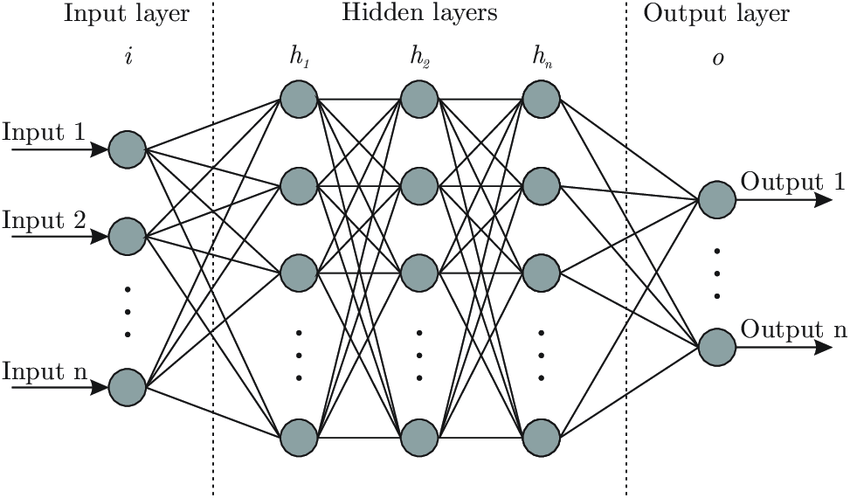

- AI and ML modules plug into these environments to generate insights on demand.

This architecture enables agility. New use cases can be spun up quickly. Forecasting models can be retrained in hours, not months. Finance becomes a responsive, intelligent grid rather than a transactional pipe.

2. Finance as a Real-Time Operating System

In legacy models, finance operated in batch mode: monthly closes, quarterly forecasts, annual planning. But the modern enterprise operates in real time. Markets shift hourly. Customer behavior changes daily. Capital decisions must respond accordingly.

The Digital CFO builds a real-time finance engine:

- Continuous Close: Transactions are reconciled daily, not monthly. Variances are flagged immediately. The books are always nearly closed.

- Rolling Forecasting: Plans update with each new signal – not by calendar, but by context.

- Embedded Analytics: Metrics travel with the business – inside CRM, procurement, inventory, and workforce systems.

- Streaming KPIs: Finance watches the enterprise like a heart monitor, not a photograph.

This changes how decisions are made. Instead of waiting for reports, leaders ask questions in the flow of business – and get answers in seconds.

3. Trust by Design: The New Governance Layer

As data velocity increases, so does the risk of error, bias, and misinterpretation. The CFO has always been a guardian of trust. But for the Digital CFO 3.0, this mandate extends to the digital trust layer:

- Data Lineage: Every number is traceable. Every transformation is logged.

- Model Governance: AI models used in finance must be explainable, auditable, and ethical.

- Access Control: Fine-grained permissions ensure only the right people see the right numbers.

- Validation Rules: Embedded in pipelines to flag anomalies before they reach the dashboard.

Trust is not a byproduct of strong reporting. It is an outcome of intentional design.

4. Orchestrating the Intelligent Workflow

In the digital enterprise, no team operates in isolation. Sales, operations, procurement, HR are interconnected. The Digital CFO 3.0 builds infrastructure to orchestrate intelligent workflows across silos.

- AP automation connects with vendor portals and treasury systems.

- Forecast adjustments trigger alerts to sourcing and demand planning teams.

- Employee cost changes ripple through headcount plans and productivity dashboards.

This orchestration requires more than software. It demands process choreography and data interoperability. The CFO becomes the conductor of a distributed, dynamic finance system.

5. Redesigning Talent for a Cognitive Finance Team

Digital infrastructure is only as powerful as the team that runs it. The finance org of the future looks different:

- Analysts become insight designers, curating stories from signals.

- Controllers become data quality stewards.

- FP&A teams become simulation strategists.

- Finance business partners become embedded value engineers.

The Digital CFO invests in technical fluency, data storytelling, and systems thinking. Upskilling is continuous. Learning velocity becomes a core KPI.

6. From Reporting the Past to Architecting the Future

Ultimately, the Digital CFO 3.0 is not building systems to describe yesterday. They are designing infrastructure to anticipate tomorrow:

- Capex investments are modeled across geopolitical scenarios.

- ESG metrics are embedded into supplier scoring and budget cycles.

- Strategic choices are evaluated with real option models and probabilistic simulations.

- M&A integration plans are automated, with finance playbooks triggered by transaction type.

The finance function becomes a predictive nerve center, informing everything from product pricing to market entry.

Conclusion: The CFO as Enterprise Architect

The shift to Digital CFO 2.0 is not optional. It is inevitable. Markets are faster. Technology is smarter. Stakeholders expect more. What was once a support function is now a strategic command center.

This is not about buying tools. It is about designing an operating system for the enterprise that is intelligent, adaptive, and deeply aligned with value creation.

The future CFO does not just report results. They engineer outcomes. They do not just forecast growth. They architect the infrastructure to make it happen.

CFOs as Venture Capitalists: Rethinking ERP Strategies

Most CFOs view their ERP systems the way civil engineers view bridges—vital, expensive, and terrifying to replace. They are the arteries of the enterprise, moving data and dollars across finance and operations. Yet, despite all the cost and effort, most ERPs underperform their potential.

The reason is not lack of functionality—it is lack of imagination.

After leading multiple ERP transformations—from NetSuite and Sage and BaaN MRP implementations to a global rollout of Oracle Financials integrated with Hyperion and MicroStrategy, I have come to believe that the real return on ERP investment lies not in the code, but in the design philosophy.

It is time CFOs started thinking like venture capitalists and systems engineers.

From Infrastructure to Investment Portfolio

Traditional ERP thinking is defensive: avoid disruption, close the books, ensure compliance. It is the financial equivalent of playing not to lose.

But a venture capitalist asks a different question: where is the next multiple coming from?

We can treat ERP initiatives the same way—segmenting them into:

- Core Maintenance: compliance, upgrades, and security.

- Leverage Plays: automation, reporting, and workflow redesign.

- Optionality Bets: AI-powered forecasting, agentic automation, and embedded analytics.

This portfolio mindset ensures capital is allocated to where it generates the most operational leverage, not where it merely reduces anxiety.

The Power of Horizontal Thinking

Most ERP failures are not technical – they are architectural. Companies build vertical silos: Finance here, Procurement there, HR in another system. Each one optimized locally but misaligned globally.

The future belongs to horizontal, workstream-focused systems—built around flows like Order-to-Cash, Procure-to-Pay, and Record-to-Report.

Why does this matter? Because workstreams are where value flows. That is where automation compounds, latency disappears, and teams feel the impact of technology.

When I oversaw our Oracle-Hyperion-MicroStrategy global rollout, the biggest unlock did not come from adding modules. It came from aligning processes horizontally—so that planning, consolidation, and analytics spoke the same language. That is when the ERP stopped being a ledger and started being an intelligence engine.

Why Modularity Enables Agentic AI

Horizontal ERPs are, by nature, modular. Each component—finance, procurement, analytics—interacts through clean APIs and governed data layers. This modularity is exactly what Agentic AI systems need to thrive.

AI agents are not magic—they are orchestration tools. They need consistent structures, good metadata, and systems that can “talk” to each other. A modular ERP built on sound governance becomes the perfect substrate for AI copilots that can:

- Reconcile accounts automatically,

- Trigger proactive alerts for anomalies,

- Forecast cash flow in real time, and

- Suggest workflow optimizations based on patterns.

When the ERP is monolithic, AI is decorative. When it is modular, AI becomes multiplicative.

Designing for Hidden ROI

The hidden ROI zones are everywhere once you start looking:

- Process Acceleration – Automating intercompany eliminations or close cycles.

- Data Visibility – Converting stale reports into live dashboards.

- Workflow Integration – Syncing ERP with CRM, HRIS, and procurement to eliminate handoffs.

Each enhancement may look small, but compounded across a finance organization, they can save thousands of hours per year.

That is how venture thinking turns into financial engineering.

Metrics Boards Actually Care About

We do not measure ERP ROI in “go-live” dates anymore. We measure it in:

- Days to close,

- Time to insight,

- Cost per transaction, and

- Productivity per finance FTE.

These are tangible, board-level metrics that link system efficiency directly to enterprise value.

Governance: The Unsung Hero

The best ERPs die slowly—not from bugs, but from bloat. Over-customization, consultant dependence, and poor data hygiene suffocate agility.

Good governance means lean design, modular rollouts, transparent contracts, and internal ownership. It is less glamorous than AI, but without it, innovation becomes entropy.

Final Word: ERP as a Competitive Advantage

ERPs are not going away: they are the spine of the enterprise. But we can make them smarter, faster, and more horizontal.

When designed with modularity, governed with discipline, and infused with agentic intelligence, the ERP evolves from a cost center into a compounding asset.

The CFO who thinks like a venture capitalist and designs like a systems architect will find that the next great ROI story is already sitting inside the general ledger waiting to be unlocked.

Building Value in Private Equity: A Story of Growth and Time

The Big Idea

Some people think value is something you find like treasure hidden in a cave. But in private equity, value is not found. It is built. It grows the way cities, trees, or living systems grow—by following simple rules, adapting to change, and using energy wisely.

As Geoffrey West explains in Scale, all living and business systems follow patterns of growth and decay. A private equity investment is no different. It begins with a spark of belief, grows through learning and adjustment, and must fight against the natural pull of entropy which is the quiet slide toward disorder.

Building value is not about being clever once. It is about staying disciplined over time.

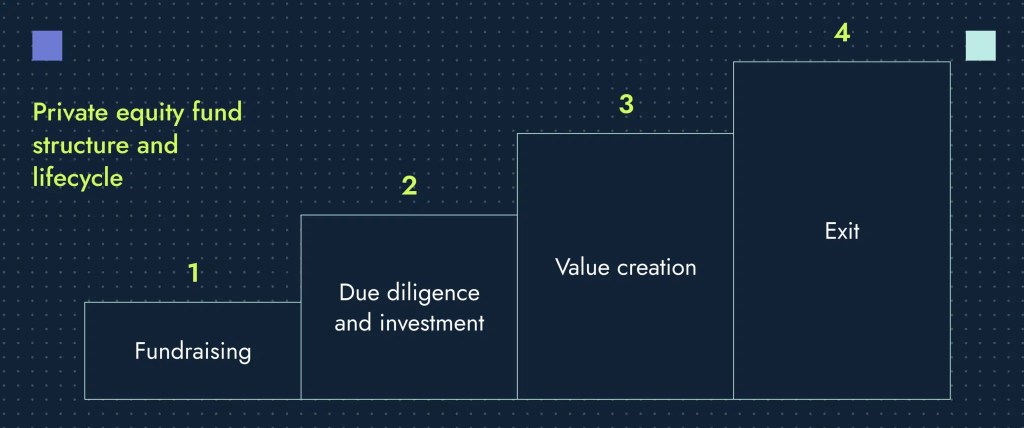

1. The Beginning: Choosing with Care

Before an investor buys a company, they face the most challenging question: What will be different because we own it?

In this stage, we do not just look at spreadsheets. We ask questions about people, processes, and potential. We look for “scaling rules”—places where minor improvements can multiply results. A good investor studies the system the way a biologist studies an ecosystem. Every number in the model connects to behavior, incentives, and feedback. You cannot fix what you don’t understand.

As someone who has spent decades in finance and operations, I have learned that the best deals start not with excitement, but with honesty. Ask challenging questions before signing the check. Anything you ignore before buying will hurt you later.

2. The First Hundred Days: From Paper to People

Once the deal closes, the real work begins. The first hundred days are like the early growth phase of a city or an organism which is where rhythm, energy, and culture take shape.

The key is not speed, but sequencing. Move too fast, and the organization breaks. Move too slowly, and energy fades. Early wins matter, but trust matters more.

The plan must be simple enough for everyone to understand. I often remind teams: “If the warehouse manager and the sales lead cannot explain the strategy in one sentence, it is not ready.”

As in complex systems, feedback loops keep things healthy. Weekly check-ins, small data dashboards, and short decision cycles build transparency. Trust is the oxygen of transformation—without it, even good plans suffocate.

3. The Middle Years: Fighting Entropy

Every growing system eventually slows down. In cities, it shows up as traffic jams. In companies, it appears as missed deadlines, tired teams, and too many reports.

This is entropy which is the quiet drift toward disorder. You cannot eliminate it, but you can manage it.

The middle years of a private equity investment test the investor’s patience. It is no longer about ideas; it is about maintenance. Which projects still matter? Which metrics still measure the right things? Which leaders are ready for the next phase?

I have seen this pattern repeatedly: the companies that survive entropy are the ones that stay curious. They ask, “Is this still working?” and “What signal are we missing?” Complexity thinking reminds us—adaptation, not rigidity, creates resilience.

4. The Exit: Leaving Gracefully

Exiting an investment is like a scientist passing their experiment to the next researcher. The goal is not to make it perfect; it is to make it understandable and repeatable.

A great exit story is clear and accurate. It does not hide mistakes; it shows learning. Buyers pay a premium for systems they can trust. That means clean data, steady teams, and a clear narrative of progress.

In my own career, the best exits were not the flashiest; they were the ones where the company kept growing long after we left. That is when you know value was built, not borrowed.

Leaving well is an act of leadership. It requires detachment and pride in what’s been created. The company should no longer depend on you. Like a child leaving home, it should stand on its own.

5. The Bigger Picture: Value as a Living System

When I read Geoffrey West’s work, I saw private equity through a new lens. A company is a living system—it consumes energy (capital), grows through networks (people and information), and produces entropy (waste and drift).

The investor’s job is to keep the system alive long enough for it to evolve into something more substantial. That means designing feedback loops, respecting natural limits, and recognizing that scaling is not just about getting bigger, but it is also about getting smarter.

Complexity Theory teaches that order and chaos are partners. Growth always produces tension. The best investors, like good scientists, don’t try to control every variable. They design simple rules and let self-organization take care of the rest.

Final Thoughts

Private equity is really about time—how we use it, manage it, and give it shape. Each phase of the lifecycle tests a different kind of intelligence:

- Imagination at the start

- Discipline in the first hundred days

- Resilience in the middle years

- Clarity at exit

Actual value creation is not about squeezing numbers. It is about building systems that keep learning.

When capital meets curiosity, when plans meet patience, and when leadership meets humility—companies don’t just grow, they evolve.

That is the art of private equity. It is about system building and transformation.

The Rise of AI Agents in Enterprise Architecture

Explores the blueprint for how AI agents will eventually become a layer of the enterprise stack, including roles, hierarchies, and error loops.

From Automation to Autonomy: The Next Enterprise Layer

In three decades of working with companies across SaaS, freight logistics, edtech, nonprofit, and professional IT services, I have seen firsthand how every operational breakthrough begins with a design choice. Early ERP implementations promised visibility. Cloud migration promised scale. Now, we enter a new phase where enterprises don’t just automate processes; they delegate judgment. The rise of autonomous AI agents, which are decision-making systems embedded within workflows, is forcing companies to confront a fundamental question: What does a self-steering enterprise look like?

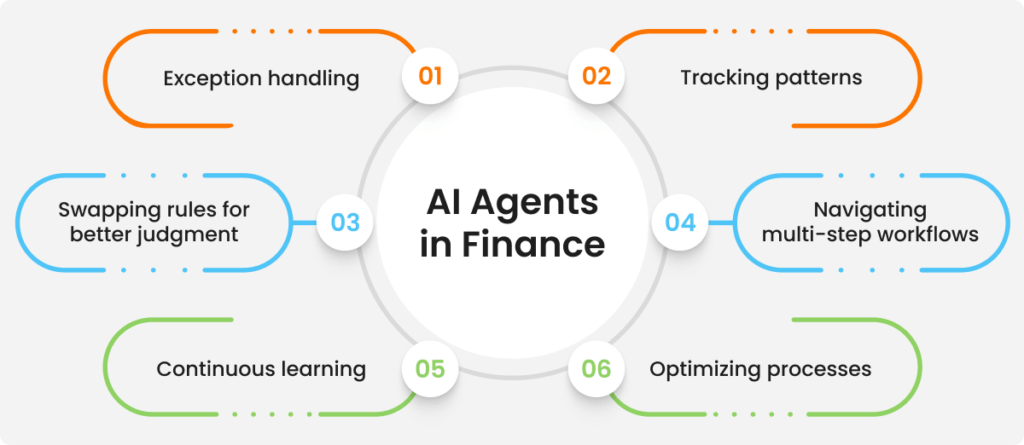

We are not talking about automation in the narrow sense of bots that click, sort, and file. We are referring to multi-agent systems that are autonomous entities trained to reason, escalate, and learn, and are embedded in revenue operations, compliance, finance, procurement, and even customer interaction. These agents do not merely follow logic trees. They operate with context. They perform functions that once required analysts, managers, and operations leads. They make decisions on your behalf.

The implications for enterprise design are profound. An architecture where humans and agents coexist must solve for hierarchy, interoperability, accountability, and trust. The autonomous enterprise will not emerge by stitching tools together. It will require a blueprint: a reimagination of systems, roles, and error recovery.

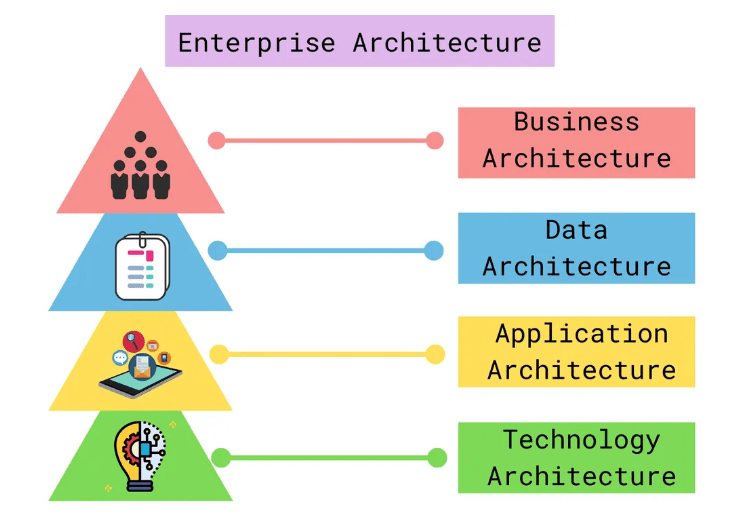

The AI Agent Stack: A New Operating System for Business

Just as companies once layered CRM on top of sales, or HRIS over people operations, we are now entering an era where AI agents form a cognitive layer across the enterprise. This layer does not replace ERP, CRM, or BI tools, but it orchestrates them.

In a Series C logistics company, the technology partner deployed a multi-agent system that monitored shipping costs, demand volatility, and SLA compliance. One agent forecasted volume. Another recommended pricing change. A third adjusted partner allocations based on reliability scores. None of these agents was isolated. They coordinated, negotiated, and escalated.

This layered system, what I now call the autonomous stack, includes four key components:

- Task Agents – Specialized agents designed for discrete workflows (forecasting, invoice reconciliation, contract flagging).

- Orchestration Agents – Meta-level agents that manage workflows across task agents, sequence dependencies, and ensure prioritization.

- Governance Agents – Watchdog systems that track agent behavior, decision logs, exception rates, and escalation patterns.

- Interface Agents – Agents that serve as the human-agent bridge, summarizing decisions, flagging anomalies, and allowing overrides.

The success of this architecture depends not just on model quality, but on how these agents interact, escalate, and recover. This is the true challenge of enterprise AI. Coordination, not capability, defines success.

Redefining Roles: From Managers to Model Supervisors

With agents taking over operational workflows, human roles must shift. The manager of tomorrow is not a task assigner. They are model supervisors: individuals who monitor agent behavior, fine-tune training data, review decision logs, and serve as an escalation point for unresolved ambiguities.

In a professional services firm, the CIO’s team deployed a time entry validation agent that cross-checked submitted hours against project charters and budget thresholds. Initially, the agent raised too many false flags. The team assigned a “controller”, a person trained in prompt design, logic validation, and pattern review. Within weeks, the number of false positives dropped by 60 percent. The agent learned. The controller’s role evolved into AI stewardship.

This is not a theoretical role. It is a design imperative. Every agent requires a human fallback path, a named individual or team who owns the domain, monitors behavior, and retrains the system when edge cases emerge.

Escalation Logic: Designing for Ambiguity

Autonomous systems thrive in structured environments. But ambiguity is a feature of enterprise life. A PO with mismatched terms, a billing dispute, a policy exception: all trigger the need for escalation. The best autonomous architecture does not suppress ambiguity. They design for it.

Each agent must be given confidence thresholds. When the confidence falls below a defined level, the agent escalates to a human, not with a question, but with a case file: data, context, options, and likely outcomes. The human then resolves and returns the resolution, which becomes new training data.

In an edtech firm, a finance agent reviews vendor payments. When faced with ambiguous tax classifications, it did not guess. It flagged the issue, explained the decision gap, and requested a policy update. Over time, this feedback loop reduced exception rates while improving policy precision.

Escalation is not a failure mode. It is a learning mode. When embedded into architecture, it becomes a source of resilience.

Trust and Transparency: Making the Invisible Visible

The most significant barrier to adoption in autonomous systems is not performance. It is opacity. Boards, CFOs, legal counsel, and frontline employees all ask the same question: How did the agent arrive at that decision?

The answer lies in decision traceability. Every autonomous agent must produce a log: inputs, model pathway, thresholds met, policies triggered, and the final action taken. These logs are not just for compliance; instead, they are for confidence.

In a compliance-heavy nonprofit, the autonomous grant review agent produced a “decision card” for every action. It listed the logic, risk flags, and supporting data. Reviewers could override or approve with a click. This created a culture of collaboration between humans and agents, not dependency or distrust.

Transparency is not a UI feature. It is an architectural principle. Trust compounds when systems explain themselves.

Error Loops and Systemic Recovery

All systems fail. The question is whether they recover intelligently. In autonomous enterprises, we must distinguish between local errors (a single agent failing to complete a task) and systemic errors (a cascade triggered by flawed agent assumptions).

This requires two safeguards:

- Autonomous monitoring agents – Designed to spot pattern anomalies, such as sudden drops in forecast accuracy or an increase in override frequency.

- Incident response playbooks – Predefined recovery paths that define when to roll back, retrain, or override models across the stack.

In a Series D SaaS company, a pricing optimization agent triggered an unexpected churn spike in a low-volume segment. The governance agent flagged an anomaly. The system auto-escalated. Human supervisors reviewed the pattern, adjusted the weighting of recent data, and retrained the model. The system self-healed within 48 hours. That agility is only possible when recovery is designed in advance.

Hierarchies of Intelligence: Flat Structure, Layered Control

Autonomous agents do not require hierarchy in the traditional sense. But they do require layered control. Orchestration agents must coordinate task agents. Governance agents must oversee orchestration. Interface agents must ensure humans stay in the loop.

This control plane enables a CFO, CRO, or COO to delegate with clarity. Not “let the machine decide,” but “let the system decide under these conditions, with this fallback, and with this visibility.”

We are not building a flat organization. We are building a layered intelligence architecture. And every layer must serve a different purpose: execution, synthesis, escalation, and communication.

From Workflows to Decision Flows

Most enterprise systems are designed around workflows, which are sequences of tasks that are completed by both systems and people. But autonomous enterprises operate on decision flows. The question becomes: What decisions are being made, by whom, with what confidence, and what outcome?

That is the CFO’s new visibility requirement. Not just “how long did the close take?” but “how many agent decisions were made, how many required escalation, and how many were corrected?”

In one multinational manufacturing organization, they tracked decision flow analytics and created a heatmap of friction points. It highlighted areas where agents struggled, where humans overrode too frequently, and where process ambiguity required design. That heatmap became their product roadmap.

Final Reflections: Designing With Responsibility

Autonomy is not a destination. It is a design choice. The companies that succeed will not be the ones that deploy the most agents. They will be the ones who design the clearest systems of accountability, oversight, and coordination.

We must build enterprises that not only scale output but also scale judgment. That not only eliminates work but also elevates insight.

The autonomous enterprise is not science fiction. It is already emerging: one agent at a time, one recovery loop at a time, and one design decision at a time.

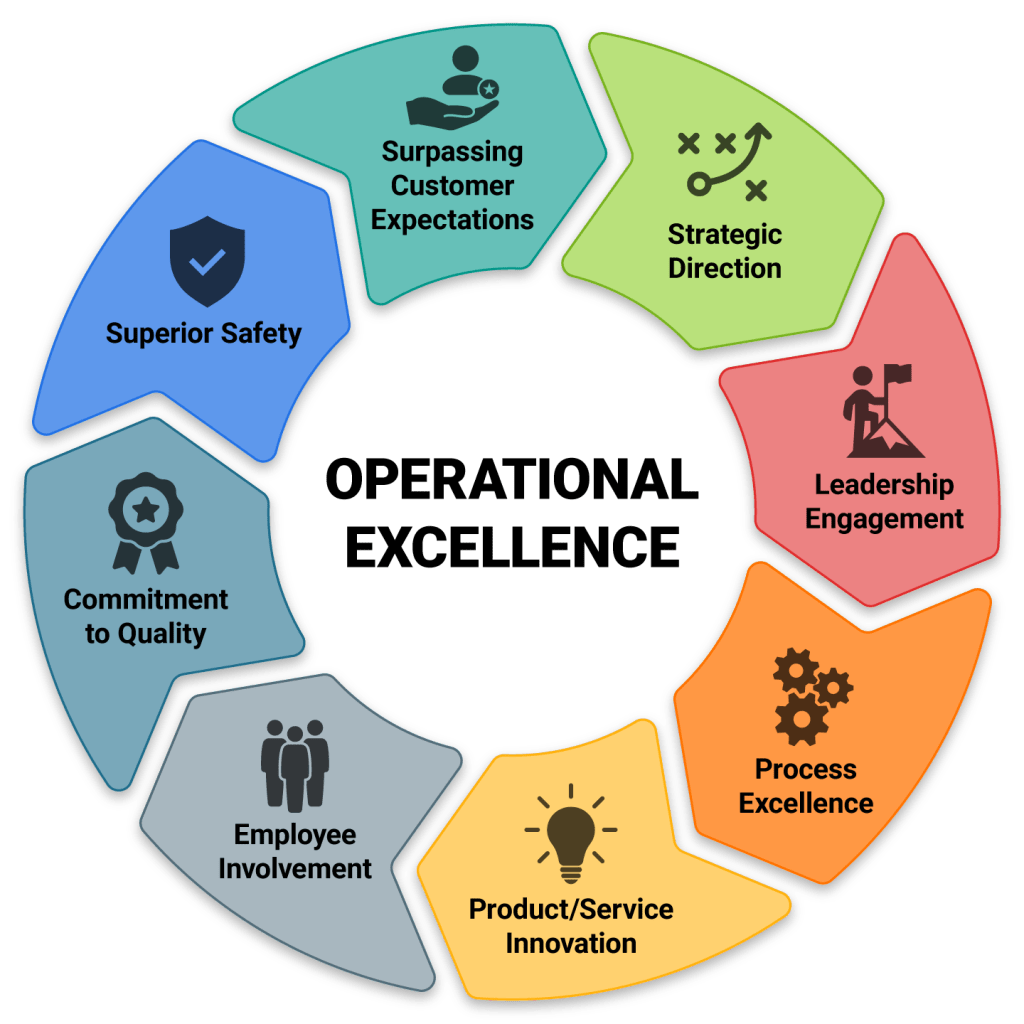

Operational Excellence: Drive Margin without Raising Prices

Finding Margin in the Middle: How to Drive Profit Without Price Hikes

In a market where inflation spooks buyers, competitors slash to gain share, and customers have more tools than ever to comparison-shop, raising prices is no longer the first, easiest, or even smartest lever to grow profit. Instead, margin must increasingly be found, not forced. And it must be found in the middle, which is generally found in the often-overlooked core of the operating model where process, precision, and practical finance intersect.

There is a reason why Warren Buffett often talks about companies with “pricing power.” He is right. But for most businesses, particularly in crowded or commoditized industries, pricing power is earned slowly and spent carefully. You cannot simply hike prices every quarter and expect customer loyalty or competitive positioning to stay intact. Eventually, elasticity catches up, and the top-line gains are eaten away by churn, discounting, or brand erosion.

So where does a wise CFO turn when pricing is off-limits?

They turn inward. They look beyond the sticker price and focus on margin mechanics. Margin mechanics refers to the intricate chain of operational, behavioral, and financial factors that, when optimized, deliver profitability gains without raising prices or compromising customer experience.

1. Customer and Product Segmentation

Not all revenue is created equal. Some customers consistently require more service, more concessions, or more overhead to maintain. Some products, while flashy, produce poor contribution margins due to complexity, customization, or low attach rates.

A margin-focused CFO builds a profitability heat map that resembles a matrix of customers, products, and channels, sorted not by revenue, but by gross margin and fully loaded cost to serve. Often, this surfaces surprising truths: the top-line star customer may be draining resources, while smaller customers yield quiet, repeatable profits.

Armed with this, finance leaders can:

- Encourage marketing and sales to prioritize “sweet spot” customers.

- Redirect promotions away from margin-dilutive SKUs.

- Discontinue or reprice long-tail products that erode EBITDA.

The magic is that no pricing change is needed. You’re optimizing mix, not increasing cost to the customer.

2. Revenue Operations Discipline

Most finance teams over-index on financial outcomes and under-index on how revenue is produced. Revenue is a function of lead quality, conversion rates, onboarding speed, renewal behavior, and account expansion.

Small inefficiencies compound. A two-week onboarding delay slows revenue recognition. A 5% lower renewal rate in one segment turns into millions in churn over time. A poorly targeted promotion draws in low-value users.

CFOs can work with revenue operations to improve:

- Sales velocity: Track sales cycle time and identify friction points.

- Sales productivity: Compare bookings per rep and subsequently adjust territory or quota strategies accordingly.

- Customer expansion paths: Analyze time-to-upgrade across cohorts and incentivize actions that accelerate it.

These are margin levers disguised as go-to-market metrics. Fixing them grows contribution margin without touching list prices.

3. Variable Cost Optimization

In many businesses, fixed costs are scrutinized with zeal, while variable costs sneak by unchallenged. But margin improvement often comes from managing the slope, not just the intercept.

Ask:

- Are your support costs scaling linearly with customer growth?

- Are third-party services like cloud, logistics, and payments growing faster than revenue?

- Are your service delivery models optimized for cost-to-serve by segment?

Consider the SaaS company that offers phone support to all users. By introducing tiered support, for example, live help for enterprises, self-serve for SMBs, it cuts the support cost per ticket by 30% and sees no drop in NPS. No price hike. Just better alignment between cost and value delivered.

There is an excellent YouTube video detailing how Zendesk transitioned to this model, which reduced costs, improved focus, and enabled smarter “land and expand” strategies for the GTM team.

4. Micro-Incentives and Behavioral Engineering

Margin lives in behavior. The way customers buy, the way employees discount, and the way usage unfolds are driven by incentives.

Take discounting. Sales reps often discount more than necessary, mainly out of fear of losing the deal or a reflexive habit of “close by any means possible”. Introduce approval workflows, better deal-scoring tools, and training on value-selling, and you will likely reduce unnecessary margin erosion.

Or consider customer behavior. A freemium product may cost more in support and infrastructure than it brings in downstream. By adjusting onboarding flows or nudging users into monetized tiers sooner, you reshape unit economics.

These are examples of behavioral engineering, which are minor design changes that improve how humans interact with your systems. The CFO can champion this by testing, measuring, and codifying what works. The cumulative effect on margin is real and repeatable.

5. Forecasting Cost-to-Serve with Precision

Finance teams often model revenue in detail but treat the cost of delivery as a fixed assumption. That is a mistake.

CFOs can partner with operations to build granular, dynamic models of cost-to-serve across customer segments, usage tiers, and service types. This enables:

- Proactive routing of low-margin segments to more efficient delivery models.

- Early warning on accounts that are becoming margin negative.

- Scenario modeling to test how changes in volume or behavior affect gross margin.

With this clarity, even pricing conversations become more strategic. You may not raise prices, but you may adjust packaging or terms to protect profitability.

6. Eliminating Internal Friction

Organizations bleed margins through internal friction due to manual processes, approval delays, redundant tools, and a lack of integration.

A CFO looking to expand margin without raising prices should conduct an internal friction audit:

- Where are we spending time, not just money?

- Which tools overlap?

- Which processes create avoidable delays or rework?

Every hour saved in collections, procurement approvals, and financial close contributes to margin by freeing up capacity and accelerating throughput. These gains are invisible to customers but visible on the profit and loss (P&L) statement.

7. Precision Budgeting and Cost Discipline

Finally, no discussion of margin is complete without cost control. But this is not about blanket cuts. It is about precision: the art and science of knowing which costs are truly variable, which drive ROI, and which can be deferred or restructured.

The CFO must move budgeting from a fixed annual ritual to a living process:

- Use rolling forecasts that adjust with real-time data.

- Tie spend approvals to milestone achievement, not just time.

- Benchmark cost centers against peers or past performance with clarity.

In this way, costs become not just something to report—but something to shape.

The Best Margin Is Invisible to the Customer

When you raise prices, customers notice. Sometimes they pay more. Sometimes they churn. However, when you achieve margin through operational excellence, behavioral discipline, and data-driven decisions, the customer remains none the wiser. And your business grows stronger without risking the front door.

This is the subtle, often-overlooked genius of modern financial leadership. Margin expansion is not always about dramatic decisions. It is about understanding where value is created, where it is lost, and how to gently nudge the machine toward higher efficiency, higher yield, and higher resilience.

Before calling a pricing meeting, consider holding a discovery session. Pull your data. Map your unit economics. Audit your funnel. Examine your cost structure. Trace your customer journey. Somewhere, there is a margin waiting to be found.

And it might just be the most profitable thing you do this year without changing a single price tag.

Transforming CFO Roles into Internal Venture Capitalists

I learned early in my career that capital is more than balance and flow. It is the spark that can ignite ambition or smother possibility. During my graduate studies in finance and accounting, I treated projects as linear investments with predictable returns. Yet, across decades in global operating and FP&A roles, I came to see that business is not linear. It progresses in phases, through experiments, serendipity, and choices that either accelerate or stall momentum. Along the way, I turned to literature that shaped my worldview. I grew familiar with Geoffrey West’s Scale, which taught me to see companies as complex adaptive systems. I devoured “The Balanced Scorecard ” and “Measure What Matters,” which helped me integrate strategy with execution. I studied Hayek, Mises, and Keynes, and found in their words the tension between freedom and structure that constantly shapes business decisions. In my recent academic detour into data analytics at Georgia Tech, I discovered the tools I needed to model ambiguity in a world where uncertainty is the norm.

This rich intellectual fabric informs my belief that finance must behave like an internal venture capitalist. The traditional role of the CFO often resembled a gatekeeper. We controlled capital, enforced discipline, and ensured compliance. But compliance alone does not drive growth. It manages risk. What the modern CFO must offer is structured exploration. We must fund bets, define guardrails, measure outcomes, and redeploy capital against the most successful experiments. And just as external investors sunset underperforming ventures, internal finance must have the courage to pull the plug on underwhelming initiatives, not as punishment, but as deliberate reallocation of attention and energy.

The internal-VC mindset positions finance at the intersection of strategy, data, and execution. It is not about checklists. It is about pattern recognition. It is not about spreadsheets. It is about framing. And it is not about silence. It is about active dialogue with product owners, marketers, sales leaders, analysts, engineers, and legal counsel. To be an internal venture capitalist requires two shifts. One is cognitive. We must see every budget allocation as a discrete business experiment with its own risk profile and value potential. The second shift is cultural. We must build circuits of accountability, learning, and decision velocity that match our capital cadence.

My journey toward this philosophy began when I realized that capital allocations in corporate settings often followed the path of least resistance. Teams that worked well together or those that asked loudly received priority. Others faded until the next planning cycle. That approach may work in stable environments. It fails gloriously in high-velocity, venture-backed companies. In those settings, experimentation must be systematic, not happenstance.

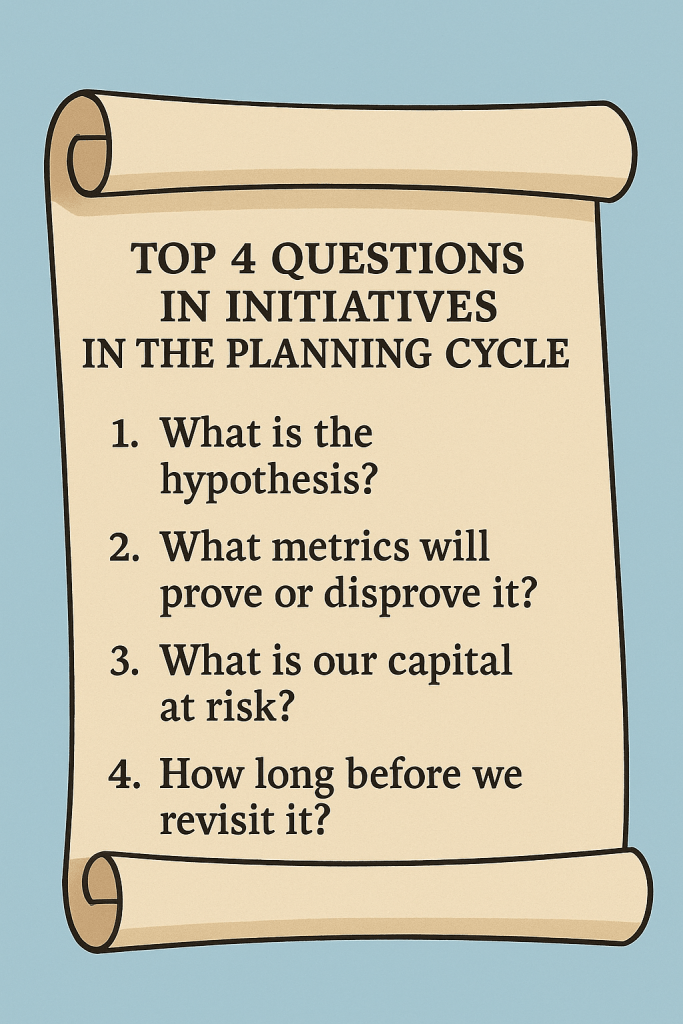

So I began building a simple framework with my FP&A teams. Every initiative, whether product expansion, marketing pilot, or infrastructure build, entered the planning process as an experiment.

We asked four questions: What is the hypothesis? What metrics will prove or disprove it? What is our capital at risk? And how long before we revisit it? We mandated a three-month trial period for most efforts. We developed minimal viable KPIs. We built lightweight dashboards that tracked progress. We used SQL and R to analyze early signals. We brought teams in for biweekly check-ins. Experiment status did not remain buried in a spreadsheet. We published it alongside pipeline metrics and cohort retention curves.

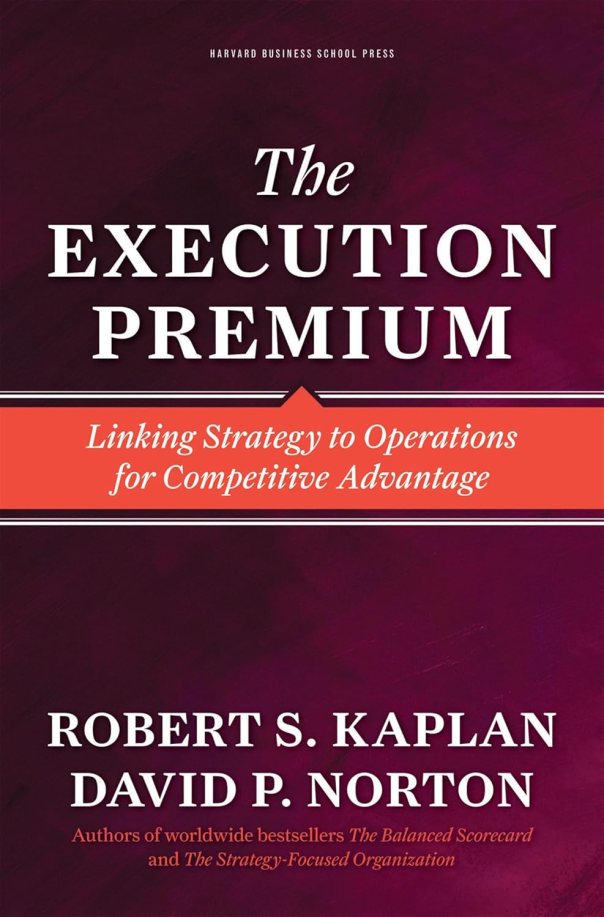

This framework aligned closely with ideas I first encountered in The Execution Premium. Strategy must connect to measurement. Measurement must connect to resource decisions. In external venture capital, the concept is straightforward: money flows to experiments that deliver results. In internal operations, we often treat capital as a product of the past. That must change. We must fund with intention. We must measure with rigor. We must learn at pace. And when experiments succeed, we scale decisively. When they fail, we reallocate quickly and intelligently.

One internal experiment I recently led involved launching a tiered pricing add-on. The sales team had anecdotal feedback from prospects. The product team wanted space to test. And finance wanted to ensure margin resilience. We framed this as a pilot rather than a formal release. We developed a compact P&L model that simulated the impact on gross margin, NRR sensitivity, and churn risk. We set a two-month runway and tracked usage and customer feedback in near real time. And when early metrics showed that a small segment of customers was willing to pay a premium without increasing churn, we doubled down and fast-tracked the feature build. It scaled within that quarter.

This success came from intentional framing, not luck. It came from seeing capital allocation as orchestration, not allotment. It came from embedding finance deep into decision cycles, not simply reviewing outputs. It came from funding quickly, measuring quickly, and adjusting even faster.

That is what finance as internal VC looks like. It does not rely on permission. It operates with purpose.

Among the books that shaped my thinking over the decades, Scale, The Balanced Scorecard, and Measure What Matters stood out. Scale taught me to look for leverage points in systems rather than single knobs. The Balanced Scorecard reminded me that value is multidimensional. Measure What Matters reinforced the importance of linking purpose with performance. Running experiments internally draws directly from those ideas, weaving systems thinking with strategic clarity and an outcome-oriented approach.

If you lead finance in a Series A, B, or C company, ask yourself whether your capital allocation process behaves like a venture cycle or a budgeting ritual. Do you fund pilots with measurable outcomes? Do you pause bets as easily as you greenlight them? Do you embed finance as an active participant in the design process, or simply as a rubber stamp after launch? If not, you risk becoming the bottleneck, not the catalyst.

As capital flows faster and expectations rise higher for Series A through D companies, finance must evolve from a back-office steward to an active internal investor. I recall leading a capital review where representatives from product, marketing, sales, and finance came together to evaluate eight pilot projects. Rather than default to “fund everything,” we applied simple criteria based on learnings from works like The Lean Startup and Thinking in Bets. We asked: If this fails, what will we learn? If this succeeds, what capabilities will scale? We funded three pilots, deferred two, and sunsetted one. The deferrals were not rejections. They were timely reflections grounded in probability and pragmatism.

That decision process felt unconventional initially. Leaders expect finance to compute budgets, not coach choices. But that shift in mindset unlocked several outcomes in short order. First, teams began designing their proposals around hypotheses rather than hope. Second, they began seeking metric alignment earlier. And third, they showed new respect for finance—and not because we held the purse strings, but because we invested intention and intellect, not just capital.

To sustain that shift, finance must build systems for experimentation. I came to rely on three pillars: capital scoring, cohort ROI tracking, and disciplined sunset discipline. Capital scoring means each initiative is evaluated based on risk, optionality, alignment with strategy, and time horizon. We assign a capital score and publish it alongside the ask. This forces teams to pause. It sparks dialogue.

Cohort ROI tracking means we treat internal initiatives like portfolio lines. We assign a unique identifier to every project and track KPIs by cohort over time. This allowed us to understand not only whether the experiment succeeded, but also which variables: segment, messaging, feature scope, or pricing-driven outcomes. That insight fashions future funding cycles.

Sunset discipline is the hardest. We built expiration triggers into every pitch. We set calendar checkpoints. If the metrics do not indicate forward progress, the initiative is terminated. Without that discipline, capital accumulates, and inertia settles. With it, capital remains fluid, and ambitious teams learn more quickly.

These operational tools combined culture and structure. They created a rhythm that felt venture-backed and venture-smart, not simply operational. They further closed the distance between finance and innovation.

At one point, the head of product slid into my office. He said, “I feel like we are running experiments at the speed of ideas, not red tape.” That validation meant everything. And it only happened because we chose to fund with parameters, not promote with promises.

But capital is not the sole currency. Information is equal currency. Finance must build metrics infrastructure to support internal VC behavior. We built a “value ledger” that connected capital flows to business outcomes. Each cohort linked capital expenditure to customer acquisition, cost-to-serve, renewal impact, and margin projection. We pulled data from Salesforce, usage logs, and billing systems—sometimes manually at first—into simple, weekly-updated dashboards. This visual proximity reduced friction. Task owners saw the impact of decisions across time, not just in retrospective QBRs.

I drew heavily on my analytics training at the Georgia Institute of Technology for this. I used R to run time series on revenue recognition patterns. I used Arena to model multi-cohort burn, headcount scaling, and feature adoption. These tools translated the capital hypothesis into numerical evidence. They didn’t require AI. They needed discipline and a systems perspective.

Embedded alongside metrics, we also built a learning ritual. Every quarter, we held a “portfolio learning day.” All teams presented successes, failures, surprises, and subsequent bets. Engineering leaders shared how deployment pipelines impacted adoption. Customer success directors shared early signs of account expansion. Sales leaders shared win-rate anomalies against cohort tags. Finance hosted, not policed. We shared capital insights, not criticism. Over time, the portfolio day became a highly coveted ritual, serving as a refresher on collective strategy and emergent learning.

The challenge we faced was calibration. Too few experiments meant growth moves slowly. Too many created confusion. We learned to apply portfolio theory: index some bets to the core engine, keep others as optional, and let a few be marginal breakers. Finance segmented investments into Core, Explore, and Disrupt categories and advised on allocation percentages. We didn’t fix the mix. We tracked it. We nudged, not decreed. That alignment created valuation uplift in board conversations where growth credibility is a key metric.

Legal and compliance leaders also gained trust through this process. We created templated pilot agreements that embedded sunset clauses and metrics triggers. We made sunset not an exit, but a transition into new funding or retirement. Legal colleagues appreciated that we reduced contract complexity and trimmed long-duration risk. That cross-functional design meant internal VC behavior did not strain governance, but it strengthened it.

By the time this framework matured at Series D, we no longer needed to refer to it as “internal VC.” It simply became the way we did business. We stopped asking permission. We tested and validated fast. We pulled ahead in execution while maintaining discipline. We did not escape uncertainty. We embraced it. We harnessed it through design.

Modern CFOs must ask themselves hard questions. Is your capital planning a calendar ritual or a feedback system? Do you treat projects as batch allocations or timed experiments? Do you bury failure or surface it as insight? If your answer flags inertia, you need to infuse finance with an internal VC mindset.

This approach also shapes FP&A culture. Analysts move from variance detectives to learning architects. They design evaluation logic, build experiment dashboards, facilitate retrospectives, and coach teams in framing hypotheses. They learn to act more like consultants, guiding experimentation rather than policing spreadsheets. That shift also motivates talent; problem solvers become designers of possibilities.

When I reflect on my intellectual journey, from the Austrian School’s view of market discovery to complexity theory’s paradox of order, I see finance as a creative, connective platform. It is not just about numbers. It is about the narrative woven between them. When the CFO can say “yes, if…” rather than “no,” the organization senses an invitation rather than a restriction. The invitation scales faster than any capital line.

That is the internal VC mission. That is the modern finance mandate. That is where capital becomes catalytic, where experiments drive compound impact, and where the business within the business propels enterprise-scale growth.

The internal VC experiment is ongoing. Even now, I refine the cadence of portfolio days. Even now, I question whether our scoring logic reflects real optionality. Even now, I sense a pattern in data and ask: What are we underfunding for future growth? CFOs who embrace internal VC behavior find themselves living at the liminal point between what is and what could be. That is both exhilarating and essential.

If this journey moves you, reflect on your own capital process. Where can you embed capital scoring, cohort tracking, and sunset discipline? Where can you shift finance from auditor to architect? Where can you help your teams see not just what they are building, but why it matters, how it connects, and what they must learn next?

I invite you to share those reflections with your network and to test one pilot in the next 30 days. Run it with capital allocation as a hypothesis, metrics as feedback, and finance as a partner. That single experiment may open the door to the next stage of your company’s growth.

Unveiling the Invisible Engine of Finance

Part I: Foundations of the Invisible Engine

I never wanted the spotlight. From my early days in finance, long before dashboards became fashionable and RevOps earned its acronym, I found joy in making complex systems work. I thrived in the silent cadence of reconciliations, the murmur of cross-functional debates over marginal cost assumptions, and the first moment a model finally converged. Unlike the sales team celebrating a quarter-end close or the product team announcing a roadmap win, the finance function rarely gets applause. But it moves the levers that make those moments possible.

Over three decades, I have learned that execution lives in the details and finance runs those details. Not with fanfare, but with discipline. We set hiring budgets months before a hiring surge begins. We write the logic trees that govern pricing behavior across regions. We translate long-range strategy into quarterly targets and daily prioritization frameworks. We forecast uncertainty, allocate capital, and define constraints, often before most stakeholders realize those constraints are the key to their success.

What I came to understand, and what books like The Execution Premium and the philosophies of Andy Grove and Jack Welch confirmed, was that finance does not just report performance. It quietly enables it. Behind every high-functioning Go-to-Market engine lies a financial scaffolding of predictive models, scenario assumptions, margin guardrails, and spend phasing. Without it, GTM becomes a series of disconnected sprints. With it, the organization earns compound momentum.

When I studied engineering management and supply chain systems, I began to appreciate the inherent lag in decision-making. Execution is not a sequence of isolated actions; it is a system of interdependent bets. You cannot plan hiring without demand signals. You cannot allocate pipeline coverage without confidence in product-market fit. And you cannot spend ahead of bookings unless your forecast engine tells you where the edge of safe investment lies. Finance is the only function that sees all those interlocks. We do not own the decision, but we build the boundaries within which good decisions happen.

This is where my training in information theory and systems thinking proved invaluable. Finance teams often drown in data. They mistake precision for insight. But not every number informs. I learned to ask: what reduces decision entropy? What signals help our executive team act more quickly with greater clarity? In an age where dashboards multiply daily, the finance function’s real job is to prioritize which visualizations matter, not to produce them all. A good forecast does not predict the future. It tells you which futures are worth preparing for.

Take hiring. Most people treat it as a headcount function. I see it as a vector of bet placement. When we authorized a 20 percent ramp in customer success headcount during a critical product launch, we did not do so because the spreadsheets said “green.” We modeled time-to-value thresholds, churn avoidance probabilities, and reference customer pipeline multipliers. We knew that delaying CSM ramp would cost us more in future expansion than it saved in current payroll. So we pulled forward the hiring curve. The team scaled. Revenue followed. Finance got no credit. But that was never the point.

In pricing, too, finance enables velocity. It is easy to believe pricing belongs solely to sales or product. But pricing without financial architecture is just an opinion. When we revamped our deal desk, we embedded margin thresholds not as hard stops, but as prompts for tradeoff conversations. If a seller wanted to discount below the floor, the system required a compensating upsell path or customer reference value. Finance did not say no. We asked, “What are you trading for this discount?” The deal desk transformed from a compliance gate to a business partner. It worked because we framed constraints as enablers—not limits, but levers.

Constraints often get misunderstood in early-stage companies. Founders want freedom. Boards want velocity. But constraints are not brakes; they are railings. They guide movement. I’ve seen companies chase too many markets too fast, hire too many reps without a pipeline, or build too much product without usage telemetry. Finance plays the role of orchestrator—not by saying “don’t,” but by asking “when,” “how much,” and “under what assumptions.” We stage bets. We create funding ladders. We model the downside—not to instill fear, but to earn permission to go faster with confidence.

These functions become more valuable as companies scale. A Series A company can live by intuition. By Series B, it needs structure. By Series C, it needs orchestration. And by Series D, it needs capital efficiency. At each stage, finance morphs from modeler, to strategist, to risk-adjusted investor. In one company, I helped define the bridge between finance and product through forecast-driven prioritization. Features did not get roadmap space until we modeled their revenue unlock path. The team resisted at first. But when they saw how each feature connected to pipeline expansion or customer lifetime value, product velocity improved. Not because we said “go,” but because we clarified why it mattered.

The teachings of Andy Grove always resonated here. His belief that “only the paranoid survive” aligns perfectly with financial discipline. Not paranoia for its own sake, but an obsessive focus on signal detection. When you build systems to catch weak signals early, you gain time. And time is the most underappreciated resource in high-growth execution. I recall one moment when our leading indicator for churn, a decline in logins per seat, triggered a dashboard alert. Our finance team, not success, flagged it first. We escalated. We intervened. We saved the account. Again, finance took no credit. But the system worked.

Jack Welch’s insistence on performance clarity shaped how I think about transparency. I believe every team should know not just whether they hit plan, but what financial model their work fits into. When a seller closes a deal, they should know the implied CAC, the modeled payback period, and the expansion probability. When a marketer launches a campaign, they should know not just the leads generated, but the contribution margin impact. Finance builds this clarity. We translate goals into economics. We make strategy measurable.

And yet, the irony remains. We rarely stand on stage. The engine stays invisible.

But perhaps that is the point. True performance systems don’t need constant validation. They hum in the background. They adapt. They enable. In my experience, the best finance organizations are not the ones that make the loudest noise, but they are the ones who design the best rails, the clearest dashboards, and the most thoughtful budget release triggers. They let the company move faster not because they permit it, but because they made it possible.

Part II: Execution in Motion

Execution does not begin with goals. It starts with alignment. Once the strategy sets direction, operations must translate intention into motion. Finance, often misconstrued as a control tower, acts more like a conductor, ensuring that timing, tempo, and resourcing harmonize across functional lines. In my experience with Series A through Series D companies, execution always breaks down not because people lack energy but because rhythm collapses. Finance preserves that rhythm.

RevOps, though a relatively recent formalization, has long been native to the thinking of any operational CFO. I have experienced the fragmented days when sales ops sat in isolation, marketing ran on instinct, and customer success tracked NPS with no tie to revenue forecasts. These silos cost more than inefficiency, they eroded trust. By embedding finance early into revenue operations, we gained coherence. Finance doesn’t need to own RevOps. But it must architect its boundaries. It must define the information flows that allow the CRO to see CAC payback, the CMO to see accurate pipeline attribution, and the CS lead to see retention’s capital impact.

One of the earliest systems I helped redesign was our quote-to-cash (QTC) pipeline. Initially, deal desk approvals were delayed. Pricing approvals were ad hoc. Order forms included exceptions with no financial logic. It was not malice, but it was momentum outrunning structure. We rebuild the process using core tenets from The Execution Premium: clarifying strategic outcomes, aligning initiatives, and continuously monitoring execution. Each approval step is mapped directly to a business rule: gross margin minimums, billing predictability, and legal risk thresholds. The system responded to the signal. A high-volume, low-risk customer triggered auto-approval. A multi-country deal with non-standard terms routed to a senior analyst with pre-built financial modeling templates. Execution accelerated not because we added steps but because we aligned incentives and made intelligence accessible.

I have long believed that systems should amplify judgment, not replace it. Our deal desk didn’t become fast because it went fully automated. It became fast because it surfaced the right tradeoffs at the right time to the right person. When a rep discounted beyond policy, the tool didn’t just flag it. It showed how that discount impacted CAC efficiency and expansion potential. Sales, empowered with context, often self-correct. We did not need vetoes. We needed shared logic.

Beyond QTC, I found that the most powerful but least appreciated place for finance is inside customer success. Most teams view CS as a post-sale cost center or retention enabler. I see it as an expansion engine. We began modeling churn not as a static risk but as a time-weighted probability. Our models, built in R and occasionally stress-tested in Arena simulations, tracked indicators like usage density, support escalation type, and stakeholder breadth. These were not metrics, but they were leading indicators of commercial health.

Once we had that model, finance did not sit back. We acted. We redefined CSM coverage ratios based on predicted dollar retention value. We prioritized accounts with latent expansion signals. We assigned executive sponsors to at-risk customers where the cost of churn exceeded two times the average upsell. These choices, while commercial in nature, had financial roots. We funded success teams not based on headcount formulas but on expected net revenue contribution. Over time, customer LTV rose. We never claimed the win. But we knew the role we played.

Legal and compliance often sit adjacent to finance, but in fast-growth companies, they need to co-conspire. I remember a debate over indemnity clauses in multi-tenant environments. The sales team wanted speed. Legal wanted coverage. We reframed the question: what’s the dollar impact of each clause in worst-case scenarios? Finance modeled the risk exposure, ran stress scenarios, and presented a range. With that data, legal softened. Sales moved. And our contracting process shortened by four days on average. It was not about removing risk, but it was about quantifying it, then negotiating knowingly. That is where finance shines.

When capital becomes scarce, as it inevitably does between Series B and Series D, execution becomes less about breadth and more about precision. The principles of The Execution Premium came into sharp focus then. Strategy becomes real only when mapped to a budget. We built rolling forecasts with scenario ranges. We tagged every major initiative with a strategic theme: new markets, platform expansion, cross-sell, and margin improvement. This tagging wasn’t for reporting. It was to ensure that when trade-offs emerged—and they always do—we had a decision rule embedded in financial logic.

One of my most memorable decisions involved delaying a product line expansion to preserve runway. Emotionally, the team felt confident in its success. However, our scenario tree, which assigned probabilities to outcomes, suggested a 40 percent chance of achieving the revenue needed within 18 months. Too risky. Instead, we doubled down on our core platform and built optionality into the paused initiative. When usage signals later exceeded the forecast, we reactivated. Execution didn’t slow. It sequenced. That difference came from finance-led clarity.

Jack Welch often spoke of candor and speed. I have found both thrive when finance curates a signal. We don’t have to own product roadmaps. But we can model the NPV of each feature. We don’t run SDR teams. But we can flag which segments produce a pipeline with the lowest acquisition friction. We don’t manage engineering sprints. But we can link backlog prioritization to commercial risk. Execution becomes not a matter of more effort, but of smarter effort.

As CFOs, we must resist the urge to be behind the curtain entirely. While invisibility enables trust, periodic presence reinforces relevance. I hold quarterly strategy ops syncs with cross-functional leaders. We don’t review P&Ls. We review the signal: what is changing, what bets are unfolding, and where are we off course? These sessions have become the nervous system of the organization. Not flashy. But vital.

The final piece is culture. Finance cannot enable execution in a vacuum. We must build a culture where trade-offs are discussed openly, where opportunity cost is understood, and where constraints are welcomed as tools. When a marketing leader asks for more spend, the best response is not “no.” It is, “Show me the comparative ROI between this and the stalled product launch acceleration.” When a CRO asks for higher quota relief, the correct answer is not “what’s budgeted?” It is “Let us simulate conversion ranges and capacity impact.” That is not gatekeeping. That is enabling performance with discipline.

To be an invisible engine requires humility. We do not win alone. But we make winning possible. The sales team celebrates the close. The board praises product velocity. The CEO narrates the vision. But behind every close, every roadmap shift, and every acceleration lies a decision framework, a financial model, a guardrail, or a constraint that is quietly designed by finance.

That is our role. And that is our impact.

From Noise to Signal: Optimizing Dashboard Utility in Business

Part I: From Data Dump to Strategic Signal

I have spent over three decades ( 1994 – present) watching dashboards bloom like wildflowers in spring, each prettier than the last, and many equally ephemeral. They promise insight but often serve as a distraction. I have seen companies paralyzed by reports, their leadership boards overwhelmed not by lack of data but by its glut. And as someone who has lived deep inside the engine room of operations, finance, and data systems, I have come to a simple conclusion: dashboards don’t win markets. Decisions do.

As a CFO, I understand the appeal. Dashboards give the impression of control. They are colorful, interactive, data-rich. They offer certainty in the face of chaos or at least the illusion of it. But over the years, I have also witnessed how they can mislead, obfuscate, or lull an executive team into misplaced confidence. I recall working with a sales organization that took pride in having “real-time dashboards” that tracked pipeline coverage, close velocity, and discount trends. Yet their forecast was consistently off. The dashboard was not wrong, but it was simply answering the wrong question. It told us what had happened, not what we should do next.

This distinction matters. Strategy is not about looking in the rearview mirror. It is about choosing the right path ahead under uncertainty. That requires a signal. Not more data. Not more KPIs. Just the proper insight, at the right moment, framed for action. The dashboard’s job is not to inform—it is to illuminate. It must help the executive team sift through complexity, separate signal from noise, and move with deliberate intent.

In my own practice, I have increasingly turned to systems thinking to guide how I design and use dashboards. A system is only as good as its feedback loops. If a dashboard creates no meaningful feedback, no learning, no adjustment, no new decision, then it is a display, not a system. This is where information theory, particularly the concept of entropy, becomes relevant. Data reduces entropy only when it reduces uncertainty about the following action. Otherwise, it merely adds friction. In too many organizations, dashboards serve as elegant friction.

We once ran a study internally to assess how many dashboards were used to change course mid-quarter. The answer was less than 10 percent. Most were reviewed, nodded at, and archived. I asked one of our regional sales leaders what he looked at before deciding to reassign pipeline resources. His answer was not the heat map dashboard. It was a Slack message from a CSE who noticed a churn signal. This anecdote reinforced a powerful lesson: humans still drive strategy. Dashboards should not replace conversation. They should sharpen it.

To that end, we began redesigning how we built and used dashboards. First, we changed the intent. Instead of building dashboards to summarize data, we built them to interrogate hypotheses. Every chart, table, or filter had to serve a strategic question. For example, “Which cohorts show leading indicators of expansion readiness?” or “Which deals exhibit signal decay within 15 days of proposal?” We abandoned vanity metrics. We discarded stacked bar charts with no decision relevance. And we stopped reporting on things we could not act on.

Next, we enforced context. Data without narrative is noise. Our dashboards always accompany written interpretation, which is usually a paragraph, sometimes a sentence, but never left to guesswork. We required teams to annotate what they believed the data was saying and what they would do about it. This small habit had a disproportionate impact. It turned dashboards from passive tools into active instruments of decision-making.

We also streamlined cadence. Not all metrics need to be watched in real time. Some benefit from a weekly review. Others require only quarterly inspection. We categorized our KPIs into daily operational, weekly tactical, and monthly strategic tiers. This allowed each dashboard to live in its appropriate temporal frame, and avoided the trap of watching slow-moving indicators obsessively, like staring at a tree to catch it growing.

A decisive shift occurred when we introduced a “signal strength” scoring to each dashboard component. This concept came directly from my background in information theory and data science. Each visualization was evaluated based on its historical ability to correlate with a meaningful outcome, such as renewal, upsell, margin improvement, or forecast accuracy. If a metric consistently failed to predict or guide a better decision, we removed it. We treated every dashboard tile like an employee. It had to earn its place.

This process revealed a surprising truth: many of our most beloved dashboards were aesthetically superior but strategically inert. They looked good but led nowhere. Meanwhile, the dashboards that surfaced the most valuable insights were often ugly, sparse, and narrowly focused. One dashboard, built on a simple SQL query, showed the lag time between proposal issuance and executive signature. When that lag exceeded 21 days, deal closure probability dropped below 30 percent. That insight helped us redesign our sales playbook around compression tactics in that window. No animation. No heat map. Just signal.

As our visualization maturity evolved, so too did our team’s confidence. We no longer needed to pretend that more data equaled a better strategy. We embraced the value of absence. If we lacked signal on a given issue, we acknowledged it. We deferred action. Or we sought better data, better modeling, better proxies. But we never confused motion with progress.

In my view, the CFO bears special responsibility here. Finance is the clearinghouse of data. Our teams sit closest to the systems, the models, the cross-functional glue. If we treat dashboards as reporting tools, that is how the organization will behave. But if we elevate them to strategy-shaping instruments, we change the company’s posture toward information itself. We teach teams to seek clarity, not comfort. We ask not what happened, but what it means. And we anchor every conversation in actionability.

I have often said that the most crucial question a CFO can ask of any dashboard is not “What does it show?” but “What would you do differently because of this?” If that answer is unclear, then the visualization has failed, no matter how real-time, colorful, or filterable it may be.

Part II: From Visuals to Velocity—Using Dashboards to Orchestrate Strategy

Let us now move beyond the philosophical and diagnostic into the orchestration and application of data in real business decisions. The CFO’s role as chaperone of insight comes into sharper relief not as a scorekeeper, but as a signal curator, strategic moderator, and velocity enabler.

As dashboards matured inside our company, we began to see their true power, not in their aesthetics or real-time updates, but in their ability to synchronize conversation and decision-making across multiple, disparate stakeholders. Dashboards that previously served the finance team alone became shared reference points between customer success, product, sales, and marketing. In this new role, the CFO was no longer the gatekeeper of numbers. Instead, the finance function became the steward of context. That shift changed everything.

Most board conversations begin with a review of the past. Revenue by line of business. Operating expenses against budget. Gross margin by cohort. And while these are useful, they often miss the core strategic debate. The board doesn’t need to relive the past. It needs to allocate attention, capital, and people toward what will move the needle next. This is where the CFO must assert the agenda, not by dominating the conversation, but by reframing it.

I began preparing board materials with fewer metrics and more signal. We replaced six pages of trend charts with two dashboards that showed “leverage points.” One visual highlighted accounts where both product adoption and NPS were rising, but expansion hadn’t yet been activated. Another showed pipeline velocity by segment, adjusted for marketing spend, which effectively surfaces which go-to-market investments produced yield under real-world noise. These dashboards weren’t just reports. They were springboards into strategy.

In one memorable session, a dashboard showing delayed ramp in a new region sparked a lively debate. Traditionally, we might have discussed headcount or quota performance. Instead, the visualization pointed toward a process gap in deal desk approvals. That insight reframed the problem—and the solution. We did not hire more sellers. We fixed the latency. This was not a lucky guess. It was the product of designing dashboards not to summarize activity, but to provoke action.

One of the critical ideas I championed during this evolution was the notion of “strategic bets.” Every quarter, we asked: what are the 3 to 5 non-obvious bets we are placing, and what leading indicators will tell us if they’re working? We linked these bets directly to our dashboards. If a bet was to scale customer-led growth in a new vertical, then the dashboard showed usage by that cohort, mapped to support ticket volume and upsell intent. If the bet was to expand our footprint in a region, the dashboard visualized cycle time, executive engagement, and partner productivity. These weren’t vanity metrics. They were wagers. Dashboards, in this model, became betting scorecards.

This way of thinking required finance to act differently. No longer could we assemble metrics after the fact. We had to co-design the bets with the business, ensure the data structures could support the indicators, and align incentives to reward learning especially when the bet didn’t pay off. In that context, the most valuable metric was not the one that confirmed success. It was the one that showed us we were wrong, early enough to pivot.

Internally, we began running quarterly “signal reviews.” These were not forecast meetings. They were sessions where each function presented its version of the signal. Product discussed feature adoption anomalies. Sales surfaced movement in deal structure or pricing pushback. Marketing shared behavior clustering from campaign performance. Each team showed dashboards, but more importantly, they translated those visuals into forward-looking decisions. Finance played the role of facilitator, connecting the dots.

One of the more powerful innovations during this phase came from a colleague in business intelligence, who introduced “decision velocity” as a KPI. It was not a system metric. It was an organizational behavior metric: how fast we decided from first signal appearance. We tracked time from the first indication of churn risk to action taken. We tracked lag from slow pipeline conversion to campaign change. This reshaped our dashboard design, which is making us ask not “What’s informative?” but “What helps us move?”

To manage scale, we adopted a layered visualization model. Executive dashboards showed outcome signals. Functional dashboards went deeper into diagnostic detail. Each dashboard had an owner. Each visual had a purpose. And we ruthlessly sunset any visualization that didn’t earn its keep. We no longer treated dashboards as permanent. They were tools, like code that is refactored, deprecated, sometimes rebuilt entirely.

The tools helped, but the mindset made the difference. In one planning cycle, we debated whether to enter a new adjacent market. Rather than modeling the full three-year forecast, we built an “option dashboard” showing market readiness indicators: inbound signal volume, competitor overlap, early adopter referenceability. The dashboard made the risk legible and the optionality visible. We greenlit a modest pilot with clear expansion thresholds. The dashboard didn’t make the decision. But it made the bet more intelligent.

Incentives followed. We restructured performance reviews to include “dashboard contribution” as a secondary metric, but not in the sense of building them, but in terms of whether someone’s decisions demonstrated the use of data, especially when counterintuitive. When a regional lead pulled forward hiring based on a sub-segment signal and proved correct, that was rewarded. When another leader ignored emerging churn flags despite visible dashboard cues, we did not scold, but we studied. Because every miss was a design opportunity.

This approach did not remove subjectivity. Nor did it make decision-making robotic. Quite the opposite. By using dashboards to surface ambiguity clearly, we created more honest debates. We didn’t pretend the data had all the answers. We used it to ask better questions. And we framed every dashboard not as a mirror, but as a lens.

A CFO who understands this becomes not just the keeper of truth, but the amplifier of motion. By chaperoning how dashboards are built, interpreted, and acted upon, finance can shift an entire company from metric compliance to strategic readiness. That, in my view, is the core of performance amplification. And it is how companies outlearn their competitors—not by having more data, but by making meaning faster.

The ultimate role of the CFO is not to defend ratios or explain variances. It is to shape where the company looks, what it sees, and how it decides. Dashboards are only the beginning. The real work lies in curating signal, orchestrating learning, and aligning incentives to reward decision quality, not just outcomes.

Markets reward companies that move with clarity, not just confidence. Dashboards alone can’t create that clarity. But a CFO who treats visualization as strategy infrastructure. And in the years ahead, those are the finance leaders who will reshape how companies navigate ambiguity, invest capital, and win markets.

The CFO’s Role in Cyber Risk Management

The modern finance function, once built on ledgers and guarded by policy, now lives almost entirely in code. Spreadsheets have become databases, vaults have become clouds, and the most sensitive truths of a corporation, like earnings, projections, controls, and compensation, exist less in file cabinets and more in digital atmospheres. With that transformation has come both immense power and a new kind of vulnerability. Finance, once secure in the idea that security was someone else’s concern, now finds itself at the frontlines of cyber risk.

This is not an abstraction. It is not the theoretical fear that lives in PowerPoint decks and tabletop exercises. It is the quiet, urgent reality that lives in every system login, every vendor integration, every data feed, and control point. Finance holds the keys to liquidity, to payroll, to treasury pipelines, to the very structure of internal trust. When cyber risk is real, it is financial risk. And when controls are breached, the numbers are not the only thing that shatter. You lose confidence, and the reputational risk is sticky.